Property Taxation and Meritocracy? A history of Land Value Taxation in Britain

A 'Blue Jumper' Shibboleth Revisted

Taxation on land and property in this country has never been uncontroversial — the Englishman’s home is, after all, his castle. Stamp Duty Land Tax (SDLT) is by far the most unpopular tax in the country. Nor is this unusual in the English-speaking world: one of Ron DeSantis’ final initiatives as Governor of Florida, in an expression of boomer populism, was his attempt to repeal property taxes entirely; meanwhile, an increasingly standard feature of American discourse is vague gesticulation against the malign influence of ‘BlackRock’ buying up single-family homes in these states. Yet Texas, which has no state-level income tax (one of only nine of the fifty states) but relatively high property taxes (seventh highest of the fifty states), though it may be distasteful as the new home of ‘The American Millionaire’, has become the most ‘liveable’ Sun Belt growth state and seen rapid population growth from internal migration.

Britain is an outlier in the developed world for having no standardised system of property tax. This was not always the case: in the 1909 People’s Budget, the Liberal government introduced Land Value (amongst other new) taxes, inspired by Henry George, Radical land economy, and a desire to wage class war against their traditional enemies. These taxes were introduced by Chancellor David Lloyd George — the same man who would later repeal the taxes as the Prime Minister heading a Conservative-dominated coalition in 1922. Of course, we do still have Council Tax (levied on 1991 property values to fund local government) and Stamp Duty Land Tax (paid to the Exchequer and collected as a one-off lump sum transaction tax by the buyer of a new property). On current rates, the average receipt from a buyer is £4,547, and for a property worth £500,000 (a standard 3-bed in the South East), the SDLT bill would be an additional £15,000 upfront. The first-time buyer exemption threshold was lowered to £500,000 last April, making it increasingly unimportant for those who are looking to settle down in a family home in the South East of England. The additional, steep immediate expense of moving house predictably gums up the property market and has damaging secondary effects on productivity by making it harder for workers to move to areas of higher demand. It also leads to volatile revenues for the Treasury, since the receipts are based upon the level of market activity in any given year (which is highly variable), making budget planning more difficult. Probably the only advantage SDLT has is that it is easy to administer, not requiring regular property valuations and being difficult to evade or avoid.

It is already a Blue Jumper truism to ‘just abolish it’. Most of the free market think-tanks (especially the Adam Smith Institute, and to a lesser extent the Institute for Economic Affairs) have advocated reforming SDLT — pointing at former ASI Executive Director Sam Bowman’s ‘Housing Theory of Everything’ — and, bearing in mind the need for revenue, have occasionally suggested Land Value or Property Taxes as a replacement. The technocratic Institute for Fiscal Studies has taken a similar line. On this issue at least, tax specialists and advocates of a smaller state are broadly aligned.

Today, though, the mainstream reformist position in this country’s politics is now to bring SDLT rates to zero without a replacement. The two parties that are most likely to be in government after the next election have already promised something to this effect and have both made pledges in this direction: Reform has pledged to lower rates to 0% on property values below £750,000, and graduated in new thresholds peaking at only 4% for values over £1.5 million; the Conservatives, meanwhile, have pledged to abolish Stamp Duty entirely. (Current rates are held at 2% from the lowest threshold of £125,000, reaching up to 12% on values above £1.5m.) The core issue remains that the full abolition advocated by the Tories would lead to a static revenue loss of approximately £10.38bn, whilst Reform’s 2024 Manifesto commitment — thus far surviving the more recent turn away from populism towards fiscal conservatism since November — would lead to around a loss of £7.3bn, after dynamic effects on the property market. Given the current fiscal climate and continued bond market skittishness, radical tax-slashing — though clearly desirable as a long-term goal — is not a decision to be taken lightly. Simply arguing that tax cuts are somehow ‘self-funding’ is not going to cut it, especially in property (due to the inelasticity of the market).

Despite speculation before the Autumn Budget that Rachel Reeves would try to overhaul SDLT and introduce a property tax of some kind, this proved to be a damp squib. Even aside from the problem of lost revenue, repealing SDLT is administratively challenging. Introducing a new property tax at this stage, if it were to function similarly to other annual property taxes around the world, would mean ‘double’ taxation on those who have already paid a full SDLT bill. Needless to say, this would be deeply unpopular without some kind of transition system. Sadly, Reeves instead opted for a populist, backbench-pleasing ‘Mansion Tax’ — i.e., the High Value Council Tax Surcharge — which places an annual 1% tax on properties valued over £2 million, starting at an extra £2,500 and increasing to £7,500 per annum on properties over £5 million. Additionally, taxes on property income will be increased, applying from 2027. As such, a complete overhaul of SDLT remains a growth-enhancing opportunity for a less sclerotic future government.

