The Strait of Gibraltar: Britain between Africa and Europe, part 1

The European Side: Gibraltar and Campo de Gibraltar

Gibraltar

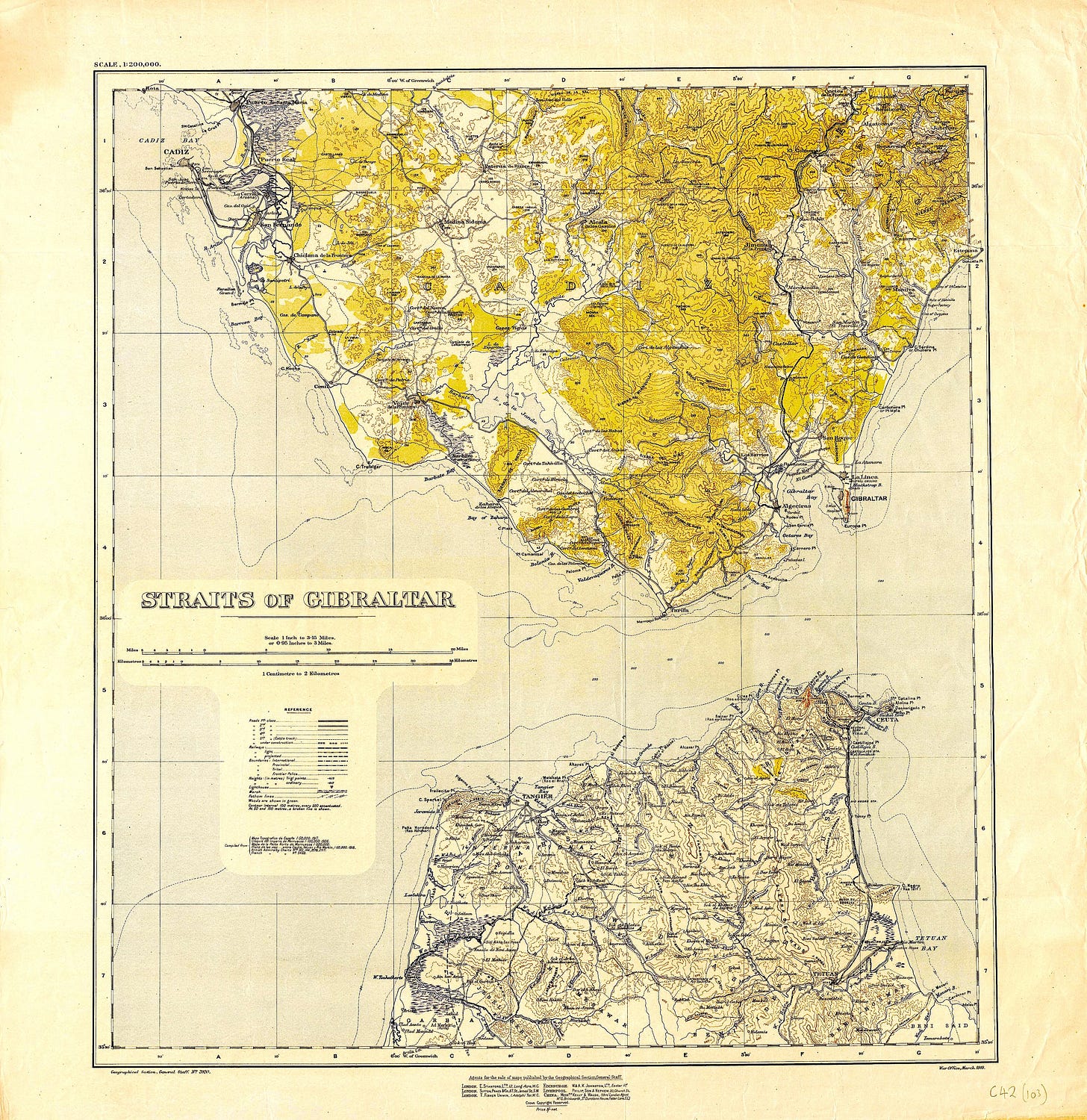

Held to be the key to the Peninsula since Antiquity, as well as an impenetrable stronghold for whoever had the might to keep it, the Rock of Gibraltar is situated on the most strategically important point of the Iberian Peninsula, with the advantage of calm waters and milder winds on the eastern side of the Strait. Due to its coveted position, on the European continent only Istanbul has faced more sieges. In the early days of the imperial administration, Britain sought to give Gibraltar — which was ceded by the Spanish in the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht — all the capabilities of a fortified military base in the homeland to deter any attempt by the Spaniards to retake it. This undertaking came with a hefty final price: the diversion of important naval resources during the fourteenth and final Siege of Gibraltar (1779-83), originally intended to deal with unruly colonials in North America.

But sea blockades are now a distant memory. The Georgian howitzers and the 100-ton Victorian cannon are on display only as tourist attractions. Peace reigns in this corner of Europe, with new endeavours preoccupying the inhabitants of The Rock in recent decades.

After the Francoist regime closed the borders with the British enclave in 1969 — an odd thing to do to a NATO ally, at a time of growing world trade and with a US military base one-hundred miles away — the local Gibraltarians turned to the refuelling of cargo vessels and Soviet whaleboats. Around the same time, with its new special tax system, it managed to attract multinational businesses to set up headquarters there. These eventually grew to be the cornerstones of its current economy. Against all odds, and in spite of its relative isolation, Gibraltar has remained profitable, now boasting of being able to cover the expenses of higher education in the UK for the Gibraltarian youth.

The closest comparison to Gibraltar would be the former colony of Singapore (despite the former having a population of under forty thousand, as compared to the latter’s six million). Both stand out for their strategic location, massive bunkering operations, and explicitly commercial orientation. Despite actually being less dense than Singapore, Gibraltar somehow feels livelier and more concentrated: the entirety of Gibraltar can be walked, from north to south, at a regular Londoner pace, in around eighty minutes. At any point of the day, there’s always a few construction sites