Reform and the future of welfare

Controlling the public finances, part 1

Whilst the fundamental reason for Reform’s surging popularity, and indeed political destabilisation across Europe, is demographic replacement, the proximal cause of Keir Starmer’s collapse in popularity — and the issue which will eventually bring down his government — is his failure to make positive change on the economy. Trapped between looming fiscal crisis, stagnant growth, and back benches which refuse to countenance any cuts in spending, his Chancellor will be forced to raise taxes from already-record levels in this month’s much anticipated budget, kicking the can down the road whilst rendering prospects for future growth all the more dire.

Nigel Farage has profited from Starmer’s inaction, but that he is terrified of the challenges he will inherit is clear to see in every interview he gives. He is correct to be concerned. The issues we have today are different to, and in many ways more diffcult than, any this country has faced since the war. After decades of depoliticisation which have seen economic management outsourced to the Treasury, the Bank of England, and a range of ‘independent’ regulatory organisations, our ability to think politically about economic questions is greatly atrophied.

It is for this reason that, when politicians and commentators attempt to propose reforms, they are rarely able to do so without falling into platitudes which boil down to re-running a highly-simplified Thatcherism (or social democracy for those on the Left). Regardless of the merits of these ideas in their time, this is cargo-cult economics. Our specific challenges require new and particular responses.

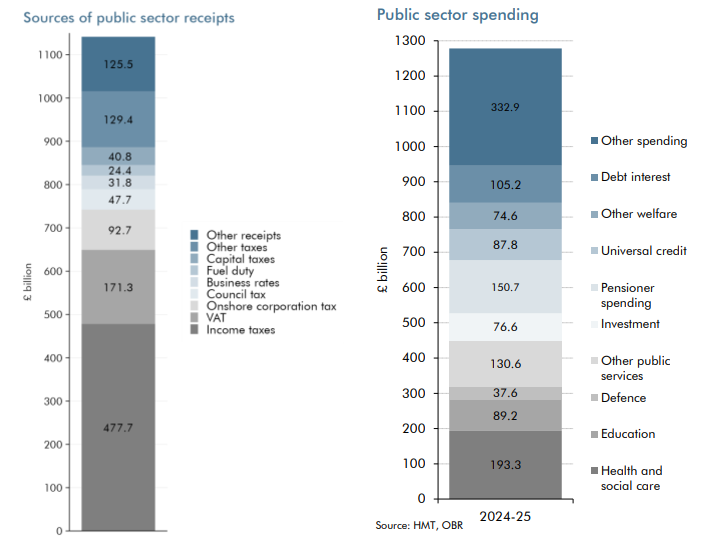

The first challenge that any new government will face is dealing with public finances. Assuming the government continues to take 40% of national income in taxes, and it is safe to assume that it will barring radical change, private sector investment and personal savings will continue to be squeezed, and strong growth will be impossible. Equally importantly, with public sector debt to GDP now above 100%, international financial markets are no longer willing to provide the British state with the benefit of the doubt that they once were, as demonstrated by persistently weak gilt prices. This makes public finances less resilient to economic shocks and restricts the government’s ability to spend.

Taxes must come down, and so must debt. Expenditure must therefore be reined in. This is not the simple project many wish it to be. The lazy libertarianism that many on the right are so tempted by refuses to confront fiscal and political realities that keep spending high. The failure of Coalition Government to seriously reduce spending and the colossal under-achievement of DOGE in the US demonstrate that there is rather little to be gained from simply looking to run existing systems more efficiently. Attempts to drive efficiency by reducing budgets have led to an NHS with fewer doctors and nurses, less capital, and worse health outcomes than comparable countries. Whilst this may have constrained cost increases, few could argue it represents increased ‘value for money’.

All this shows that bringing down spending cannot simply mean reducing budgets across the functions of government. It must be achieved by re-evaluating what services the government provides, and how it delivers those services. Where should this evaluation start?

It hardly needs to be said that the rise in debt interest payments is the most obvious and immediate cause of the current fiscal difficulties, and that reducing those payments by eliminating deficits will be a necessary first step in overcoming them. Recent climb-downs by Reform on the tax promises made at the last general election indicate a recognition of this.