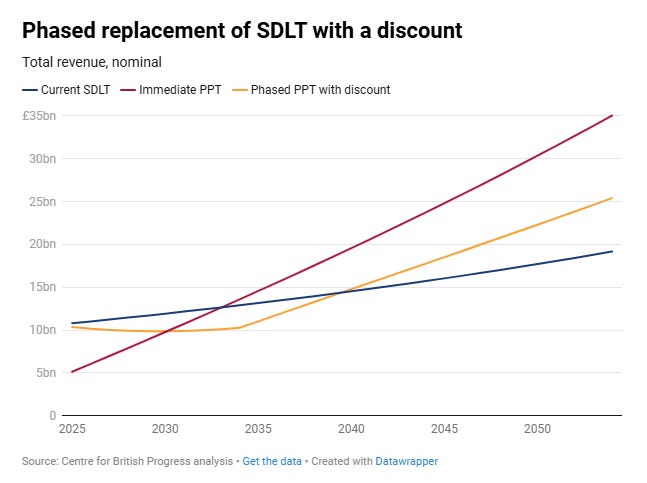

A transition system to a full property tax that utilises an opt-in at the purchase of new properties only on the part of the buyer, such as this one proposed in a paper (which you should all read) by the non-partisan Centre for British Progress, would create a small short-term revenue loss, but in the medium term would become revenue positive. Simultaneously, it would unlock the property market by addressing SDLT’s distortions, with real dividends found in the resultant productivity and growth gains. In the CBP’s study, they found that the replacement of SDLT with an annual broad-based property tax alone would deliver a permanent 3.38% increase to GDP, an approximate increase in the size of the British economy of £91 billion.

Economists across the political spectrum have favoured property taxes as the best way to raise revenue for the government whilst being minimally distortive (as well as being ‘progressive’, if they are of the left). For various reasons, if left unchecked, real estate tends to be the object of excessive speculation, leading to sharp booms and busts. Beyond being a source of revenue, then, the Texan example (among others) is insightful: taxes can be just as useful in discouraging overspeculation in a single asset class and, ideally, can function as a stimulus to improving the efficient allocation of resources, if not more elusive ideas of fairness. Stamp Duty is, of course, just one more way in which the diminishing number of people that did ‘the right thing’ — and frankly, at this point, given the way the ‘graduate jobpocalypse’ will be going in the next few years, the ones who were simply lucky — are sheared for all they have. Of course, we cannot deal with tax policy on the terms of what is amenable to one’s own demographic cohort over another. But it is exactly because of this that the younger generations, who have been given a raw deal through the ongoing student debt crisis, COVID, and the present graduate economy deserve better.

This is an old story by now, but let us repeat it once more. A modestly successful 26-year-old white-collar employee with a master’s degree, living in London on a salary of £50,000, will face an effective marginal tax rate of 57%. Add to this exorbitant rents and social dysfunction, it is obvious why young professionals are increasingly desperate to leave the country. Getting the property market moving, encouraging development (particularly in and around the major cities) and lowering the overall tax burden on these people is the best thing we can do for them. The state (and especially right-wing political parties) has a long-term interest in ‘getting people started’ — that is, fostering an environment in which individuals can develop some stake in the system (such as through property ownership and family formation), and particularly so for the largest demographic reserves of intelligence (and future wealth creation) in the population, lest we lose them to other countries where they will get a better deal.

Taxation across all groups has to come down, yes, but it is for this demographic in particular which work — and this is almost necessarily a long-term project — must begin most urgently. Rethinking how we approach taxation is only the start. The core principle behind a Land Value Tax (LVT) — that productive labour should not be taxed, while dividends from rent-seeking behaviours can be socialised — is fundamentally why it is still a popular alternative for the aficionados of political economy, just as it was in 1909. This popularity is despite Land Value Tax’s well-known political and administrative failures, both at home and abroad. In one sentence, Land Value Tax is favoured for ethical as well as practical reasons. LVT, or an approximate property tax that captures the same principle, will be essential in substantially shifting the tax burden away from young professionals with relatively high personal incomes and onto older, more established, and asset-rich demographics. In light of both the dire fiscal straits the British state finds itself in, and the wider problem of a tax system that is unfit for purpose and increasingly unfair (most of all on the young and aspirant), it is worth considering the history and underlying principles of property and income taxation to guide us towards the right path forward.

Radical Liberalism, Henry George and the Underconsumptionists

In his essay in Works in Progress, Sam Watling pushed back against the great Blue Jumper shibboleth by appeal to a detailed history of the failed 1909 Liberal Land Value Tax. To respond in full, I have to offer an alternative account.

