Few British governments have had much of a handle over pensions in recent decades; most politicians will see a role at the Department for Work and Pensions as a temporary (and in many ways, difficult and unpleasant) assignment before they move on to bigger and better things. Nevertheless, the British government seems to have gotten into its head the idea that pensions are currently a significantly underutilised source of investable funds that, with the right encouragement, could be used to boost a flagging economy. This is usually accompanied by complaints that pension funds are failing to sufficiently invest in UK equities — which have significantly underperformed their American counterparts, though some may argue this is something of a ‘chicken and egg’ problem — and private markets. Most recently, we saw calls for pension schemes to be required to report on their level of investment ‘in Britain’, although it is important to note that this will only apply to Defined Contribution (DC) schemes regulated by the FCA, not the Defined Benefit (DB) schemes which, given their age, make up a significant proportion of total pension scheme assets in Britain at present.

As someone who advises on the investment strategies of British pension schemes, it is always bewildering to see just how little policymakers seem to know about the structure of British pensions, and the hard economic (and regulatory) logic that has underpinned their investment decisions, however undesirable they may appear to an outsider. As such, the editor-in-chief has asked me to explain to Pimlico Journal readers the core issues that British pension schemes are currently facing.

The regulation of Defined Benefit schemes in Britain

The focus in this article will mainly be on Defined Benefit (DB) schemes, given that these are where most pension scheme assets are currently held (as these schemes are older, meaning that there has been more time for money to be paid in). But first, a brief note on Defined Contribution (DC) pension schemes, which are what most Pimlico Journal readers (who are younger) will be used to dealing with. In DC schemes, your employer will normally provide a ‘contribution’ based on a percentage of your salary. This ‘contribution’ will be placed into a pension pot which you will then have responsibility for investing profitably. This, helpfully from the employer’s perspective, removes the need for the employer to worry about making sure that these assets grow: that responsibility is now all on the employee. Most people on a DC scheme will be placed on a bland ‘Default’ strategy, which will see someone in their twenties invested in bonds and other ‘safe’ assets with poor returns. Unsurprisingly, at my firm, most individuals have self-selected their pension to be nearly entirely made up of global equities while they are young, which is the cheap and sensible option for building a strong retirement pot if you are looking from the perspective of returns. Perhaps something that some readers may wish to note!

DB schemes are, almost without exception, far more desirable than DC schemes. Unlike DC schemes, DB schemes require the employer to guarantee the employee a certain income at retirement based on some predetermined commitments, often an employee’s final salary. It will be no surprise to most readers that the vast majority of ‘open’ DB schemes are for the public sector, including Local Government Pension Schemes (LGPS), of which the Greater Manchester Pension Fund is one of the largest, with over £18bn of assets. DB schemes take all of the responsibility away from individual employees; instead, they place the burden squarely on the employer, who must invest wisely so that they can supply all of the benefits that they have promised. Importantly, these benefits are often RPI or CPI linked. In the private sector, any shortfall must be paid by the sponsoring employer; in the public sector, the shortfall will — naturally — be met by taxpayers.

One of the key facts about DB schemes is that they tend to have their liabilities measured on a gilt-based discount rate. This is used as a proxy for the amount of future pension benefits that the scheme will need to pay out, and therefore provides an estimate of how much is required to meet all of the members’ needs. The use of gilts is also due to the fact that they represent a low-risk investment, hence reflecting the low-risk nature of pension liabilities. Pension schemes are also required to project member benefits a number of years in the future, so gilt yields — which are also a proxy for long-term interest rates — help align the valuation of the liabilities to their long-term values.

As such, whenever we consider the investment strategy of a DB scheme, we don’t necessarily care that much about the absolute level of assets. Instead, the main concern is the level of assets against the liabilities. Every three years, a DB scheme has a valuation in which an actuary will tend to use gilt-based assumptions to put a liability figure on the total member benefits that are expected to be paid out. These liability figures can vary enormously from valuation to valuation.

DB schemes fell out of favour as costs for employers to maintain them increased. This was partly the result of falling mortality, which has left employers paying out benefits for longer than they expected, as they are obligated to pay the pensions of members for the duration of their life. But perhaps less obviously, this was also partly a result of increasing regulation of pension schemes, especially following the Pensions Act 1995, a response to Robert Maxwell’s fraud against the Mirror Group’s pension scheme.

