There is no Christian revival

Hitching the British Right's wagons to Christianity would be a major error

There has recently been a great deal of noise about a supposed ‘quiet revival’ of Christian belief and practice, especially among the youth in Western countries. This began with Justin Brierley’s Surprising Rebirth of Belief in God. Published in 2023, Brierley argued, entirely anecdotally, that the conversation around faith had changed quite substantially over the past decade. Brierley, the host of a Christian radio show, pointed out that Jordan Peterson had replaced Richard Dawkins as the premier pop-philosopher of religion; atheism’s position of cultural dominance had receded.

At the time, this was a novel thesis which flew in the face of all the available statistical evidence, which had continually demonstrated that Christianity in Britain was on the decline. Earlier this year, however, Brierley found the statistical evidence that he had previously been lacking in the form of a Bible Society report entitled Quiet Revival. The report presented some rather striking claims, namely that church attendance was not only no longer in freefall, but had actually begun to rise, particularly among young men.

Many of those who engage in what Pimlico Journal has previously termed ‘the new theological politics’ have latched onto this apparent revival as a clear indicator that Christianity is destined to return as a major political force, and have used this to bolster existing arguments that faith ought to be a core part of our political identity moving forwards. They argue that the new right-wing movement that is emerging is a necessarily Christian movement, or at least that it should be if it wishes to succeed politically and in government.

We must urge caution. The evidence for this thesis remains limited. We have seen a few positive pieces of data, and heard a few anecdotes from individuals who, it should be noted, have built a media career on the back of the prospect of an imminent Christian revival. To build a political movement on such weak foundations seems deeply misguided, especially when the cause of these signals (even if they are not to be dismissed as mere noise) is as yet unclear. As with many recent statistics showing unusual trends, we believe there is a mostly unexamined factor behind the Christian renaissance: mass migration.

I do not discuss in this article whether a Christian Revival is itself a good thing or not (although, as a Christian myself, I think it is). Rather, I make two related points:

The existing data strongly suggests that, to the extent it does exist, the growth of Christianity in recent years is principally due to mass migration.

Due to these demographic realities, it would be unproductive for the new right to make Christianity a central part of its political identity.

The National Demographics of Christianity

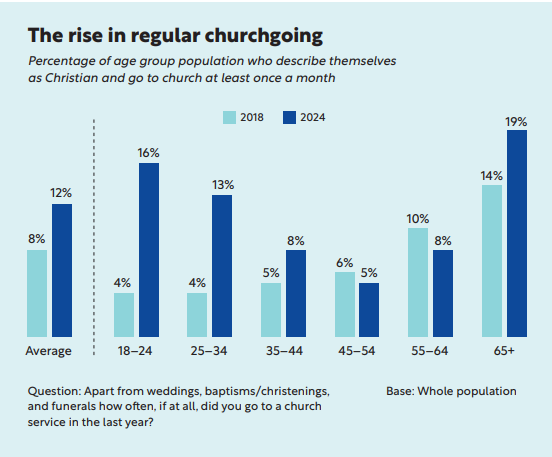

The primary evidence for the Christian revival comes from the aforementioned Bible Society study. The study compares two polls conducted on behalf of the Bible Society, one in 2018 and one in 2024. They find that in 2024, 16% of those aged between 18 and 24 identify as Christian and go to church at least once a month, compared to only 4% in 2018. There is an increase among all age groups and across both genders, though by far the most significant increase is for those aged between 18 and 24.

Helpfully, the Bible Society study directly addresses the question of ethnicity. They point out that 19% of churchgoers are ethnic minorities. This is roughly the same as Britain as a whole, suggesting that this ‘revival’ could not have been driven by immigration. But is this logic sound? We must remember that a significant proportion of the ethnic minorities in Britain are from countries that aren’t traditionally Christian (i.e., India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and China (inc. Hong Kong), all of which are in the top ten countries of origin for foreign-born UK residents). While one cannot rule out the possibility that a small number of immigrants from these countries will be from a Christian minority background, or may have converted to Christianity whilst in Britain, it is on balance safe to say that most will not be Christian.

