Who are we? American Identity in the Age of Paper Americanism

From the founding until well within living memory, an 'American' was substantially defined by characteristics such as ancestry, culture, and religion

Commentators, politicos, and pundits disagree over what is or should be considered the defining issue of American public life in the twenty-first century. Foreign policy hawks might say it is the coming ‘shift to the Indo-Pacific’ to confront and deter an increasingly aggressive, expansionist China. Judges and lawyers might say it is declining public trust in traditional institutions. The more thoughtful of our intelligentsia might venture to suggest it is artificial intelligence, declining birth and marriage rates, or polarisation by class, education, or gender.

These and other issues certainly matter enormously in America and beyond, but they fall woefully short of pinpointing what should be, for those who have eyes to see, the obvious questions that matter most: What is America? and, extrapolating from that, What is an American? Those questions, though they may seem trite at first glance, are far deeper and more consequential.

Today, few people even bother asking those questions. Those who do give a range of unimaginative answers that betray either discomfort in seriously engaging with the questions or a lack of interest in doing so. Liberals might say that America is a ‘democracy’ or a ‘liberal democracy’, and that an American is someone who subscribes to those political systems. They are especially fond of the post-1945 — and especially post-’60s — mythology of America as a ‘melting pot’ (a widely-misunderstood term in its own right) and a ‘nation of immigrants’. Some more glib liberals might define an American as anyone who the federal government decides to grant citizenship to, or as only the indigenous occupiers of the landmass that became the United States.

Conservatives — who in America are often simply yesterday’s liberals, classical or otherwise, but that discussion is for another essay — at least have an instinctive reverence for their country and her founders and history, but give the matter a little more thought. They might say that America is a ‘constitutional republic, NOT a democracy’ (this distinction between a ‘democracy’ and a ‘republic’ nowadays being an almost uniquely American argumentation), but also that she is unique among the countries of the world as a ‘credal’ or ‘propositional’ nation to which anyone who adopts and espouses the founding principles can belong to as surely as the descendants of the original English settlers of Jamestown in 1607 or Plymouth Rock in 1620.

The conservatives often do not seem to consider whether the cultural proximity of prospective immigrants to historical American culture, expectations, religion, and values is a factor in whether or not they will be able to successfully assimilate upon arrival here. Both camps generally take it for granted that America — in theory and properly understood — is defined by difference, diversity, pluralism, tolerance, and the ability for people completely different from one another in all of the ways traditionally used to define common nationhood to live relatively harmoniously together under equal laws and shared political institutions. In other words, it is moderate in contemporary America to take the historically radical position that our common nationhood is defined because of, not in spite of, what makes us different from one another.

Recent American conservatives such as Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush articulated as much. In his final speech as president, Reagan endorsed a quotation from a letter he received:

You can go to live in France, but you cannot become a Frenchman. You can go to live in Germany or Turkey or Japan, but you cannot become a German, a Turk, or a Japanese. But anyone, from any corner of the Earth, can come to live in America and become an American.

Reagan practiced what he preached. He signed into law the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, which granted amnesty to most illegal aliens present in the United States before January 1 of that year. George H.W. Bush, Reagan’s vice president and successor, did likewise. Through the Immigration Act of 1990, he drastically increased the number of legal immigrants accepted annually, and established America’s Diversity Immigrant Visa which, somewhat perversely, admits a certain number of immigrants annually quite literally on the basis of how culturally distant their home country is from the historical understanding of what it meant to be an American. A few other Anglophone countries have points-based visa systems, but America’s diversity lottery is unique in the world. Instead of ‘blood and soil’, it is taken for granted that to become a true American indistinguishable from any other one must essentially merely express a desire to adopt liberal modern pluralism and ‘get a job, play by the rules, and work hard’.

Now, perhaps this universal Americanism — what one might call ‘Paper Americanism’ — is the correct view today. Maybe it represents the creed of an enlightened nation willingly unshackled from Old World nuisances such as ethnic conflict or wars of religion, trading benighted prejudices for idealised, tolerant humanism. I do not write this essay to argue that Paper Americanism is necessarily ‘wrong’. Rather, I intend to demonstrate that it is clearly at odds with the historical reality of what the terms ‘America’ and ‘American’ connoted until very recently, and that if that reality is not grappled with and a sufficient alternative for what those terms mean today not proffered, the country’s social fabric will continue to disintegrate as more and more newcomers continue to dispense with the pretence of assimilation and act as transplants from their country of origin relocated to a new environment where they can practice their ancestral lifestyle while enjoying a first-world standard of living while it lasts.