The Act included provisions such as:

The aforementioned triennial actuarial valuations of the plan. These calculate the present value of the liabilities, based on a number of assumptions such as a discount rate — generally gilts based — and mortality — the longer your members are expected to live, the more you will end up paying out.

A requirement to state a ‘Minimum Funding Requirement’. This saw employers forced into improving their funding position to ensure that they could pay out benefits in the long-term. This could include paying more into the plan, rather than relying upon investment returns on existing assets.

Before the Act, even some smaller companies operated DB schemes in order to attract employees; after the Act, the costs of such regulation meant that these schemes became excessively burdensome for these smaller companies and they were mostly discontinued.

Furthermore, there was also significant accounting reform to the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) in 2005. Following these reforms, companies were required to recognise any pension deficit or surplus on their balance sheets. After 2008, this became a serious issue: the funding position of most DB pension schemes plunged for obvious reasons, as the low interest rate environment and tepid market recovery that followed forced employers to pay more into their schemes rather than rely on their investment strategies to make sufficient returns.

The ‘ESG’ grift has only further increased burdens on pension schemes. Endless pointless documents abound, wasting staggering amounts of money and time. For example, DB schemes are now required to produce ‘Implementation Statements’: these require pension schemes to report on how their investments have promoted ‘ESG’, in terms of the votes of the underlying holdings. In practice, this is essentially pension schemes — who typically invest in cheap pooled passive equity funds from the likes of BlackRock and Legal & General — reporting on how they have ‘voted against’ a company’s management in some random area of ‘ESG’. Often it seems obvious that the likes of BlackRock will vote against management in cases where they know that the vote will pass just to give them something to talk about on their annual stewardship report. Another common example I’ve seen is an asset manager voting against the likes of Bezos and Zuckerberg to be on the boards of Amazon and Meta respectively for the sake of ‘strong governance’.

A more recent type of ‘ESG’ document is the ‘Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures’ (TCFD) report. This is an even more fruitless exercise which sees schemes pay ridiculous amounts to their investment advisers to measure various carbon metrics for the scheme and make pledges on how they will improve it in the future. In practice, it is common for schemes to de-risk (i.e., replace equities with gilts) in order to massage the numbers to fit some pointless target, giving themselves a pat on the back in the process. If you ever wanted to look at any of these documents, it is required that they are all published online. Some of the most amusing ones are those of the large oil and gas companies: Shell’s TCFD report states that their Scope 1 and 2 emissions for the pension scheme’s assets fell 38% in just one year, thus meeting their 2025 target already. The real cause of this ‘improvement’ was merely a reduced allocation to equities.

How leveraged gilts ‘de-risk’ a DB scheme

Given the burden on the employer, what tends to happen is that as the funding level of DB schemes improves — i.e., as the level of the plan’s assets rises against the liabilities promised — they tend to de-risk — i.e., they remove growth assets, such as equities and property, and replace them with gilts and bonds. Given that the assets are there to track to liabilities, which are calculated on a gilt-based discount rate, gilts are a natural investment for these maturing DB schemes.

Most remaining DB schemes are not open to new members; as a result, most of the remaining risk to these schemes tends to be from interest rates or inflation. As such, most schemes will invest in gilts of different maturities in an effort to match their interest rate and inflation exposure. The now-infamous leveraged gilts are a very common method of achieving this insulation against interest rate and inflation risk, often under the banner of ‘Liability Driven Investment’ (LDI). A scheme essentially borrows cash to purchase additional gilt exposure through gilt repos and the use of derivatives, such as interest rate and inflation swaps. Adding leverage to gilts sounds crazy, but in most situations (more on this later) it is fairly safe, with dedicated collateral (usually held in liquid money market funds) held alongside the LDI funds.

When there is a rise in the yield of gilts, the value of the LDI assets fall, as would be expected; but when using leverage, it greatly amplifies the impact. For example: say there was a 10% rise in gilt yields. If the LDI has leverage of 3.5x — as was previously standard, before a ‘certain event’ — then the leverage would see the fall in the value of the LDI assets instead be equivalent to 35%, not just 10%. The leverage now increases, and you would therefore be required to use your collateral to buy more gilts in order to maintain your level of interest rate and inflation protection at a lower level of leverage which is deemed more acceptable. This is key for most DB schemes, as most target 100% of their liabilities in order to practically immunise themselves from interest rate and inflation risks, and often over 50% of total assets are in LDI. Most schemes used to have enough collateral to see around a 1.5% increase in interest rates before they would be forced to disinvest their other assets, but this all changed after the Gilt Market Crisis of 2022.