Hence, we can assume that ethnicities that are traditionally Christian — mostly Africans and Afro-Caribbeans — are overrepresented in this statistic. This is illustrated by further evidence that the study provides: 47% of black people aged 18 to 34 attend church at least once monthly, compared to 18% for white people in the same age group. As such, whilst ethnic minorities in general are not overrepresented among churchgoers, those from Christian countries are — and substantially so.

We are beginning to paint a familiar picture for many regular church attendees: namely, that the two major groups in most churches are old white people and young (or at least younger) black people. When we control for age, these anecdotal observations are further validated by the statistics. The Bible Society study notes that when you observe only under-55s, fully 32% of churchgoers come from ethnic minority groups. According to the 2021 Census, 26% of the under-55 UK population is ethnic minority, with this percentage increasing dramatically as you look at younger and younger cohorts, making clear the effect that immigration would have on (say) the national statistics for the 18-24 grouping.

So young black people, and indeed black people in general, are far more likely to attend church than young white people. From this, it is no surprise to also learn that the churches experiencing the biggest growth are the Catholic Church and (especially) the Pentecostal Church, both denominations with stronger affiliation in the Third World than England’s ‘establishment’ Protestant denominations. It is likely no coincidence that the ‘Christian revival’ has coincided precisely with recent dramatic increases in immigration, especially considering the changing demographics of immigrants in recent years.