After all, if anyone can become an American and America is defined by her ability to host people completely different from one another, why, for example, should an Indian or a Somali man not simply remain an Indian and a Somalian on American soil?

Reagan and Bush can be somewhat forgiven for not having the foresight to anticipate where their Paper Americanism would logically lead today. After all, they governed a triumphant country that was still basically recognisable as the one in which their ancestors built the transcontinental railroad, fought the Civil War, settled the west, and was defeating (or at least outlasting) Soviet communism. Today, the situation is very different. Catholicism is now the biggest Christian denomination. Hispanics are now at least a quarter of the population if one believes any but the most conservative estimates of the illegal immigrant population. The Asian population is rapidly growing, as is their disproportionate representation in elite institutions. The foreign-born share of the population is about 20%. Members of all of those groups have contributed positively to the country in various ways. But the fact is that those and other such trends — such as the decline in family formation and religious belief — have rendered the country practically unrecognisable to the one well within living memory that was aligned with the historical understanding of American identity.

Various authors have analysed historical American identity or explored the emerging identity crisis. In Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America (1989), for example, David Hackett Fischer makes the case that, at least at one point, America was as much a people as she was an idea, and that even those who later arrived of non-Anglo-Protestant ethnic backgrounds adopted and preserved the cultural folkways left behind by the original settlers. In essence, he argues that ‘pre-diversity’ America can in fact be divided into four distinct Anglo-Protestant ethnocultural folkways. For example, the so-called ‘Cavaliers’ of the South came by way of the South of England. Many of the Cavaliers were descended from younger sons of noble families who, as Royalist supporters of King Charles I, were displaced after the Puritans’ victory in the English Civil War. Over the next twenty-five years or so, the Cavaliers settled the Virginia Tidewater region and later the Carolinas and Georgia. They gave the American South the characteristics that always defined it: Anglicanism, aristocratic values centered on hierarchy and paternalism, rigid senses of deference and honour, and, yes, an agrarian economy then heavily reliant upon the labour of indentured servants and the evil of the transatlantic slave trade.

By contrast, those Fischer calls the Borderers, but who are more commonly referred to in America as Scots-Irish, originated in the borderlands between England and Scotland and, later, Ulster. They began settling the Appalachian backcountry between about 1717-1775 before eventually spreading into the Deep South and West. Predominantly Presbyterian, the Scots-Irish embraced a tough, survivalist ethos that cherished individual liberty while combining uncompromising loyalty to family and kin with suspicion of outsiders. Through their anti-establishment, populist politics and instinctive opposition to change, the distinctive Scots-Irish American echoes to this day.

Fischer’s history of the Cavaliers and the Scots-Irish strongly suggests that American identity, from long before the founding up until quite recently, was never grounded solely in abstract principles; instead, it was deeply shaped by culture, regional character, and tradition. It was, fundamentally, formed by specific people, with specific characteristics. They, and the other groups identified by Fischer, did not make America simply by being immigrants, or people who happened to move from one place to another. What was far more important was who they were, where they moved from, why they moved to where they did, and what they did upon their arrival.

The late Samuel P. Huntington also examined American identity in his treatise Who Are We? The Challenges to American Identity (2004). Huntington challenges the modern notion of America as a ‘nation of immigrants’, instead arguing that the country is, or was, better understood as an Anglo-Protestant ‘nation of settlers’. Writing at the turn of the century as globalism chipped away at the American ability to maintain its particular parochial national identity and the Hispanic minority was growing exponentially, Huntington argued that Anglo-Protestant culture, ‘…its language, its civic ideals and habits, its individualism, its work ethic… shaped the national identity of a unique kind of nation.’

The situation in America today calls to mind the thought experiment of the Ship of Theseus. If a critical mass of ‘Americans’ do not speak English natively, is America still American? If they lack the American work ethic and our zeal for commerce and private property rights? If they forsake the American love for limited government and self-reliance with ethnic voting blocs, nepotism, and welfarism? If they turn away from the Christian faith that animated the American experiment in favour of foreign religions or secularism? Huntington does not profess to know precisely how to parse all of this, and indeed he was a Democrat quick to acknowledge the importance of immigration (with rigorous assimilation) to American national development, but he acknowledges the need for Americans to seriously consider what it means to be one and what will hold us together if and when Paper Americanism proves too fragile a bond.