In September 2022, Truss and Kwarteng’s budget spooked the markets, most likely as a result of their unfunded tax cuts. This caused real yields to rise; with this, the value of the gilts held by DB schemes plummeted. The collateral pools evaporated overnight, and DB schemes were forced to sell other assets. Where a number of investors at once were redeeming, this led to higher spreads (and transaction costs), and schemes generally removed any liquid assets they had. After the crisis, rather than the focus being on the high levels of leverage that most DB schemes were operating under, the narrative has been to blame the British government for destroying people’s pensions — despite the fact that with yields at recent highs, DB scheme pensions are now at around the same funding level as they were in the crisis.

Moreover, before the crisis, the regulator was pushing for investment into leveraged gilts as a method of managing risks, not realising that billions are now invested in gilts with a very small number of LDI managers (there are only really four or five managers which pension schemes use). Indeed, each DB scheme has to pay a levy to the Pension Protection Fund (PPF), which is a body that pays compensation to DB scheme members whose sponsor becomes insolvent, as happened with the likes of Carillion and British Steel. This levy is based on the risk profile of the DB scheme in question, and leveraged gilts are thus one way of reducing this payment.

With the focus on continual de-risking, and with a lot of DB schemes now having strong funding levels — mainly due to liabilities tanking, as yields rose from 1% to over 4% — the ultimate end has been these schemes transferring their liabilities to an insurer rather than running down the scheme, as the cost of this is deemed too high. This is known as a ‘buy-out transaction’, where the insurer is then responsible for paying the benefits to members. Of course, this comes at a premium for the scheme, with insurers requiring an amount which broadly represents the present value of the liabilities on a prudent basis (roughly gilts + 0.0% p/a). Given this, when a scheme is transferred to an insurer, it is done in a portfolio of gilts based on the scheme’s liability profile. The insurer will then simply hold these until maturity and pay out the benefits to members.