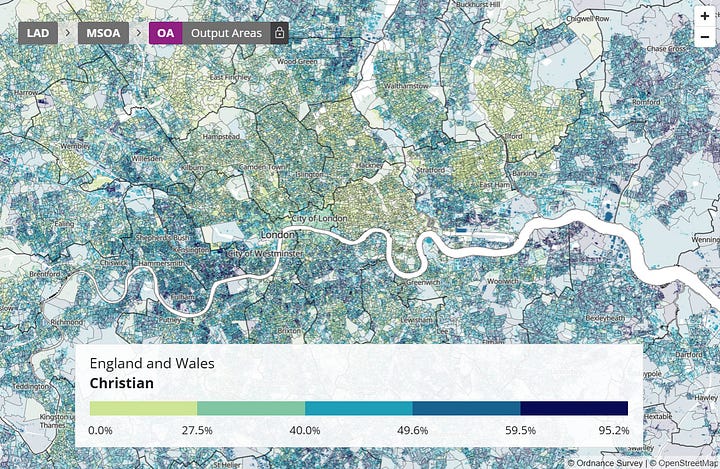

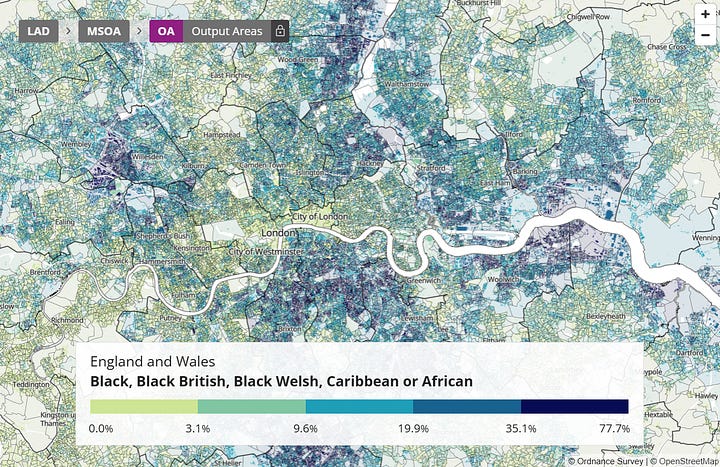

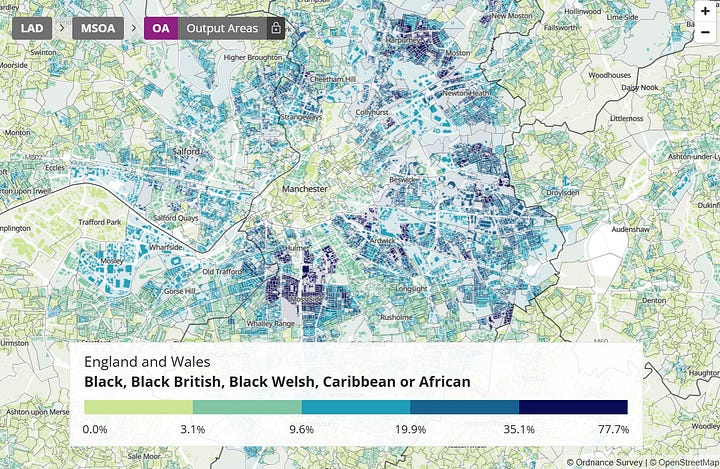

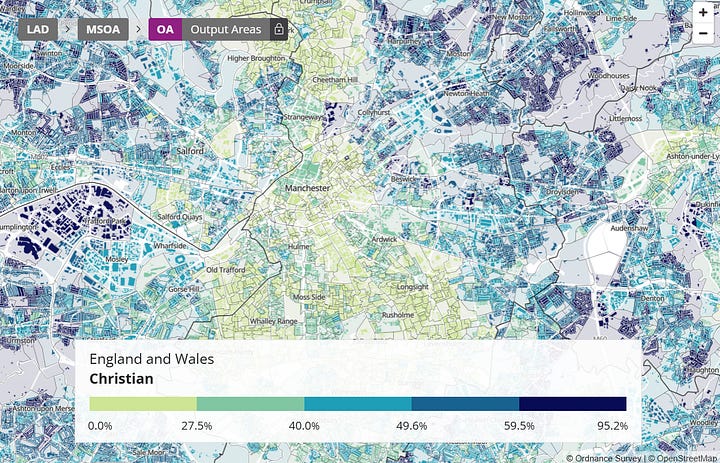

We can make a rough comparison of the demographic data provided by the ONS Census ourselves quite easily. Figures 1 and 2 show that many areas of London with higher proportions of Christians are also places with higher proportions of black people: for instance, Peckham, Camberwell, Thamesmead, Stratford, and Hackney.

On the other hand, Chelsea, Fulham, and Kensington are a clear exception here, since these areas seem comparatively white and also comparatively Christian. This can perhaps be explained by the unique demographics of such an area of London. Such an area is not seriously comparable to the rest of London, let alone the rest of the country. But other than this exception, there is otherwise an obvious correlation between people who identify as Christian and people who identify as black in London.