It’s also clear that savings can be made by eliminating Net Zero plans, currently forecast to cost approximately £10bn in investment and £20bn in lost revenues per year (although the true costs may be higher, especially in the form of suppressing economic growth), and from eliminating funding for other leftist social and political causes. None of this alone, however, will make the impact needed to seriously improve the fiscal situation whilst enabling taxes to fall.

Whilst defence spending — as highlighted repeatedly by Dominic Cummings and others — is a source of great wastage, any savings made here will be reinvested, and will not have a significant net fiscal impact (especially given recent pressure by the US for European countries to increase defence spending). Similarly, whilst the education system requires a great deal of reform, it is more likely to be a target for investment rather than savings — other than a potential restriction on student loans, which Reform might reasonably target after the election.

The most attractive target for savings, then, is that which has been the primary driver of spending increases over the past three decades: the welfare state. Healthcare, social care, pensions, and working-age benefits. Of course, these aspects of the state have been a libertarian bête noire for almost a century. Yet arguments for their abolition have fallen on deaf ears.

It is important to note that this is not simply due to the particular political culture of post-war Britain (as references to the NHS as a ‘national religion’ tend to imply). In any society which has been through the transition into economic modernity, and which therefore has seen structures of social organisation outside the state (churches, guilds, extended families, friendly societies, etc.) dissolved as individuals become mobile, dynamic economic actors and are uprooted from ‘traditional’ communal bonds, the state will be forced to extend itself into areas of life traditionally managed by those old structures. Such circumstances obtain now more than ever.

For this reason, regardless of one’s ideological preferences, the question is not how to abolish the welfare state outright, but how to reform each aspect of it such that costs can be controlled and to avoid the ever-more apparent perverse incentives produced by existing systems. We must consider the purpose of a welfare state in our time and ensure that the model of delivery aligns with it.

Today, most income-based welfare is managed through the Universal Credit (UC) system. UC is available to anyone on zero or low income, and pays £400.14 per month (£316.98 for under-25s). In addition, UC reimburses your rent payments (whether to a private landlord or for social housing) up to a limit set at the 30th percentile of comparable properties in your local area.

Various additional grants are available under UC based on particular circumstances: for example, those with children. For each pound earned, universal credit payments decrease by 55p until they reach zero. UC was first implemented under the Cameron government, and replaced most other income related benefits (most of which are now closed to new claims, although legacy claimants often continue to receive them).

The second largest component of DWP’s working-age welfare spending is disability benefits, now mostly managed through the Personal Independence Payments (PIP) system. This combines a cost-of-living payment of £73.90 per week (£110.40 for the more severely disabled) and a mobility payment of £29.20 per week (£77.05 for the more severely disabled). This mobility payment can be used to lease a brand new car at heavily discounted rates through the Motability Scheme. PIP is not affected by income or savings. There are dozens of other smaller benefits available, but they make up a small percentage of the welfare budget.

It is well understood that these benefits are open to abuse. Reform has recently drawn attention to a number of egregious issues with PIP eligibility. UC was originally implemented in an attempt to get those on out-of-work benefits back into employment, and claimants are required to agree to personally tailored commitments to certain job-seeking activities. The fundamental problem with this approach will be known to anyone who has experience with the system or who has known someone using it: these restrictions rely on enforcement by benefits officers who have little incentive and even less desire to force claimants back into work. If anything, attempting to change the behaviours of the long-term unemployed, or to force claimants to accept jobs perceived as below them, makes their job harder and more stressful.

All said, in its first years UC was semi-successful in reducing numbers of long-term unemployed on Jobseekers Allowance and placing them into some work rather than none. In doing so, it encouraged recipients to take on part-time and casualised work, in part contributing to the wider restructuring of the British labour market towards lower-value-added, lower productivity forms of employment in hospitality and the ‘gig economy’. As of this year, so long as claimants in work meet the ‘Administrative Earnings Threshold’ of £952 per month, they are placed in the ‘light touch’ regime of intervention from their work coach, not being expected to look for better or more work. In combination with the generous personal tax allowance, though UC lowered the real expenditure on unemployment assistance, it produced limited dividends for the Exchequer, and in the long-term began to operate as an indirect subsidy for parasitic sectors of the economy, with poor employment practices and limited potential for long-term investment in desperately needed productivity gains.