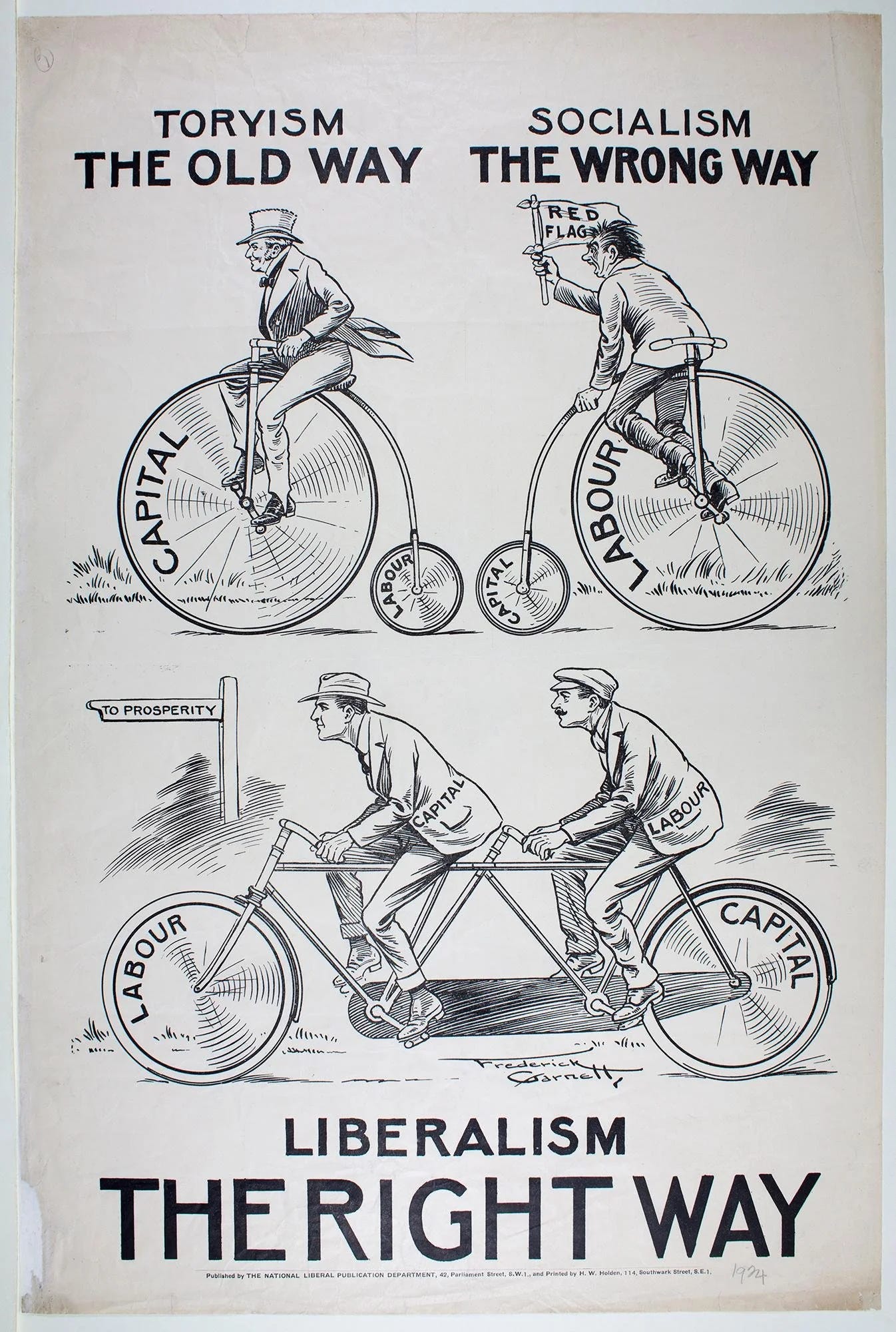

The Liberal party of Gladstone’s day was divided between Radicals and Whigs. The Whigs were effectively a parliamentary clique drawn from the great landowning families who happened to be more metropolitan and vaguely constitutionalist than the Conservative ‘country party’. Insofar as they had a coherent ‘political economy’, it was derived from a mastery of the idioms of progress they had acquired, making them able mediators of the interests of ‘the people’, the political nation and crown in their glory days. They have little obvious relevance to us today, but will be important in framing the politics of this story.

From the perspective of 2026, the Radicals are far more interesting. They had a more identifiably modern — and perhaps modernising — ethos which came out through their desire to politically elevate commerce and industry over the landed and agricultural interest. They came from largely middle-class urban, industrial, and nonconformist backgrounds. The core of their economics was a distrust of unearned privilege and a grievance with what they called the ‘land monopoly’. Though they were good capitalists, in their view land differed from other kinds of wealth because it represented a natural monopoly: industrial enterprises could be expanded by hard work and good business sense, but land was (and is) mostly fixed — since land is as necessary as oxygen, those fortunate enough to have inherited it were able to exploit the community and individuals forced to rent. The enemy of the working man was therefore not the capitalist, but the landlord.

Capitalist heroes Richard Cobden and John Bright saw the country as in the grip of a sinister feudal conspiracy, with an anachronistic aristocracy held over from a time in which society was organised for warfare, not industry. They were broadly anti-interventionist in foreign affairs and saw the growing list of Conservative imperial entanglements as an outgrowth of this anachronism. Even the British constitution was a ‘…thing of monopolies, Church-craft, sinecures, armorial hocus-pocus, primogeniture and pageantry!’ Even though he predated the Georgist turn of the Radicals, in his last speech in Rochdale in 1864, Cobden argued for a ‘…free trade league for land just as we had for corn.’