Pension funds do invest ‘in Britain’ — just via government debt, not equities

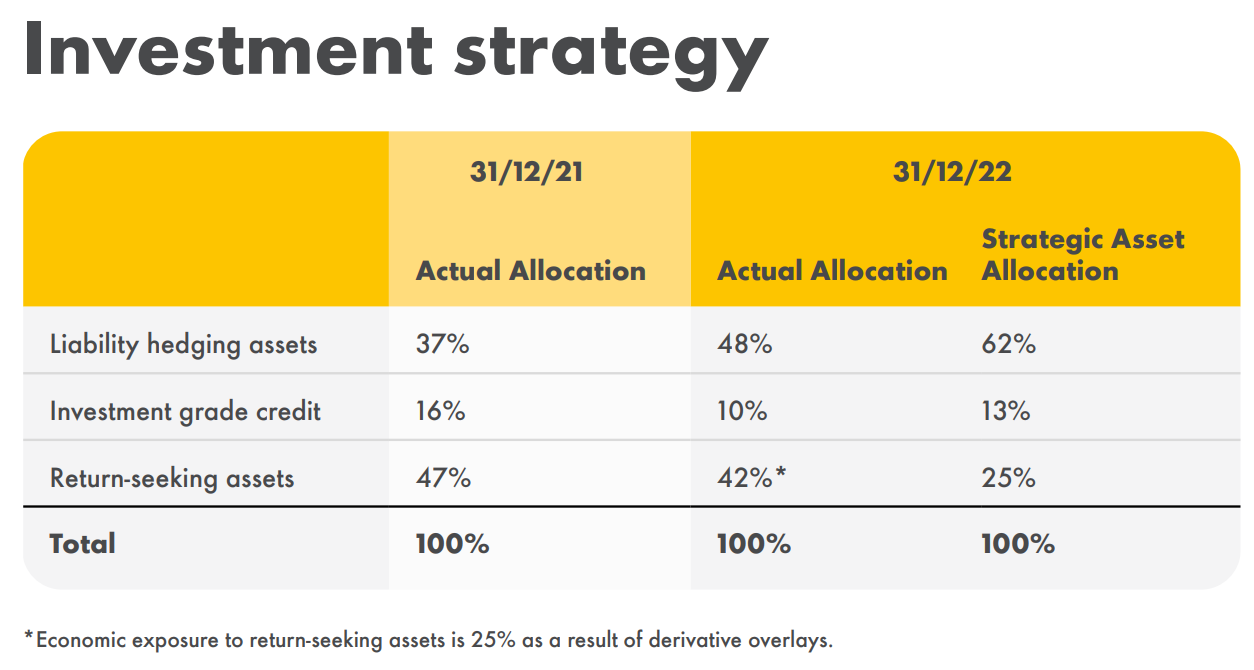

The result of all of this has been that DB schemes are, contra Jeremy Hunt, investing more than ever ‘in Britain’. It is just that much of this investment ‘in Britain’ is investment via government debt. It is not that they are ignoring Britain; it is just that they are not investing in British equities or private market assets. Going back to the example of Shell, they currently have a 48% allocation to ‘liability hedging assets’ — that is to say, with near-certainty, to leveraged gilts. As such, Shell’s pension scheme almost certainly already has over half of its assets invested ‘in Britain’:

As to why pension schemes more generally aren’t investing in British growth-based assets (as opposed to government debt): these assets, relative to alternatives, generally have unattractive returns. Moreover, even if we acknowledge the ‘chicken and the egg’ problem, they are generally poorly diversified, heavily weighted towards a small number of companies, disproportionately in oil, mining, and pharmaceuticals — and given the obsession with de-risking, this is not good for a pension scheme. Looking at a recent breakdown of the MSCI UK Top 10 Constituents, the top 10 — five of which (Shell, AstraZeneca, BP, GSK, Rio Tinto) are in the three aforementioned industries — now make up around half (48.95%) of the full index:

Why would I want to have a significant exposure to UK equities if that is all I am getting?

In any case, on a simple market capitalisation argument, Britain is as large in terms of global capitalisation as it was a few decades ago, with global markets (and therefore global returns) dominated by the United States, with China slowly increasing its presence.

Some of the push from the government is around private market assets — private equity, private debt, infrastructure, etc. — but although the returns on these tend to more attractive than those on UK equities, they come with significant fees. With a simple pooled global passive equity fund having minimal fees — around 0.05% for an institutional investor — why bother with private markets, which tend to charge over 1% in fees alone, before even accounting for any performance-related fees? On this fees point, this is yet another reason for pension schemes moving away from UK equities: it is now fairly cheap to invest in a currency-hedged version of a passive global equities fund.

Overall, there is little truth to Jeremy Hunt’s claim that ‘British pension funds appear to contribute less to the UK economy than international counterparts do’, given the staggering gilt exposure that British DB schemes now have. If anything, a geographical breakdown would show a bias towards Britain. I do accept that Jeremy Hunt’s argument is somewhat more valid for DC pension schemes — where there is actually more of an investment case for British assets outside of government debt — but private markets have not been that accessible for DC schemes as of yet.

If the British government wants more investment ‘in Britain’ outside of investment in government debt, then they need to remove some of the barriers to investing. On both the DB and the DC sides, this should include assessing the utility of a lot of the ‘ESG’ regulation — which hits equities but not gilts — with the ‘Implementation Statements’ in particular considered a joke to most people in the industry. On the DB side, there needs to be more incentives to increase the appetite of trustees for risk if their ultimate aim is more investment in UK-listed companies, as the current system encourages the exact opposite; however, this is near-impossible whilst companies have to worry about any deficits (however temporary) from these schemes on their balance sheets. On the DC side, the focus needs to be on unlocking investment opportunities: most of these funds are currently stuck in bland ‘Default’ strategies, which give an inappropriately low weight to equities and private market assets. This, however, is slowly changing, as more money accumulates in the DC pension schemes, which now cover the vast majority of the working population.

Image rights: Ted Eytan, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0

This article was written by an anonymous contributor who advises on pension investment, based in London. Have a pitch? Send it to pimlicojournal@substack.com.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing. If you are already subscribed, why not upgrade to a paid subscription?