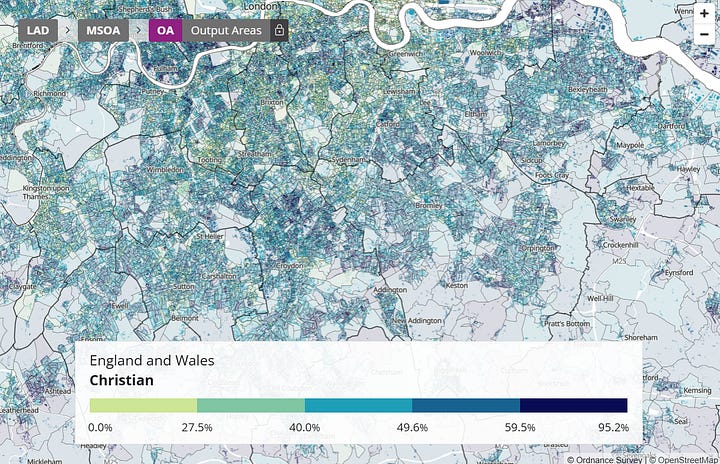

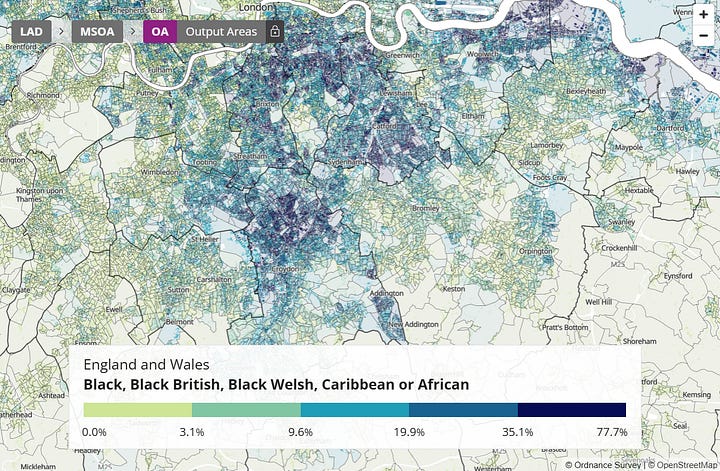

We can see a similar pattern if we look at South London (Figures 3 and 4). There are three major pockets where black people live in significantly higher amounts than the surrounding area in South London: the areas surrounding Peckham and Stockwell, the area surrounding Catford, and the area further south surrounding Broad Green and Thornton Heath. These areas also have higher proportions of people identifying as Christian than the less black areas nearby.

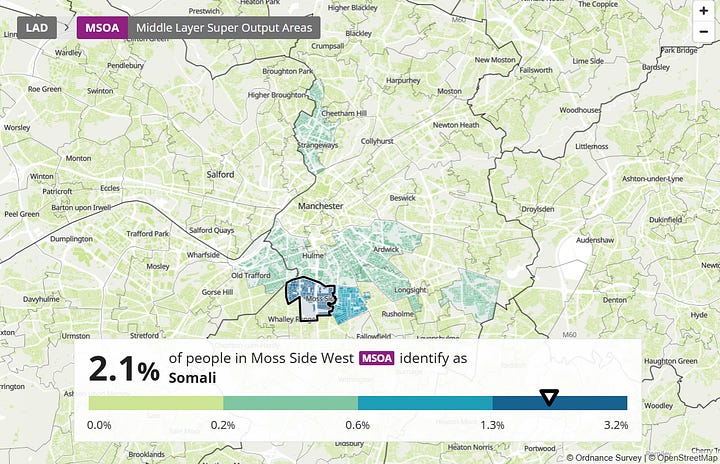

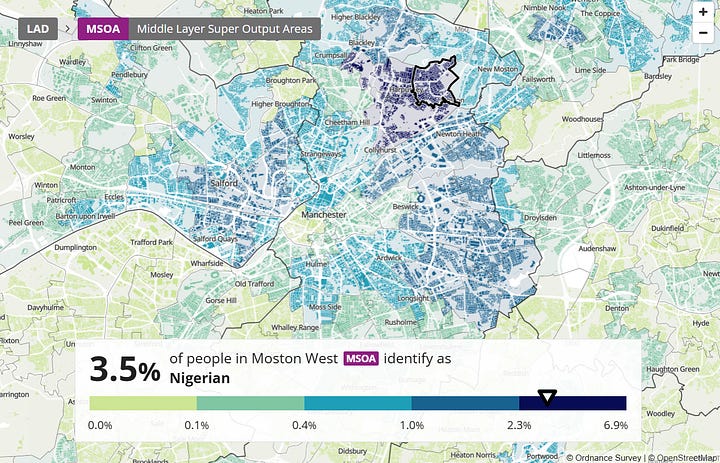

We can also look at Manchester (Figures 5 and 6). It may first look like an exception, as there seems to be a significant black community around Moss Side that does not practice Christianity at all. This exception, however, can be accounted for when we factor in national identity: Moss Side turns out to be a Somali community. We also find that those areas of Manchester with more West African, e.g. Nigerian (Figure 8), around East Manchester are more Christian than other areas.

This data is from 2021, before the ‘Boriswave’, and before there was any indication — and very little talk — of a ‘quiet revival’. But even then, we can see a moderate-to-strong geographical correlation between black identity and Christian identity. There will probably be an even stronger correlation now.

There are also other statistics that support this explanation. This UnHerd article points out that the least white census local authorities are associated with a smaller decrease in Christianity. The denominations with the most growth are generally newer and are more likely to be attended by black people. Furthermore, church openings are centred around areas that have higher immigrant populations.