The influence of Ricardo’s theory of rent (1817) and Henry George’s Progress and Poverty (1879) was widely felt and provided the theoretical basis of a land economy in which rent-seeking could be condemned. George’s ideas themselves were actually deeply anti-urbanist; however, then and now, his disciples instead used his arguments to push for the intensification of land usage and to promote economic agglomeration and efficiency. George played a key role in moving the sympathies of a deeply anti-Catholic demographic (though even during the Home Rule debates, men like John Bright maintained the mantra ‘Home Rule Means Rome Rule’) to favour a policy of land reform in the interests of the Irish majority to break the weakest link of ‘Landlordism’ in the British Isles during the Irish Land War. Georgism took LVT logic to an extreme in the Single Tax Movement — in this view, all government expenditure could (and should) be funded by the socialisation of the land monopoly. The Single Tax would be a panacea: it would end unemployment, landlordism, and all manner of other social ills.

These ideas had always existed in an uncomfortable tension with the Whig elites in the party. In Gladstone’s second term the Radicals forced a confrontation with the Whigs over landlordism in Ireland which, along with Gladstone’s democratising impulses and the final straw of the failed Home Rule bills of 1886 and 1893, drove the vast majority of Whigs out of the party — and many into the breakaway Liberal Unionist party, which would later merge with Salisbury’s Conservatives. As Gladstone was finally leaving the arena, the Radicals were capable of forcing a full-throttled Radical agenda on the Liberal party in the 1891 Newcastle programme, which would shape the direction of party policy in the next decades. They committed the party to an expansion of property taxes along the principles of Land Value. (It should be noted that a form of this already existed in Schedule A, the part of income tax applied on both rental income and the estimated rental value of houses, ‘imputed rent’.) Local government also had to be funded, primarily by ‘the rates’ on domestic and non-domestic property, and came to be in a persistent state of fiscal crisis as varying demands on welfare benefits (as funds for the provision of the poor law had to be collected and provided locally) and expanding municipal duties (such as increasing demands for public infrastructure) led to highly uneven burdens on councils.

On top of the Georgist framework, Edwardian liberals were increasingly influenced by political economists like Hobhouse, Hobson, and Webb. They expanded the Ricardian theory of rent and made more sweeping prescriptions on the corrective measures. In the ‘New Liberalism’, the Radical attack on land came to apply to rental income, which was now viewed as entirely ‘unearned’. Anticipating Keynes, Hobson also argued that the domestic underconsumption of goods derived from the ‘oversaving’ of the wealthy that could not find an outlet at home. In his account, this would necessitate imperialism as an outlet for excess savings and surplus goods — it was a wasteful endeavour for anyone but the small class of financiers and aristocrats the Radicals identified with the Empire. In this interpretation, anticipating later Keynesian arguments on inequality and the marginal propensity to consume, the solution to underconsumption was social reform.

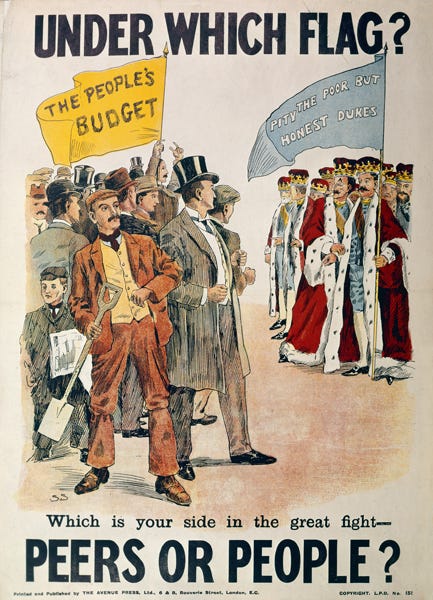

The People’s Budget and Failure of LVT

The old issue of Free Trade led the Liberals to win a stonking majority in 1906. In the aftermath, both parties began to embrace what Churchill had dubbed a ‘big slice of Bismarck’ in welfare policy, introducing contributory insurance systems for unemployment, pensions, health, and tighter workplace safety regulations. The real point of contest between the two parties became fiscal: whether social reform at home should be funded by increases in tax graduation, with the burden thus falling on those who held assets of land and capital, or if the costs of reform could be ‘externalised’ away from the wealthy, landed and domestic producers through Tariff Reform in a ‘social-imperial’ framework. Joseph Chamberlain (a heterodox Radical defector) and Viscount Alfred Milner had spearheaded the Unionist turn to a Bismarckian social and economic policy. This was a dangerous strategy, built on the growing feeling that the old Conservatives needed to embrace a new politics that could cut through class boundaries in a democratic age. In Trumpian fashion, they argued that protection, Imperial Preference, and Empire would reap dividends great enough to fund social reform whilst avoiding socialist graduation and supporting employment and industry. Chamberlain’s gambit failed. The 1906 electorate — by this point predominantly working and lower-middle class — remained unconvinced that tariffs were anything other than a trick of the privileged to retain the unearned increment of their wealth whilst they would foot the bill for reform in high food prices and protection for the landed.