on the works or renovations of old buildings. Adding to it, the docks have constant activity, even on a weekend. The locals show, like the Singaporeans, more proximity and easygoingness, but are closer to the pre-Internet way of doing things (similar to the neighbouring salaos Andalusians), greeting each other, and even an obvious outsider like myself, with a ‘mornin’ on their noon stroll, far from the tourist areas. Such pleasant and down-to-earth attitudes are reflected in Gibraltar’s fertility rates, the highest of any British city and among the highest of any Catholic-majority city in Europe.

That Gibraltar is a ‘British city’ is no exaggeration, neither for the natives nor for the visitors. Many of the elements one could find in a relatively nice town in Northern England are also present here: a World War I memorial, a Leeds United supporters’ club, a cancer charity trust, a good antique shop, some high-rise apartment buildings, a nice Main Street, a decently-sized Marks and Spencer, and ‘Ashley is a slag’ graffiti. Although most Gibraltarians have spoken a variety of Andalusian Spanish since the Reconquista, the population has, as of late, increased their day-to-day usage of English. This is mostly due to a curious part of modern Gibraltarian culture: many of the young adults going to British universities end up meeting their future spouses there, who are disproportionately native Brits and don’t speak any Spanish, thus nurturing English-speaking households.

Though Gibraltar benefits greatly from clear skies and mild temperatures year round, the city feels welcoming beyond its inherent touristic appeal. There is a certain warmness which remains unchanged after every visit. It is, to put it simply, a nice place.

Campo de Gibraltar

The area surrounding Gibraltar is made up of various municipalities constituting Campo de Gibraltar, a comarca (county) in the province of Cádiz. Tarifa, a small town in the southernmost point of the Iberian Peninsula, has intense Levant winds year round, making it an undesirable location for daily ferry routes to Africa, but a renowned spot for surfers worldwide. A sprawl of luxury real estate, summer homes for many celebrities, is situated on the sheltered hills near its coastline, with far less paparazzi than the bigger Marbella and Málaga. A little bit further east, as a middle point between Tarifa and Cape Trafalgar, lies the playa de los alemanes (the ‘German Beach’), a local favourite among northern European retirees, with a rather peculiar backstory: it was here where some high-ranking Nazi officers spent their twilight years, far from the spotlight.