We must also take into account a post-pandemic recovery in church attendance misleading many Christians. It certainly is the case that the past few years have seen a significant increase in Church attendance. However, if you look into data from both the Catholic Church and the Church of England (which produce reliable statistics because of their centralised structure), we find that church attendance is still below pre-pandemic levels. At the same time, the Bible Society reports that the proportion of practicing Christians who are Anglican has decreased (from 41% in 2018 to 34% in 2024) and the proportion who are Catholic has increased (from 23% to 31%) as well as Pentecostals (from 4% to 10%). A ‘revival’ this is not.

To make sense of the decreased church attendance since 2018 for both the Catholic and Anglican Church, while also taking into account the increasing proportion of the population attending church, including Catholic churches, we can provide the following explanation. Post-pandemic, a bigger proportion of people are attending non-Church of England protestant churches (such as Pentecostal churches) as well as Catholic churches. This is partly due to the fact that many of these people are new African immigrants who weren’t taken into account in the 2018 data, and partly because of converts to these charismatic Protestant and traditional Catholic denominations.

There is also a generational influence at work. Figure 9 is the table provided by the Bible Society study which shows the increase in proportion of the population who attend church monthly. As frequently, we can see the average has increased. It has also increased for every generation apart from 45-54 and 55-64, where it has actually decreased. A significant proportion of these people likely stopped attending during the pandemic and never returned. We can account for the decrease in numbers of people attending Catholic Churches while also explaining the increase in proportion by pointing out that roughly 30% of the population is aged between 45-64. If we calculate using the population data in 2018, we find that around 16.1 million people belong to this age group. If, for the sake of simplicity, we keep the 16.1 million number the same, a decrease in this age group represents a decrease in 235,000 people. Only 8% of the population are aged from 18-24,, or around 5.75 million people. An increase from 4% to 16% accounts for an increase of 690,000 people. Although there is such a great increase in the proportion of people aged 18-24 attending church, and only a small decrease in the 45-64 generation, the sheer scale of that generation leads to percentage changes having a greater impact on attendance than in the 18-24 generation. As such, much of the Christian revival will be reflected in proportions, but not necessarily in raw numbers (this is certainly the case with Catholicism).

It is also the case that the Anglican Church has seen a decrease in both proportion and numbers, with the Pentecostal Church seeing the opposite. These factors are mainly driven by an increasing religious apathy among those aged 45-64 as well as an increasing number of young people, many being African, attending mostly Pentecostal and Catholic churches (an article by HumanistsUK discusses this apparent divergence in statistics well).

This national demographic analysis demonstrates that the change in Christianity in Britain isn’t as simple as a ‘Christian revival’ and is closely linked to the increasing diversity among young people driven by immigration.

The Global Demographics of Christianity

The trends in Christianity’s demographic makeup globally provide further evidence of the direction Christianity in Britain is likely to take so long as current immigration policies remain in place. The Pew Research Centre points out that between 2010 and 2020, Sub-Saharan Africa surpassed Europe as the continent with the most Christians: in 2010, 25.8% of the world’s Christians lived in Europe and 24.8% lived in Sub-Saharan Africa; in 2020, 22.3% lived in Europe and 30.7% lived in Sub-Saharan Africa. This is a massive change.

It must also be understood that, although the proportion of the world’s population that is Christian is decreasing, the absolute number of Christians worldwide is still growing, having increased by 6% from 2010 to 2020. Although this pales in comparison to the increase in the number of Muslims (up 21%), Hindus (up 12%), and the religiously unaffiliated (up 17%), this is still a significant increase, and has been sufficient to ensure that Christianity remains the world’s largest religion by some distance.

When we look at that growth by region, the story becomes much clearer. The number of Christians has decreased in both North America (-11%) and Europe (-9%). This was offset by a big increase in Christians in Sub-Saharan Africa: an impressive 31%. (The numbers of Christians also grew in South America, Asia-Pacific, and MENA, but to a much lesser extent.) Sub-Saharan Africa is also the only world region where Christians grew as a proportion of the population; it even decreased in South America, which is widely thought of as the modern home of Catholicism, by 5%. Sub-Saharan Africa is therefore responsible for almost all the growth of Christianity in the world in the previous decade. We can assume that this will continue into the next decade as the population of Sub-Saharan Africa continues to explode.