The Liberals’ instrumental reasoning and presentation of the Land Tax followed a schema we are familiar with. On top of raising revenue from the unearned increment, the budget would create an incentive to develop underused property. Taxation would be a stimulus for economic activity; the Treasury coffers and the urban wealth of the nation would be filled together. It was a theoretically perfect tax, and it seemed initially to square all of the political circles they needed: it aimed to appeal to both labour and the middle-class; it avoided tariffs and on paper; and only those able to exploit land rents had reason to fear. Unfortunately for them, this last assumption was incorrect.

The pattern of decades of Liberal policy coming to a dead end with the unilateral right of veto of the upper house reached its zenith in the 1906 Parliament. Lloyd George and his base wanted a bust-up with the Lords — and they got it. The decision to unify around a platform of Land Tax was an effective declaration of class war — and, as much as it was influenced by Georgist and other ideas about land, was also motivated by a desire to finally subdue the house that had obstinately stymied liberal initiatives since the age of Russell and Palmerston.

The Unionists were equally keen to fight a constitutional (and extra-constitutional) battle against the Liberal attempt to capture the state. After facing their worst electoral defeat in history (until 2024), there were signs of recovery in a string of local elections. Perhaps the new approach would pay off? They campaigned on a wave of ratepayers’ revolts driven by smaller property holders, like shopkeepers, on fears of where land taxation could fall, and exploited a loss of enthusiasm for the Liberal platform on the other side. New Liberals complained that for Campbell-Bannerman’s government, the embrace of ‘social reform has not yet gone beyond the rhetorical stage’. This motivated Lloyd George to push even harder on the Bismarckian agenda. Following a trip to Germany, he stressed the urgency of social reform by tying its emerging military might and national strength to its progressive welfare programme. He was able to seize leadership of the Radical wing of his party from Churchill, preparing legislation for funding the new Dreadnought battleships, labour exchanges, old-age pensions, a national health insurance programme, and what would become the ‘People’s Budget’. All of this required new taxation, and the burden — so argued Lloyd George — had to fall on the landed.

Having lost the Whigs to the Unionists, the Liberals held less than one-tenth of the seats in the House of Lords. Convention dating back to the seventeenth century was that the Lords would not reject Treasury money bills, but the Unionists could not resist the bait. They chose to veto the budget, agreeing only to pass it if the Liberals won the next election. The first election of 1910 led the Liberals to lose 123 seats and their majority. 40 of those were to Labour; the Conservatives gained 116. The Liberals were forced into forming a coalition with the Irish Nationalists and Labour, which complicated matters further. To pass the People’s Budget, they now had to bring the old issue of Irish Home Rule out of cold storage. The constitutional crisis was still not over: after interventions from the King and threats to pack the Lords with 400 of their own new peers, the Liberals had to fight another election in December in the same year to pass the 1911 Parliament Act, which finally ended the unilateral Lords’ veto.

The ‘constitutional’ stage of the crisis was won, barely, by the Liberals. The next play of the Unionists was to mobilise the issue of Home Rule, offering explicit support to Ulster loyalist groups actively arming themselves to resist Irish majority Home Rule, and by extension the elected government. The country appeared to be on the brink of civil war.

The constitutional crisis had permanently neutered the House of Lords, and it was the People’s Budget, not protectionism, that inaugurated Britain’s Bismarckian welfare state, funded by steeper income tax graduation with higher death duties and the new land value taxes. The old system of property tax was easy to calculate: tax was based on the actual rent a property went for or the local authority’s assessment of its value based on similar properties nearby. The new taxes introduced all sorts of complexities.

Additional tax on revenues that landowners received from mining royalties was also introduced. This much was straightforward. But the transition to land value taxation, which took the form of a 2.5% baseline on undeveloped land and a 20% tax on unrealised increases to property value introduced the challenge of how the government would establish a baseline price of land against which increases could be measured. The tax also credited owners for improvements made to the land, but the process of calculating the numerous facets of improvement, such as value added by plumbing, infrastructure contribution or the building itself, had never been recorded. Of ten million properties in the country that needed valuation, few had been traded separately from the land they were on and records were poor. This meant that there was no way to easily determine the value of the land itself. Instead of hiring an army of tax assessors, the Liberal government introduced ‘Form 4’, which required owners to submit details on the income and numerous valuations of their properties, and landowners were required to self-assess.

The conservative constitutional defeat in the ‘People vs Peers’ crisis did not mean landowners would accept the new taxes (and indeed, the possible end of their way of life). Landowners immediately initiated a lawfare campaign in response to the land taxes and finally achieved victory in the Scrutton judgement of February 1914, effectively overturning government legislation in the courts, invalidating all valuations of agricultural land and blocking the 2.5% base on undeveloped land and the collection of the increment tax on farmland. In Watling’s essay, he argues that the taxes did not work as theoretically imagined — on the grounds that building fell in the years 1909-12, rather than forcing property speculators to develop the land they held, as it was supposed to. The failure of valuation meant that since the introduction of the taxes, they had only brought in £500,000, while implementation had cost £2 million.

