Pints, prices, and the future of the pub

Will we lose the last of England?

Any right-minded Briton will be acutely aware of the price of a pint and, in particular, the seemingly never-ending rise of said price in recent years and the corresponding decline in numbers of Britain’s pubs. It was only after the lifting of Covid restrictions and the period of inflationary pressure that took hold following this that, for a number of reasons beyond the scope of this article, the emergence of a £6 pint in my affluent London drinking establishments began to emerge. I balked at it then and I still will only begrudgingly pay it now when required, even as £7 or, worse, £8 prices become more and more common.

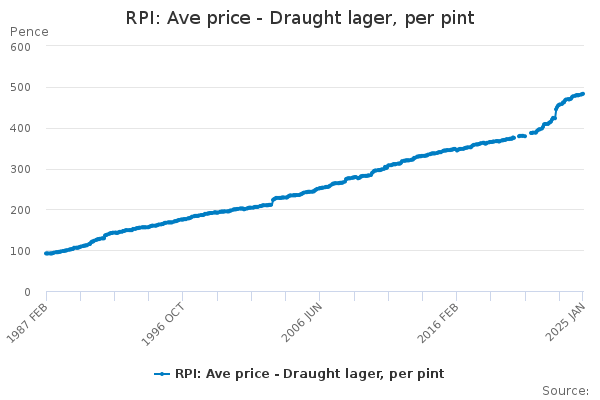

The price of a pint, as mapped by the ONS’s useful tool, has risen steadily over the decades and then, like many other price indicators in Britain, significantly and rapidly increased in the post-Pandemic period. These figures of course include pints across the length and breadth of the nation and account for the cheapest pints of low-rent lager in regional working men’s clubs and Wetherspoons as they do for the increasingly soulless pubs of central London and the ‘gastro’ hellholes of Clapham et al yuppy-burbia, but they nevertheless give a good overall picture.

In March 2020, the average price for a pint of draught lager stood at £3.75. By March 2022, this figure had surpassed the £4 mark and stood at £4.93 for January. It is quite likely that Britain has now passed the symbolic threshold of the £5 mark for a pint of lager being the average. This increase in price for a pint has not been accompanied by an increase in quality across Britain’s increasingly beleaguered drinking establishments. It is notable that it took over a decade for prices to move on average from the £3 to £4 mark, whereas we have likely seen the increase from £4 to £5 in little over three years.

While of course you can now find yourself paying over £7, or even as much as £8 if you happen to be in the wrong corporate- or tourist-focused watering hole, much of this rise in the average price of a pint is now most acutely felt outside of central London or other wealthy or touristic parts of the country. Prices that were in very recent memory the punchline of jokes about unaffordability of London are now the standard price for a pint in regional boozers, which have been suffocated by the unrelenting spiralling of costs — energy, labour, or business rates — affecting pubs across the country regardless of the wealth and property prices of the part of the country they operate in.

Many of these pressures are not new phenomena, partially explaining why more than a quarter of British pubs have closed since the year 2000, however these pressure have been exacerbated in recent years through the deliberate policy decisions of successive governments without meaningful understanding or regard of how policy, prices and the economy work in practice. This can of course be seen across the economy at large, as Chris Bayliss recently articulately described, but is in particular acutely felt by Britain’s pub trade.