This paints a clear picture of the demographic direction in which Christianity is going. It is quickly becoming a religion of the Third World — and especially Africa. These facts, plus the demographic findings of the Bible Society, should be more than enough proof to indicate that immigration, and particularly African immigration, is playing a major role in the ‘Christian revival’ both globally and, insofar as it exists, probably in this country also.

It is likely we will see the growth of Christianity speed up in the next few years as immigration continues; however, it is unlikely to ever reach the levels truly required to bring the global centre of the faith back closer to Europe and reverse the decrease in faith of the past decades. This is the case even when one does not account for age. According to the Bible Society, the age group with the highest proportion of practicing Christians is still over-65s. These people will not be around forever, and will leave many empty places on the pews that will need to be filled.

To see a genuine return to the biblically-informed culture of our past — an authentic revival of the British, and indeed European, Church — we would need to see a massive reconversion to Christianity across Europe by all generations, and in all likelihood an increase in the European population to offset the growing influence of Africans within the Church due to their own population boom. Short of that, the growth of Christianity represents not a ‘return’, but an importation of a tradition transmogrified by the changing demographic makeup of its adherents, both at home and abroad. If we discount the impact of immigration and look only at white conversions, we see that these are insignificant in comparison to what has occurred in the rest of the world since 2020. Christianity thus becomes less affiliated with European civilisation, and thus less affiliated with conventional right-wing goals; and although is is of course true that Christianity does not belong to any one national or ethnic group, from a political perspective (and we will discuss this further below), too closely associating Christianity with ‘right-wing’ causes is thus potentially dangerous.

None of this is to say that there is zero observable and significant social phenomenon of young white men converting to Christianity. The Bible Society study shows that this is probably the case. Furthermore, we cannot deny the anecdotal evidence, provided by both individuals and churches, of the many stories of such things occurring. However, what is also undeniable is that these statistics present a more complicated story than that of a simple return to the religion of our forefathers, and that a significant part of that story is a result of immigration.

If this is the case, why all the talk of the Christian Revival?

The idea of a great awakening among the English, a conversion as seen in the days of St Augustine of Canterbury’s mission, led by zealous young conservatives is certainly a pleasant narrative — especially for Christians. It exudes optimism; a kind of rallying cry that we are finally winning after a series of what seemed to be never-ending defeats at the hands of social liberalism. It tells us that attending Sunday Mass is a ‘Based’ act of political rebellion and collective action. It’s a nice story, and we can’t blame people for believing it.

I am of the view that the widespread belief in a popular, quiet revival of Christianity is mostly the result of an echo chamber of a very small class of highly-educated right-wingers in London and certain university towns (especially Oxford and Cambridge). These people, in turn, often succeed in influencing perceptions among rest of their broader social class and in the media. It is a social reality that people who are intelligent, often high-earning (or at least in high-prestige) jobs, highly politically interested, and graduates of prestigious universities all exist in the same circles in London. This is especially the case for the specifically British part of this cohort, given how international London is nowadays. Much like most other groups, this group also does not socialise much outside of their own circles (except perhaps when they go back to where they grew up, and often not even then). As such, much like any other group, they will often generalise about social trends within their class as if they are national trends.

It is likely that the ‘Christian revival’ is another example of one of these inaccurate generalisations to the national level. It does genuinely seem like there is a trend among the highly-educated, and especially highly-educated young men, towards Christianity. Many, even most, of the people reading this journal will be in such circles. Almost all of you will know of at least one person who has converted to Christianity, or revived their childhood faith, since 2020. For most white British people, however, especially in lower-educated areas, religion remains just as irrelevant as it always has been. Most church congregations outside of the few areas mentioned above are overwhelmingly elderly, and many of the new attendees will be immigrants.

Since there is a lot of anecdotal evidence deployed on the other side of this argument, I will now deploy some of my own. My hometown is Lincoln, and when I am back at home I go to a Catholic church there called St Hugh’s. I recently stayed in London for two weeks for work, and while I was in London, I attended the Brompton Oratory (also known as the London Oratory). I saw far more young white faces in the Oratory than I did at St Hugh’s, and saw far more young black faces in St Hugh’s than I did at the Oratory. This is despite Lincoln being around 92% white and 1.4% black, and London being around 36.8% white and 13.5% black. (It could be argued that Brompton Oratory, which is in Kensington and Chelsea, is located in a comparatively whiter part of London; the Oratory, however, is a famous church which Catholics from all over London travel to attend, so I do not think that this argument holds water.)