But even more compelling than recent scholarship are the actual words of American jurists, settlers, and statesmen from the colonial and founding eras through the early republic right up to the inflection point of the ’60s. In her charter to Sir Walter Raleigh to begin the colonisation of Virginia (1584), Queen Elizabeth I could not have been clearer in her desire to see the seed of an Anglo-Protestant polity successfully planted in American soil:

…graunt to our trustie and welbeloued seruant Walter Ralegh… to discover… barbarous lands… not actually possessed of any Christian Prince, nor inhabited by Christian People… it shal be necessary for the safetie of al men … to line together in Christian peace… ordinances… agreeable to the forme of the lawes, statutes, governement, or pollicie of England, and also so as they be not against the true Christian faith, nowe professed in the Church of England.

The Pilgrims of Plymouth Rock had similar ideals in the first governing charter of Plymouth Colony, the Mayflower Compact (1620). In the name of God and King James I of England, they pledged to form a ‘…civil Body Politick, for our better Ordering and Preservation.’ On the tricentennial of the compact’s signing in 1920, President Calvin Coolidge acclaimed the document as the ‘foundation of liberty based on law and order’ in keeping with the Anglo-American tradition of democratic self-government contingent upon an intergenerational covenant of duties and obligations.

The Founding Fathers declared American independence from Great Britain. But in doing so, they sought to preserve and perfect their Anglo-American heritage. The founders were not, as is too often supposed today, an intellectual or philosophical monolith. They disagreed strenuously amongst themselves. Debates included those over the ratification and worthiness of the Constitution, and Thomas Jefferson’s (agrarian republic of virtuous yeoman farmers) and Alexander Hamilton’s (financial and industrial titan with a paternalistic elite) competing visions of the American future. But despite these differences, virtually all of the founders would have found the idea that America could or should ever not be a fundamentally Anglo-Protestant nation utterly ludicrous.

John Jay, Founding Father and first Chief Justice of the United States, certainly would have. In Federalist No. 2, discussing the threat of foreign influence to the fledgling republic, expressed his thanks that:

Providence has been pleased to give this one connected country to one united people—a people descended from the same ancestors, speaking the same language, professing the same religion, attached to the same principles of government, very similar in their manners and customs, and who, by their joint counsels, arms, and efforts, fighting side by side throughout a long and bloody war, have nobly established general liberty and independence.

Jay did not seem to think his generation founded a nation based purely on abstract principles with zero reference to ‘blood and soil’. Nor did the legislators of the 1st United States Congress, who defined eligibility for naturalized citizenship to include only ‘free white person(s)... of good character’ in the Naturalization Act of 1790. Judicial interpretation of that and later similar laws upheld this sentiment well into the twentieth century. In Ozawa v. United States (1922) and United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind (1923), the court held, for example, that Japanese and Indians were not eligible for naturalization. A lower court in Michigan ruled similarly with regard to Arab Muslims in In Re Ahmed Hassan (1942).

Again, this essay should not be construed as arguing that any of those laws or rulings were necessarily appropriate or moral; indeed, in certain cases they were clearly not. The founders obviously acted immorally by defining eligibility for naturalised citizenship on the basis of skin colour. Those subsequent classifications and rulings are — at best — deeply distasteful to modern sensibilities, and once again, there is no doubt that many members of all of those and other groups have contributed greatly to the United States. The point is that for all of American history until well within living memory, the common understanding of American identity had components traditional to notions of nationhood throughout world history: ancestry, culture, customs, ethnicity, race, religion. Perhaps early Americans were wrong to use those default human measurements of nationhood and are now pioneers in pluralist utopianism — but they unquestionably did.