Both Cádiz and Campo de Gibraltar share the dubious honour of being among the regions with the highest unemployment rates of the entire European Union. Though Cádiz itself is on par with the rest of the Andalusian provinces, Campo de Gibraltar is slightly out of place considering the variety of businesses and industries located in the area: an oil refinery north of the Bay (the biggest in the entire Peninsula, supplying the Gibraltarian businesses refuelling cargo ships); the shipyards to the south; the giant wind-farm north of Tarifa (so big it can be seen from Africa); and the deepwater port of Algeciras, located opposite Gibraltar.

There’s two main reasons for the gap between the statistics and the reality, accounting for tens of thousands of supposedly ‘unemployed’ Spaniards. The first, and most famous, is drug-trafficking. Single-trip trade routes expand from the Guadalquivir (a river that leads to Seville) to the Port of Valencia, involving several networks of locals, Portuguese, Galicians, Colombians, and Arabs of various nationalities. With their mini-submarines, 1000-hp motorboats, and camouflaged fishing vessels, smugglers overpower and outrun the police boats, even in broad daylight. It’s not hard to see why the dark trade remains so alluring for the youth: it offers incredible views of the Strait, cat-and-mouse play, light prison sentences, and a day’s labour easily pays as much as the monthly minimum wage. Seeing the sunrise on the blue horizon, I find myself wondering if I still have time to switch careers.

The degree to which drug-trafficking escapes the control of the Spanish law enforcement agencies is hard to assess. Policemen are at the risk of injury and, even as recently as a year ago, death if they get in the way of the drug boats. Apart from the military training camp near Tarifa and the various bases and warships spread on both side of the Strait, a Spanish Navy patrol boat carries out watch duties on the entire area, recently detecting the presence of a Russian submarine and escorting it out of the Strait. But even so, the Chief Inspector of the Economic and Tax Crimes Unit (which dealt with money laundering, among other matters), was arrested in November 2024 after being caught with twenty-million euros in cash, almost certainly bribes from drug traffickers. This is likely only the tip of the iceberg, given the sheer amount of money involved: last year also saw the largest seizure of cocaine in Spanish history, thirteen tonnes, hidden in bananas entering Algeciras. The street value of this cocaine, once cut, was estimated at between €2.3 and €3 billion.

As homicide rates remain among the lowest in the West and drug-related deaths are below the EU average, it has been accepted by society at large that massive amounts of illegal substances will inevitably trickle into Europe through Spain, whether circumstantial or deliberately unchecked. The end-consumer — whether the upper-middle class yuppie or the down-and-out junkie — is more than happy to turn a blind eye to this situation whilst supply remains so high and prices so ridiculously low. If the Strait of Malacca is a maritime bottleneck, with Singapore doing everything in its power to avoid becoming a natural hotspot of the global drug trade, the Strait of Gibraltar is in a similar situation, albeit with Gibraltar itself being somewhat impermeable.

The second main reason for the unemployment statistics is underreporting. The inhabitants of Campo de Gibraltar often choose to work... in Gibraltar. The data differs, from 2,000 registered foreign workers in Gibraltar, to the 10,000 workers who cross the passport control on the ‘fence’ daily, with some variations depending on the season.

Despite Gibraltar being the main employer of their neighbours to the north, the simple act of crossing the border between two countries with freedom of movement agreements has been subject to constant friction over the years, much to the despair of the locals. Spain, as it is well known, wants the European ‘Pillars of Hercules’ back, one of its main symbols on its coat of arms and flag. It will, often unprompted, push for its reincorporation into the mainland by various means.