While the Land Tax had been theoretically elegant, the idea had stalled in its application. But the government did not retreat from the basic objective, and Valuation would continue to be contested legally and otherwise. In 1914, Lloyd George attempted to reset the Land Tax agenda, attempting to allocate the funds raised by the taxes to local government (which had been squeezed on property rates in preceding years), and expanded LVT principles to the funding of councils. Lloyd George may have been a convert to the New Liberalism, but at heart he remained an old Celtic Radical. The target of his policy was always old, ‘unearned’ privilege. Even as the leading champion of social reform in the Liberal party at this time, Winston Churchill, baulked at the severity of the land duties as they were being conceived — Lloyd George noted of him, ‘he has a soft spot for dukes’. For him, the taxes were, in fact, an ethical and political good in and of themselves. The agenda was revolutionary, and the scope and limits of the revolution had to be worked out in real time.

The Feasibility and Results of Land Value Taxation

Based on the stalling of the Liberal Land Tax, Watling argues that a theoretically ‘pure’ tax is ‘chimerical’, and its failure set back the proper function of local government as well as the whole idea of property taxation in Britain. Though he is clearly intimately familiar with the relevant history, Watling’s account underplays the ferocity and polarisation of the political moment, and in doing so paints a misleading picture about the nature of the rollback. The portrayal of the effects of the Land Tax applied in practice is especially limited.

In the 1880s and 1890s, Britain was already going through a construction boom, particularly in dense urban housing for industrial workers. Land and credit were cheap while the City of London roared. New legislation like the ‘Housing of the Working Classes Act 1890’ enabled local authorities to clear slums for new terraces, and short-term housing demand was being met. The boom peaked in the years 1900-1904. After the global Panic of 1907, however, long-term building finance, especially in speculative housing, had dried up. Building had begun to fall in 1908, even before the introduction of LVT, and when discussions of valuation were just beginning. Vacancy rates were rising and rents had begun to soften, slowing new construction, and dock, rail and warehouse construction was beginning to dip cyclically with trade volumes. Credit tightening and saturation of the urban market alongside weaker population growth led to a construction slowdown. That building was declining is unsurprising, and a policy that could help throttle the property boom-and-bust should not be thrown out circumstantially. Signs of recovery were apparent in 1913 and 1914 before Britain found itself embroiled in a total war.

The political challenge can be considered by a straightforward comparison of the circumstances we are in today to both Unionists and Liberals of 1909-14, being willing to entertain a constitutional crisis over the issue of tax graduation is rather different to our own. Form 4 and valuation were indeed badly handled — but what ended the taxes was the war and coalition.

Lloyd George anticipated the battle over Valuation would continue and would become the central issue of the 1915 election. Watling notes that the government expected Valuation to take until 1917. This was under tense, pre-civil war circumstances. But instead of a civil war, Britain became embroiled in a catastrophic foreign war on the continent (which many initially thought would bring unity and relief from domestic strife). Any further development of the issue would have to wait. Lloyd George became Prime Minister via palace coup in 1916 and, again under radically different circumstances, was the head of the 1918 Coupon Coalition led by Conservatives with a smaller number of Liberals. The coalition was beset by myriad foreign entanglements during the peacemaking process and dire industrial relations. It was busy trying to reorganise the post-war economy, build 500,000 council houses, while also dramatically reducing spending across all departments. By this point, Lloyd George had sought the ‘fusion’ of his ‘Coupon’ Liberals with the Conservatives, which was a doomed effort. In the latter days of the coalition, Conservatives were able to force his hand on even the dearest of Liberal orthodoxies: free trade. The country’s politics had changed completely; there was no space to revive the Valuation question among all of this.

Based on this history, then, Watling’s suggestion that in the present day a Land Value Tax would be administratively impossible does not follow. Governments now have better resources at their disposal to reach a fair valuation. A start-up from Austin, Texas — ValueBase — has already created an algorithmic property assessment tool that can disaggregate the valuation of improvements, land, infrastructure, etc., thereby dramatically reducing the burden on private individuals or tax assessors. Similar schemes could be outsourced by government contract or developed in-house. Before there is any implementation of LVT, Valuation protocols should be established by committees to monitor the real estate market. Committees of this kind already existed in Germany before the help of algorithmic AI tools, and were carried out entirely manually. These committees track individual improvements and those from public ‘uplift’ or zonal development, and regularly publish standard land values. Once this has happened, the introduction of land taxation could be introduced gradually along the same lines as the ‘phase-in’ period of the Centre for British Progress’ proposal in reforming SDLT into a Proportional Property Tax:

Only apply from the next sale of a property. No current owner will be affected until they buy their next house.

Provide choice. Anyone buying a home in the next ten years can choose between either paying SDLT or committing to an annual PPT. Crucially, this means that no-one is worse off from this aspect.

Apply at 0.2% per annum for properties sold for between £125k and £250k, rising progressively up to 1.1% for properties sold for over £5m.