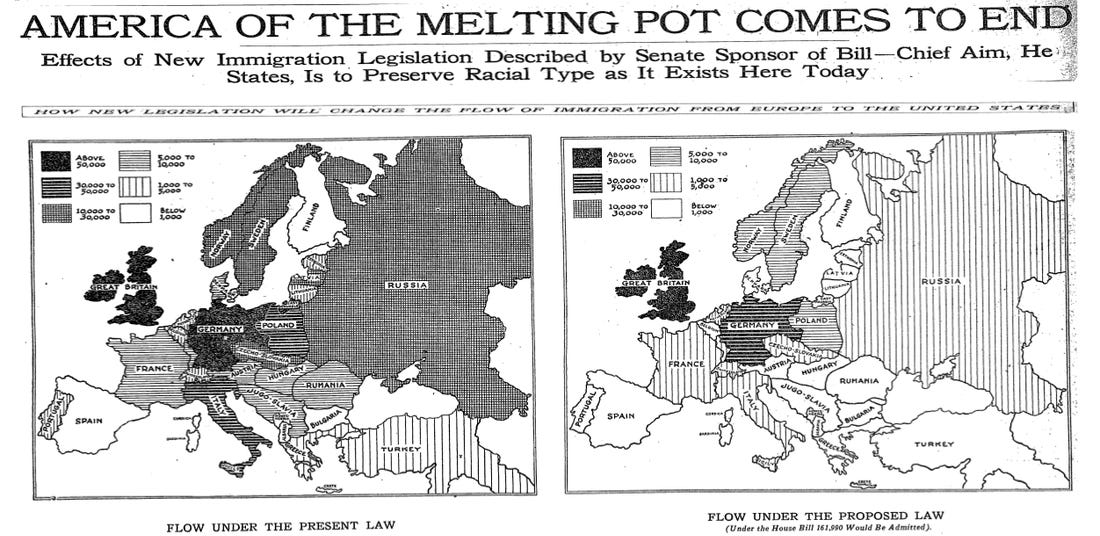

The rapid, unaccounted for definitional shift in what the terms ‘America’ and ‘American’ connote can be best understood through two monumental federal immigration laws passed, and in one case repealed, during the early- and mid-twentieth century. In the ’20s, Americans were uneasy at the rapid pace of demographic change as a result of the great wave of immigration, disproportionately from Eastern and Southern Europe, during the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. Even though these newcomers were overwhelmingly European Christians of various kinds, many Americans felt that they were culturally distant enough from the older Anglo-Protestant stock that having the foreign-born represent nearly 15% of the population was problematic. They feared, for instance, Catholicism changing moral and political habits, or ethnic and linguistic barriers creating ghetto-like parallel societies. The Federal Government answered those concerns. In his 1923 annual message, President Calvin Coolidge pledged that ‘America must be kept American’.

To that end, Congress passed, and Coolidge signed, the Immigration Act of 1924, also known as the Johnson-Reed Act. The Act drastically curtailed all legal immigration by banning Asian immigration and reducing immigration quotas from most other countries to 2% of the number from that country present in the United States according to the 1890 census. The law capped overall annual immigration at just 165,000, down 80% from before 1914. Johnson-Reed arguably allowed a coherent, modern sense of American identity to metastasise, especially as the national experiences of the Great Depression and the Second World War brought people together and rigorous assimilation standards were adhered to. By 1970, the foreign-born share of the American population plummeted to an all-time low of 4%.

In the mid-’60s, amidst the fervour of egalitarianism associated with the great advances of the Civil Rights Movement, everything changed. Congress passed, and President Lyndon B. Johnson signed, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, more commonly known as the Hart-Cellar Act. Before Hart-Cellar, American demographics were quite stable. About 85% of the population was of European Christian — and predominantly Protestant — descent, with smaller minorities of African-Americans (a legacy of slavery and, of course, essentially an ‘ethnic American’ group in their own right), Hispanic-Americans (present in meaningful numbers, though very small by today’s standards, since American victory in the Mexican-American War and the westward expansion), and Native Americans (always present, but relatively small in number and only granted American citizenship in 1924). Other American minorities existed, of course, but they were very small indeed. The stable demographics did not mean there were no problems. The end of Jim Crow in the South is just the best-known example of the country trying to finally make good on its founding pledge to form a ‘more perfect Union’. But the stable demographics did lend themselves to a coherent sense of American identity, warts and all.