The irredentist position on Gibraltar in Madrid couldn’t be further from the position held by those locally. This is best illustrated by the good relationship between Gibraltar’s Chief Minister, Fabián Picardo, and the Mayor of La Línea, Juan Franco. Last October, when a sudden spike in border checks by the Spanish police was countered by the Gibraltarian police, Franco called for a demonstration, hoping that this would help lead to a deescalation of the situation. However, this protest was not targeted against the foreign government south of the Bay; rather, it was targeted against at the government in Madrid. Sure enough, the Spanish side unilaterally suspended the measures at the border, which was soon reciprocated on the Gibraltarian side.

The Spanish state is, in a sense, the only outlier in an otherwise smooth multi-party relationship. It is no wonder that Juan Franco, one of the most popular elected officials in Spain of the last decade, winning three-quarters of the vote in the most recent elections, is now looking for ways to make La Línea an autonomous city, akin to Ceuta and Melilla on the other side of the Strait.

Such positive relations between neighbours despite a tumultuous backdrop can only be reminiscent of the cheerful attitude at the end of the Great Siege of Gibraltar, the longest siege in the history of the British Armed Forces:

3rd February 1783

This morning we received (by a flag of truce) intelligence of the most joyful and enlivening nature, which for some time, belief appeared doubtful; but after a few hours of suspense, we had the happiness of being in possession of the particulars, brought by the Spanish flag boat. The Duc de Crillon has sent his compliments to General Elliott, acquainting him that the different courts had agreed upon a cessation of hostilities, and that the preliminary articles of peace would shortly be signed. The garrison, enraptured with the sound, spread the harmonious tidings, and in the evening all firing ceased on our side, agreeable to an order sent by his Excellency the Governor to the different posts. The enemy's cannonade became silent in the afternoon. During the night we fired a few light balls in the isthmus, to discover the situation of the enemy.

I scarce know how to begin upon a subject so truly interesting and captivating. Our situation is changed from noise and confusion, to calm serenity. The atmosphere that was continually disturbed with flames and smoke, is now illumined with variegated brightness; the stars that have been so long eclipsed, now shine with their wonted splendour; and the bespangled rays of Aurora, with resplendent lustre again adorn each hill and height, that for upwards of eighteen months, has only been distinguishable by the flashing of pieces of ordinance. Our sudden change from war to peace, the tranquility that presides over the battered Rock, and Andalusian shore, so powerfully affects all ranks in the garrison, that to give you the delineation, would be a talk for an able writer. The power of oratory, the mot persuasive eloquence, would fall infinitely short in describing our happiness and amazement. Will you believe me in asserting, that every post last night appeared peculiarly solitary, by the silence which all around prevailed, and the hours of slumber seemed uneasy, for want of that martial noise, to which we have been so long accustomed.

I shall now proceed to give you some account concerning the effect upon our late determined antagonists, who seem highly to participate on the blessings of peace.

They appeared in crowds this morning upon the isthmus works, evincing every demonstration of the most heart-felt and lively joy, sending forth unfeigned and rapturous congratulations. The long wished-for sound of peace, re-echoes from shore to shore, from hill to hill, from rock to rock, and every tongue is filled with the blissful melody. The Spanish officers at noon came underneath our lines, bowing to the guards, assuring them that an amicable peace had actually taken place.

Our Governor has not made any reducement in the number of the guards, not knowing how far the stratagems of war might operate, but waits until the royal declaration arrives from England, when every testimonial will be made as a thanksgiving to our great Creator, for the restoration of the invaluable and inestimable blessings of peace.

—Samuel Ancell, A Journal of the Blockade and Siege of Gibraltar (1793)

If there were any doubts about the present good relations between the inhabitants of Gibraltar and La Línea, a statue of a cross-border worker has been erected one-hundred meters from the passport control office, on the Spanish side.

This article was written by an anonymous Pimlico Journal contributor, based in Spain. Have a pitch? Send it to pimlicojournal@substack.com.

Part 2, discussing the African side of the Strait of Gibraltar, will be published next week.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing. If you are already subscribed, why not upgrade to a paid subscription?

I lived in Gibraltar for two years in the early '90s. To classify the locals as 'entitled' would be an understatement. Gibraltar is a town, which thinks it's a country, and behaves like a village.