There is some scope to limit disability benefits by tightening PIP eligibility, especially by eliminating mental health conditions as viable criteria. Even this, however, is fraught with difficulty given that some of Reform’s current and target constituencies are among those with the highest rates of PIP claimants in the country. Even then, a large portion of claims are likely to remain untouched due to the same principal-agent problems with benefits officers. For those not already also on UC, removing PIP eligibility may simply encourage them to submit new claims — not exactly saving any money. Merely reforming eligibility criteria is therefore unlikely to lead to a radical reduction in spending; at best, it could temporarily curtail the near-exponential growth in claims since COVID. What is required, then, is not ‘reform’, but a deeper rethinking of the purpose and structure of welfare.

Looking back on the development of the welfare state can help us identify alternative possibilities. National Insurance, now nothing but an income tax by another name, was originally established in 1911 as part of then Liberal Chancellor David Lloyd-George’s wider reforming agenda, which modernised the antiquated patchwork of local welfare provision via the Poor Law. Instead of seeking solely to resolve the external issues of ‘pauperism’ and vagrancy, the act was a recognition by the state that many working people faced hardships in their lives to which they had no sufficient recourse, like sickness or cyclical unemployment, especially if they found themselves without the assistance of a union or membership in a friendly society. Expanded in 1920, it was initially what it describes itself as: a system of health and unemployment insurance, originally a guarantee for those in highly cyclical or dangerous forms of employment to not be made destitute by poor luck, and from which only those who contributed to the scheme could draw. Payments on ‘the dole’ were limited to fifteen weeks, during which time claimants were expected to find new employment and were subject to the means test, which was felt – and intentionally so – to be intrusive and shameful. Pensions were notably exempt from the National Insurance scheme, and were limited by the means test and to the poorest of ‘good character’.

William Beveridge turned the basic idea of a social insurance system limited to workers into one that was universal, compulsory and, by emphasising a flat rate of contribution, free of shame for all citizens. Individual National Insurance contributions would be invested in government securities, which would accrue interest and could be used for one’s unemployment coverage in the face of hardship or for pensions. Instead, the 1945 Atlee government retained the universal component of the Beveridge Report but shed the contributory requirements in creating the modern welfare state, leaving NI the vestige it is. Conservatives Iain Macleod and Enoch Powell sought to roll back Labour’s socialism whilst retaining paternalistic commitments to the idea of a safety net for the poorest, and published the pamphlets One Nation: a Tory Approach to Social Problems and The Social Services: Needs and Means in which they argued for the introduction of charges in the NHS and means tests for all state benefits. Conservative governments would widen applications of the means test, but rather than shrinking the state or rolling back socialism, would only further sever the link between a working, productive individual’s contribution to ‘the system’ and the benefits they receive. Far from the intended consequences of testing, the types and total costs of benefits received by a growing proportion of the population have ballooned, at the expense of those who receive little to nothing. Max Tempers/the Nick 30 ans poster complains that he pays for the 90% of prescriptions that are dispensed on the NHS for free, as well as the one he might use in a year. By restricting support to the ‘most vulnerable’ alone, the ‘welfare state’ ceased to be a system of an individual’s insurance against potential misfortune and has become ever more a tool of blanket economic redistribution and social policy.

Eighty years later, we can see how the redistributive model has failed. Ultimately, whilst the state may impose various requirements and penalties on welfare claimants, no government will be willing to force citizens to take on a job they do not wish to take. If a person cannot be forced to take on work, and if their access to benefits is not conditioned upon having worked and contributed to an insurance scheme, it should not be surprising that so many choose to remain un-or-under-employed — especially when finding work may in many cases involve moving to a new location, transitioning into a different industry, or taking on an unglamourous or unpleasant position.

The impact of this can be clearly seen across the country. Large swathes of England are filled with economically dead towns, where those unlucky or unmotivated enough not to have secured a public sector job can scrape out a meagre existence on welfare, perhaps sharing a bartending position in the local pub between three people to top up their income without harming their UC claim too much.

Most readers will not be of a disposition to understand this choice. If you have graduated from university and moved to London or another large city in pursuit of an exciting career, the prospect of relocating for a job seems undaunting — but when such a relocation means moving from one place to another to find a job at the local supermarket, leaving friends and family in the process, it isn’t hard to understand why many would choose poverty so long as they can still get by.