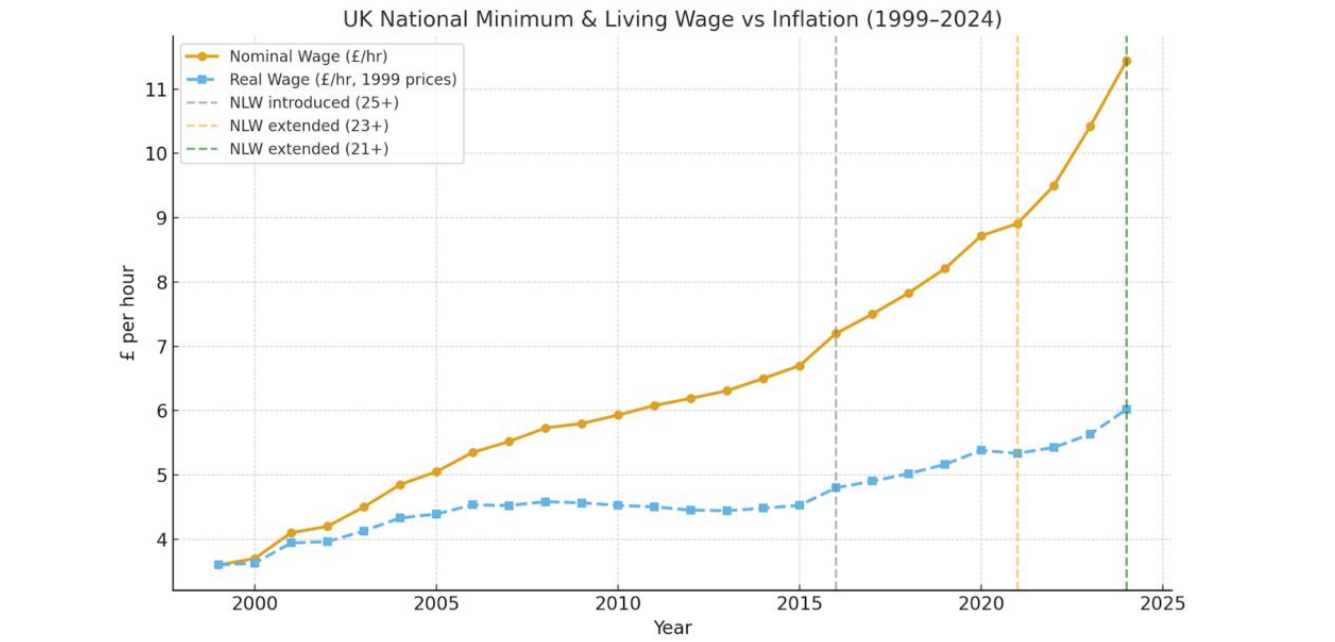

We now find ourselves in a position where the price of a pint in a well-appointed, touristy and generally desirable city centre pub is not that far ahead of what could be expected in rougher suburban or regional ‘proper boozer’. We have reached a point of pint price compression akin to the phenomenon of wage compression that many on the right have covered extensively in recent years and is one of the main sources of why many in Britain generally feel a lot poorer. The productivity busting rises of minimum wage in recent years have been a key source of both the wage and pint price compression problems that many will be knowingly or unknowingly familiar with.

Hospitality, and the pub trade in particular, has long paid the minimum wage for those carrying out the more basic and junior tasks in establishments but this would often be fine for the legions of students, young people and others looking for part time work. This is something I experienced in my own university years and the limited financial compensation was made up for by subsidised alcohol that went a long way. With the National Living Wage now standing at £12.21 an hour, and rising to £12.71 in April 2026, it is now a figure equivalent to around 66% of the salary of a median wage worker and is a significant factor in the rise of the price of a pint and the existential financial pressure that many pubs face. A solid rule of thumb that I have long operated is that pubs should aim to be able to offer at least their cheapest pint of lager at the equivalent of half an hour’s minimum wage work. Given this would now put that price at £6.10 and soon £6.35, it is no wonder that costs have skyrocketed across the board.

From experience, this pressure has been most felt in those pubs that have until recently done their upmost to resist price rises. On a recent visit to the Oxford Bar of Rebus fame in Edinburgh’s up market New Town, a pint of Scotland’s ubiquitous national lager Tennents set me back a seemingly reasonable £5.60 a pint. A trip to a less salubrious Edinburgh watering hole, the Anchor Inn in Granton that is best known for a well publicised gangland shooting instead of the scene of authors constructing their works of criminal fiction, saw the cash only bar charge around the £5 mark for a pint of Tennents. While of course anecdotal, it felt telling of the pressure that pubs across the board are facing in Britain.

Pubs have consistently been the primary losers of economic, social and policy changes in Britain in the last 30 years and their decline has mirrored and symbolised the changes that have taken place across the country in this period that have been well covered in this publication. The decline of the pub in Britain has been a great tragedy that marks a distinct break, largely enforced rather than voluntary, from our long and glorious history of enjoying beer in public environments.

This loss of meaningful third spaces in Britain, which for the vast majority of our recent history has been the pub, has had disastrous social consequences. It goes without saying that for older Britons, predominantly but not exclusively men in particular, the pub is a vital lifeline of social interaction and companionship and that the steep rise of prices, the shift to soulless ‘booze barns’ and indeed the closure of many neighbourhood locals greatly exacerbates the problem of old age loneliness. This also applies to many younger Britons who find themselves at the sharp end of the housing crisis that affects most facets of British life. As many readers of the publication will be acutely aware, young professionals living in London and elsewhere find themselves in flat or house shares with private space limited to an individual room, so the ability to enjoy communal spaces such as the pub is crucial and the decline of such establishments can track against the decline in quality of life for graduates and other young urban flat or house share dwellers. While nanny state public health bodies and their like may decry drinking as a great ill, the pub offers an unquantifiable but yet undeniable benefit to public wellbeing and happiness in Britain.

Of course, demographic change has played its part in the increasing pressure on and decline of Britain’s pubs in urban areas. Many ethnic minorities in Britain either do not drink at all or do so outside of the traditional pub environment. However, even in many of Britain’s most demographically transformed areas, pubs remain the last bastions for diminished communities that see such establishments as oases of their traditional identities. Indeed, from experience, many of London’s finest remaining ‘proper boozers’ can be found in areas that have seen the starkest change (readers would be highly recommended to enjoy a few cheap pints and a game of snooker in the Lord Stanely in Plaistow, even if the surrounding area might dampen spirits). While demographic change of course poses an existential long-term threat to the future of the pub in Britain, in recent years it has not been the sole catalyst for their closure

The next general election, almost certainly still quite some time off in 2029, already feels like it will be a defining election for British history at least on par with 1945, 1979 and 1997. While there are of course much more pressing and overarching issues in Britain that need addressing, any potential Reform government could do much worse than moving heaven and earth to support Britain’s pubs and in particular free houses to arrest their decline and disappearance across the country. Success would give a tangible sense of relief to a large swathe of the population that feels like their understanding of Britain has slipped away from them in recent years and is often most summed up by the closure of neighbourhood watering holes. The fight for the survival of the pub is the fight to preserve the very soul of Britain, as the pubs go so too does much of what we hold dear of this country. As Hilarie Belloc put it; “when you have lost your Inns drown your empty selves, for you will have lost the last of England.”

This article was written by an anonymous Pimlico Journal contributor. Have a pitch? Send it to submissions@pimlicojournal.co.uk.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing. If you are already subscribed, why not upgrade to a paid subscription?

Move to Yorkshire, drink Samuel Smiths Stout @£3.80, or Sam’s Organic Lager aka Rocket Fuel @£4.90………….or go for one of their cheaper beers and lagers- no phones, no laptops, no music, no TV’s, just humans chatting………

So well written. Loved the Belloc quote at the end.