Completely replace SDLT: once a property has ‘transitioned’ away from SDLT (which can only happen at a sale), it is permanently subject to PPT.

Phased PPT introduction:

Buyers have the option of reducing their SDLT liability by a fixed percentage (10% in this case) in exchange for paying 10% of the new property tax in perpetuity. Each year, the portion of SDLT that buyers can opt to "switch" into PPT increases by 10 percentage points, until, 10 years after implementation, buyers have the option to switch fully out of SDLT.

Instead of using the rates held at the ad valorem property value, buyers would opt in at the proportionate (disaggregating the building of course, meaning this would be at a higher percentage of land value) discounted rate of the land tax and lowering the Stamp Duty bill. One core difference between the CBP proposal and this hypothetical implementation is land tax applies in full from the transfer of a property by inheritance or otherwise.

This proposal would assist in the fiscal transition out of SDLT and presents a feasible path to implementation of LVT while addressing much of the political fallout if we tried today. Once the transition period is complete, the next stage of the fight would be to raise rates on land whilst other earned income taxes (and spending) are cut substantially to reach a desirable equilibrium of taxation on unearned wealth.

A modern progressive taxation policy

Despite what it may seem thus far, I am not a partisan for a land value tax. As Watling points out, no other country has successfully implemented LVT, which does at least suggest something about the politics.

Australia, Taiwan, and Denmark are supposedly the three exceptions. Yet for the first two cases, Australia and Taiwan, the main uses of land — agriculture and occupier residences — are exempt from tax. These hardly count as examples of a genuine ‘Land Value Tax’. In the third case, Denmark, the theoretically pure case, the rates are so low and unobjectionable that it is basically irrelevant. What this is indicative of is the willingness (or lack thereof) of governments to challenge the political and economic power of the holders of land and mineral wealth, which will naturally vary from place to place.

Thankfully, Britain is now quite exceptional in this regard. We certainly no longer have a large caste of landowners dominating our politics. The most visible holders of larger tracts of land, farmers, do still possess outsized political influence in Britain (and indeed almost every democratic state they exist in). This is obvious in any political confrontation the agricultural sector has with the state, whether that be during Brexit negotiations over visas for strawberry pickers, or in the most recent case, forcing the (very weak and paralysed) Labour Government into its inheritance tax u-turn. Beyond votes alone, they have the physical capacity to clog up roads and worse; indeed, in Continental Europe, they are even willing to target their opponents with manure. I am typically someone who admires the lively, occasionally violent, democratic culture of the continent with its ceremonial rioting and ritual demonstration of people-power. But spraying one’s opponents with poo has no place in our democracy. These maniacs cannot be allowed to get their way.

Accepting they possess outsized political power, we should note these groups are unusually weak in Britain. Agriculture now contributes a miniscule 0.8% of British output, and employs about 1.3% of the total workforce. Services, on the other hand, account for 80% of the British economy and employs 85% of the labour pool. A capable leader could once again command the popular will to challenge the landed interest. The People vs. The Poo-sprayers.

The real political obstacle to an abstract Land Value Tax in Britain would not be farmers, but owner-occupiers — specifically those who live on high-value, low-utilisation plots, for example, the owner of a small house or bungalow in a major city. If implemented, LVT would be beneficial by encouraging owners of this kind to develop or sell the property. This would, of course, raise the challenge of the ‘cash poor, land rich’ pensioner or a low-income owner who inherited the property. I have mostly dealt with this already: the issue could be cooled somewhat by the fact that the land tax would not apply until the property’s sale or transfer to the new owner, as per the CBP schema established earlier. On the inheritance of property, the full land tax would have to be paid annually. This arrangement would be an unfortunate but politically necessary compromise. Those who have inherited stand to lose, but at least they won’t be able to wheel out a shivering pensioner on to the news orbit. A truly radical reassessment of questions of ‘merit’ and the socialisation of unearned wealth would also necessarily imply a redistribution of this kind of property.

Properly mobilised, an elected government with a revolutionary mandate to radically restructure the system towards flat (or at least flatter) income taxation to lower the burden on those making a start in life and on those with a wealth of underutilised assets, could force the issue with major goodies for urban professionals. But even if the tax is now both politically and administratively more feasible than it was in 1909, without the emergence of a great patriotic ‘Man of Push-and-Go’, in this aged democracy it is simply unlikely that a mandate of this kind could be earned by electoral means — sadly for both myself and Jack Anderton. The first hope is that a reforming government will take the interests of the ‘young, squeezed middle’ seriously enough to right old wrongs and make things fairer. A revival of LVT simply might not be a political battle a reformer would be willing to fight alongside other issues, but smaller tax policy changes alongside the meat-and-potatoes fixes in planning, energy and otherwise getting the economy moving, could hopefully capture elements of the same ends.