What does this mean for a right-wing Christian movement?

As mentioned, there has been a major push for the British Right to adopt a firmly ‘Christian conservative’ position on many policies and make Christianity a central part of the Right’s identity. Pimlico Journal has already pointed out on multiple occasions why this is a bad idea. Most of the country is no longer Christian. Socially conservative policies are at best a distraction, and at worst, through their general unpopularity, an active hindrance at a time when a right-wing victory has never been more urgent. Furthermore, it turns faith into a mere tool for achieving political, cultural, and social ends.

The demographic realities of Christianity both globally and in this country provide yet another reason for not pursuing this course. When a political movement decides what is central to its identity, it necessarily defines who belongs to that identity, and who doesn’t. The collapse of the Conservative Party and the seeming openness of Reform to the ideological influence of currents across the new right present a great opportunity to choose new principles to define our identity, and the identity of the nation as a whole, from the ground up. Choose wrong, and there may be big problems down the line.

If Christianity is made a central part of the new political movement, it will not only make the adoption of electorally unpopular policies more likely — it will inevitably lead to arguments in favour of immigration, which is the fundamental issue on which the new right-wing coalition in Britain is based. This will manifest in two ways. It will be argued that immigration of Christians is positive because it bolsters the influence of Christianity in Britain; and it will be claimed that anyone professing Christian faith will have no trouble becoming British: ‘After all, it’s a central part of our country’s identity.’ Although it is certainly possible for right-wing Christians to reject this argument, the temptation towards it is too strong to risk — as can be seen in Spain, where even the supposedly hard-right Vox party supports increased Latin American immigration on precisely those terms, and some American right-wingers have had the same attitude.

It is already clear that British Christians, even right-wing Christians, have found themselves easily swayed by the potential benefits of immigration to the British Church. We feel that our prayers have been answered by the empty pews being filled up through immigration. The British Church is now growing, and will continue to grow. Consequently, we frequently find British Christians voicing their support for immigration. Sometimes, this advocacy is straightforwardly left-wing and humanitarian; this is easy enough for the right-wingers to dismiss.

More difficult are those who make arguments specifically predicated on defending Christianity in this country. The Anglicans will tell us, ‘The Africans must come and save the Church of England.’ The Catholics will idealise the traditionalism of the Catholic Church in Africa: Cardinal Robert Sarah, for instance (notwithstanding Sarah’s own vocal criticisms of immigration into Europe, which are often conveniently ignored). Everyone on the Right will have heard defences of Nigerians or other Christian immigrant groups on the grounds of their allegedly socially conservative ‘values’.

The trouble with such a view is that it benefits the Church to the detriment of the nation. (It could further be added that such policies do not even benefit the global Church; they merely benefit certain national Churches by, in effect, shuffling Christians around the globe to plug holes in balance sheets, rather than actually creating more Christians and saving more souls.) From a Christian perspective, in an ideal society, the state and the Church should work together as the two administrative bodies of mankind. The role of the Church is spiritual governance, and the role of the state is governance for the sake of the prosperity of the citizenry. What is implicit in this view, and in the deliberate use of the term ‘citizen’, is that not everyone falls into that category. Nation-states are constructed over time by a uniquely constituted people; therefore, nation-states have special responsibilities to care for the prosperity of their own people. (Nation-states may also care for other people, but not to the outright detriment of the unique people who constitute the nation.) The Church has no such responsibility since it is universal.

The error that we are led towards by making Christianity a central part of our political movement’s identity — and therefore, our vision for a national identity — is assigning an element of universality to the citizenry of the nation. This comes at the detriment of who the state naturally ought to put first: the bona fide citizens of the nation. In the case of Britain, this means allowing mass migration from the Christian Third World for the universal ends of the church at the expense of the national ends of the British people.