The fact that this choice is understandable does not mean it is one we should continue to subsidise. By allowing people to choose welfare dependency, we are allowing our country and its people to rot, rather than face the hard realities that economic change creates. One of the distinguishing characteristics of England throughout history has been the geographical mobility of the English, to the extent that at the level which distinguishes Bavarians from Badenese no genetic distinction can be made between a Northumbrian and a Devonian. The loss of this dynamism is a great tragedy.

Ending this failure requires a return to the foundational principle of the British welfare state — that those who work should be shielded from destitution as a result of factors beyond their control, but that benefits must depend on contributions. Replacing unemployment benefits with a new contributory system is necessary to achieve this.

How would such a system work in Britain today? There are two possibilities worth considering, depending on the extent to which one expects risk to be socialised. The first — which will be attractive to more libertarian minded readers — is a Singapore-style national savings account, to which workers will be required to contribute a certain percentage of their income until contributions reach a certain monthly cap. This savings account could either be managed by a central investment fund akin to Beveridge’s scheme, or (more ambitiously) individuals could be permitted to allocate their funds to a range of privately administered approved funds.

Such an account will be entirely individual — you will only be able to take out that which you personally have put in — and withdrawals would be limited to certain purposes. For the purposes of this conversation, that includes funding basic expenses in the event of unemployment, but as will be explored in subsequent pieces, this account could also be used as a basis for reform of other social services.

Whilst attractive as a basis for broader reforms, the main challenge such an approach faces is that eliminating socialisation of risk entirely will be politically challenging in a democratic country. The alternative, then, is a system of national insurance which functions as any insurance product, and therefore does not tie pay-outs proportionally to contributions. Under such a system, all employees would be required to pay a certain percentage of their income into an insurance system which would entitle them to a defined benefit upon becoming unemployed.

The advantages of this system are primarily political — every worker would receive the same benefit, and could rely on some kind of relief without having had to contribute a particular amount during their period of employment. This benefit, and the contribution rate, would have to be set such that the system as a whole operates sustainably without the need for subsidisation through other taxation — but the original offer of national insurance (up to 15 weeks of basic expenses) seems a reasonable starting point. If such a system sounds too redistributionary (since higher earners will pay more into national insurance), the benefit could be redefined with a universal living expenses payment and a variable housing expenses payment.

Either of these systems would be a productive basis on which to reform welfare, end long-term voluntary unemployment, and control ballooning public finances. Both provide potential models along which other aspects of the welfare state could be reformed. It is worth noting that such reforms will only be socially and politically viable if paired with reforms to the labour market, reducing competition as a result of immigration and making it easier for people to find work which matches their skillset — but such reforms are beyond the scope of this article.

Whilst reducing the burden of the state will not on its own be enough to fix Britain’s broken economy and return growth to the private sector, it is certainly a necessary first step. Only by adopting a new model of welfare can we hope to control costs, and ultimately reduce taxes as a result.

This article was written by George Spencer, our Managing Editor, and Francis Gaultier, a Pimlico Journal contributor. Have a pitch? Send it to submissions@pimlicojournal.co.uk.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing. If you are already subscribed, why not upgrade to a paid subscription?

References

OBR, A Brief Guide to the UK Public Finances

King’s Fund, Comparing the NHS to the health care systems of other countries

House of Commons Library, Local Government Finances

OBR, The working-age, health-related welfare system in the UK

I like how cuts to defense is waved away with “But the Americans won’t be happy!” As if that means anything to British voters.

Because OF COURSE, defense cuts are a huge part of fixing the budget.

Scrap both aircraft carriers, along with Trident and nuclear subs. Britain doesn’t need them, and though British politicians will loathe to admit it, they’re a very expensive leftover from when Britain was a world power. It hasn’t been for decades, and it can’t afford pretending.

The key stumbling block is that UC is now deeply embedded in all groups in our society, including in those who claim disabilities, such as mental health. The old 'get on your bike and get a job' mantra will be political suicide, especially for Reform if they took loudly vocalise it before 2029. It is now a deeply felt entitlement for many 'working' class British people. I see it on many pages where they gather or those they know.

I'm aware that it's not a Pimlico-favoured policy, but I believe more attention should be given to considerations around Sovereign Money, as outlined by people like Adair Turner and Richard Werner, as a complement to traditional bank credit. A transition period with a ten year plan.

And a remigration policy, which both opens up more lower level employment, whilst marginally raising wages.