In this case, though theoretically weaker, a basic annuated ad valorem property tax scheme for residences and businesses would still improve the functioning of the market over SDLT and find an important source of revenue if other personal taxes are to be cut substantially. Implemented today, the Centre for British Progress’ recommendation of a Progressive Property Tax with a phase-in would be revenue-neutral by 2040 and raise more than SDLT every year after. Far from being a controversial new tax, the proposal would be an actively popular move that gives new buyers of property the option to defer heavy upfront costs. In and of itself, property tax could help shift tax away from income.

In this conversation of justifying the nature of graduation and socialising unearned wealth more sensitively, whilst also encouraging growth, another step could be to utilise the concept of Land Value Capture, that is, to have taxes on the windfalls of unearned land wealth increases, known as ‘uplift’, such as by the development of nearby property or infrastructure within zones designated for development, alongside the regular property tax. These two taxes can exist simpatico, provided the planning system is liberalised. The detailed work of taking planning out of the hands of local authorities to a national ‘regulation-only’ strategy will need to be explored in a future Pimlico Journal piece.

Developers often purchase and hold land in ‘land banks’, well in advance of the date they intend to build or have permission to do so. This is a problem as it leads to greater cyclicality in the land and property boom and bust. In theory, they should have little reason to sit on undeveloped land for any extended period of time. Due to our excessively restrictive planning regime, large developers are incentivised to speculate on land purchased cheaply and sit on it, sometimes selling it on without having built anything. A functioning planning system with Land Value Capture taxation would technically charge the developer with banked land, but the incidence of the tax would fall on the landowner by depressing the bids to purchase.

There is already an attempt to capture uplift in the British tax system, in Section 106 of planning obligations and the Community Infrastructure Levy — and stupidly, it falls on developers, raising the marginal costs of building rather than lowering unimproved land prices. The contributions are siphoned off to social housing projects or other aspects of ‘development’ that the authority deems important. Even worse, due to the negotiability of levies between local authorities and developers, levies can feature late-stage or surprise charges that function as a direct penalisation of development.

Clearer valuation protocols such as those sketched out earlier could monitor standard land values, charging higher rates of capital gains tax on undeveloped land nationally, outside of the local authority would eliminate the problems of negotiability and tax speculative windfalls. Land value capture policies in Hong Kong have raised massive revenues.

Conclusion

This article, much like LVT in political discourse, has sought to begin a conversation about the ideas behind tax differentiation more than it has sought to make concrete prescriptions. What I hope to have suggested is that, for all its challenges, the LVT idea and some of the forgotten aspects of liberal political economy generally pushed the wider conversation about the nature of tax differentiation in a fruitful direction. If we are to fix the fundamentally unfair British tax system, thinking more carefully about graduation than making statements about ‘just lower the taxes’ will be necessary. The old Radical argument that certain forms of wealth — for instance, wealth derived from the appreciating value of land — that are not earned by productive labour but by socialised effort should also be socialised is a useful and fair basis for graduation. In one sentence, we want to encourage labour and disincentivise indolence and inefficiencies. It is true that a single tax to this effect would be unlikely to raise enough total revenue for a modern state, but that does not mean that the general idea cannot underwrite our general approach.

The fundamental unfairness of steep income tax graduation is becoming apparent — even to Oli Dugmore! Or it is, at least in the (very limited) sense of that in his recent appearances on the New Statesman podcast: one of his main objections to the increasing rate of interest with higher earnings on student loan repayments, ie., exactly on its ‘progressivity’. Dismantling the university graduate tax scam (and shrinking the entire sector for posterity) is an obvious first step if Britain is interested in retaining its best. To this end, flattening the income tax curve and freezing the personal allowance will go a long way in ‘making work pay’. Outside of weak earnings growth, the most cited reason for the more soulless in our cohort wanting to work in Dubai is the absence of income tax. We aren’t likely to adopt a government of Sheikdom any time soon, so we won’t be able to just copy them. Graduation in other ways is therefore necessary to reach the goal of a flatter curve and overall lower tax burden. We should keep this in mind before making undirected anti-tax proposals and think about the appropriate share of imputed rental income, land value capture, inheritance, dividends, and Value Added Taxes that would also be needed to make up the difference. But these are big questions that must wait for another article.

It is on this matrix of taxation as stimulus for productive labour, and as a buffer on rent-seeking behaviours, empty speculation and indolence, that a modern, progressive policy should be derived. As the incidence of taxation has fallen too greatly on income (in various forms), and accepting the potential difficulties of LVT, taxation on the unearned increment can be introduced through a combination of smaller measures across the entire system. The alternative is one in which we continue to drift towards a bifurcation with a diminishing and highly stratified, productive taxable economy against a growing body of semi-employed, unproductive, effective day labourers who exist on state subsidy. But without a radical rethink of our tax structure, we are sure to continue to lose our best.

This article was written by Francis Gaultier, a Pimlico Journal contributor. He extends his thanks to Sam Watling for his work on LVT and David Lawrence and Pedro Serôdio of the Centre for British Progress. Have a pitch? Send it to submissions@pimlicojournal.co.uk.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing. If you are already subscribed, why not upgrade to a paid subscription?