This is a fundamental violation of the state’s duty towards the British people. A British Christian movement should care about ensuring more British people become Christian. It may see value in religious missions to convert people abroad, but it should not care about whether there are more Christians in Britain regardless of where they originally came from. Unconditional support for the Christian revival that comes at the cost of the long-term demographics of the nation and the prosperity of the British people will inevitably lead to such an error.

This is not mere political theorisation either. You can find a host of articles on UnHerd praising immigration’s effect on Christianity in Britain, as well as debating whether immigration restrictionism is compatible with Christian values. We don’t want these arguments to become mainstream and thereby slow down the momentum of the new political movement.

The existence of the Christian revival in Britain is, for the most part, a convincing illusion. Where a revival does exist, it is small; the dominant feature is immigration. Whether the Christian revival speeds up in the next few years and becomes a far more significant phenomenon, politically and otherwise, is still an open question. But what is clear that it would be a great strategic error for the British Right to make achieving a Christian revival central to its political identity, as this would lead us away from — and in many cases, actively subvert — our attempts to manage the most important issue of our time: demographic change.

This article was written by an anonymous Pimlico Journal contributor. Have a pitch? Send it to submissions@pimlicojournal.co.uk.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing. If you are already subscribed, why not upgrade to a paid subscription?

>The error that we are led towards by making Christianity a central part of our political movement’s identity — and therefore, our vision for a national identity — is assigning an element of universality to the citizenry of the nation.

I think you've hit nail on head. I think the central political objective of the British right should be to reject the logic of universalism wholesale.

As cliche as it is to quote De Maistre, I always have enjoyed this one (from Considerations on France):

“Now, there is no such thing as ‘man’ in this world. In my life I have seen Frenchmen, Italians, Russians, and so on. I even know, thanks to Montesquieu, that one can be Persian. But as for man, I declare I’ve never encountered him.”

My teen went through a phase of wanting a cross necklace and making the sign of the cross and saying "god bless" I'm pretty sure he was influenced mostly by his Syrian friend who makes a point of wearing a large cross on the outside of his shirt, but I have seen a surge in pro Christian TikToks.

The thing I noticed with his peers was a fad-like, superficial interest in Christianity (and Islam). Donning cross necklaces, putting cross in bio temporarily etc. But that's as far as it went. And it was more trendy last year and at the beginning of the year than it is now, and it's died down. Even become a bit cringe.

Through my son I'm familiar with a slightly older local lad (white, English) who is a bit of a TikTok personality who has become a Muslim but in a similarly surface level way e.g. saying "Inshallah" a lot and comparing non religious girls to good virgin girls (he is adamant he's getting a virgin Muslim girl though I doubt any with a brain will let their daughter near him) and performatively praying outside because it's time to pray now. He comes across as a lost working class soul, has a lot of ghetto mannerisms like walking with a hand down his trousers and makes those gang signs with his hands. My son thinks he's cool for now. For anyone who hasn't got teens or pre-teens they all say "Wallahi" atm, I nearly go insane from the amount of "wallahi bruv" I hear. But I also go insane from hearing about "big batty bunda" and rapping about drug dealing and stabbing people.

The Christian revival feels a little forced like a band-aid solution to the problems caused by mass migration and how it's changing us.

I'm increasingly suspicious when media personalities say Islam is the primary problem. It is a huge problem but to me it isn't the main one. The odd emergence of loads of Christians in media who have gone cuckoo with American style proclamations of Christ is King has, if anything, put me off Christianity. Are they all like this? It irritates me so intensely that I almost want to defend Muslims. They seem to think it's better to be ethnically mixed with African Christians than to protect an English non Christian demographic. If that's the case then the right needs to reconsider its alliances.

When I see things online like brown/black Christians or sikh "Christian allies" on the right take the piss out of English who are skeptical of a Christian revival or who are Muslim converts. It feels like someone is encroaching on my people and I really don't like it, even if I generally agree with the Christian. Again, it drives me away from Christianity. As do all of the "Thank God for Immigrants" posters.

My ultimate concern is that our homeland is being given away to foreigners and if we are atheist, Christian, Buddhist, pagan or whatever is secondary to that concern. But apparently not everyone feels that way and we must return to Christ the King in a multiracial orgy? It all feels very American.