Hart-Cellar changed that without there ever being any kind of national referendum on the matter. One doubts whether the bill would have passed were citizens, or even legislators, aware of what its consequences on the American body politic would be. In fact, Democratic elected officials in support of Hart-Cellar lied to — or at least misled in their shortsightedness — the public about the consequences of the law. At the bill’s signing ceremony in New York City, President Johnson reassured the audience that ‘…this bill that we will sign today is not a revolutionary bill. It does not affect the lives of millions. It will not reshape the structure of our daily lives, or really add importantly to either our wealth or our power.’ Rather, Johnson supposed, it simply removed unfair restrictions to prospective immigrants on the basis of their place of birth, an immutable characteristic. Senator Ted Kennedy (D-MA) was even more explicit, arguing ‘…our cities will not be flooded with a million immigrants annually… the ethnic mix of this country will not be upset.’ Whether or not Johnson and Kennedy were being cynical or genuinely trying to fulfil the promise of America, the consequences of their crusade and the shift in philosophy and self-understanding it represents cannot be overstated.

We see its political effects now. At the time of writing, the Indian-American Zohran Mamdani, born in Uganda to Hindu and Muslim parents, is the leading candidate to be the next mayor of New York City. He is running on a platform that can charitably be described as in favour of extremely big government and welfarism at the expense of traditional American understandings of free market capitalism and self-reliance; interested in ethnoreligious blood-feuds that have their roots thousands of miles from American shores; and soft on crime. All the while, he seems eager to import, and stymie efforts to deport, as many people as possible who share those sensibilities. Omar Fateh, born in Washington, DC to Somali immigrants, is doing much the same in Minneapolis, Minnesota, while taking extra pains to stress the domestic threats supposedly posed by white Americans.

It is important to differentiate in this debate the aggregate and the individual. It is entirely possible, even probable, that there are given individuals of virtually any cultural group on Earth capable of fully assimilating into historical American culture to a degree that would make them behaviourally and philosophically indistinguishable from the pre-’60s revolution archetypal ‘American’. The idea is that the more culturally distant from historical American culture a prospective immigrant’s nation of origin is, the less likely he is to be such an individual. For example, one could argue that the few dozen Afrikaner refugees recently accepted by the Trump administration are, on average, very likely more able to successfully assimilate into Anglo-Protestant American culture than prospective immigrants from most other places, on average. After all, the Afrikaners are largely Protestant Christians of Northern European descent with long histories of, for instance, firearm ownership, frontiersmen culture, and private property rights. Some of them even chose to settle in the United States as farmers in places like Alabama and Montana.

I do not write any of this to be intentionally divisive or inflammatory, but to honestly ask: in what sense are men like Mamdani and Fateh the compatriots of those who cherish their ancestors who fought for independence and a new nation while cherishing the heritage that made it a recognizable new nation at all? How are they the fellow countrymen of John Marshall or Henry Clay? What do they have in common? Is it simply that they all happened to be present on the American landmass and granted government documentation stating that they are all equally American? These are serious questions that deserve serious reflection and answers.

If Paper Americans are Americans, then nobody is an American by any reasonable standard that I can discern. Token fealty to abstract notions such as ‘one-person-one-vote’ or ‘respect all points of view and religions’ no longer seem to be adhered to — let alone sufficient — to grant the sense of communal neighbourly affection throughout the nation that Alexis de Tocqueville observed during his journey through the early republic.

It is certainly worth acknowledging that there are countless bona fide descendants of American settlers who do not live up to the ideal of the pre-’60s archetypal American. Nonetheless, if a coherent, concrete substitute for traditional notions of American identity cannot be identified, what is left of America will continue her decline into a banana republic parody of her former self in which social trust and quality of life continuously deteriorate for all of us, newcomers and old stock alike.

This article was written by Levi Boone, a Pimlico Journal contributor from the United States. Have a pitch? Send it to pimlicojournal@substack.com.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing. If you are already subscribed, why not upgrade to a paid subscription?

This is a fascinating article and I want to read that Albion’s Seed book now. That said, I think theres a missing factor that even if there was the intention to found an Anglo Saxon Protestant nation, the decision to import large numbers of Africans to work the plantations means that America was *in fact* a mixed nation of WASPs and African Americans from the beginning, and I’m not sure that can be ignored in favour of the intention of the original English settlers — after all, the original intention for America was to be under the control of the British Crown!

American identity is at least part European, part Native, part Negro, part Mexican.