Multiculturalism in Singapore, part 1

Singapore's three state-forming ethnic groups examined

This is Harry Yew’s second article on Singapore. You can read his first article, ‘A British expat’s life in Singapore’ (August 2024), here.

For decades, the European Right’s warnings about the contradictions of multiculturalism have steadily materialised — from the importation of petty inter-ethnic squabbles, to the complete inability of second- and third-generation migrants to ‘integrate’. Naturally, ‘solutions’ are proposed by the usual suspects on the Right with no memory longer than the last two news cycles.

The clearest example of this is the praising of Michaela-style, ‘neo-disciplinarian’ schools — an institution rightly described by Rhodes Napier as a hellish, panoptical experience for any British pupil of any good character. It epitomises the principle of excellence being smothered to appease middling, unconscious slavishness masquerading as order.

Singapore, often caricatured as a national-level Michaela School, is presumed to embody a form of Chinese petty authoritarianism: strict laws, immaculate streets, and inter-ethnic harmony achieved at the cost of individual spirit. The inference is that such a clean, efficient society must suppress deviance, particularly the kind produced by an unusually high IQ or genuine eccentricity. This perception is likely reinforced by the correct observation that although East Asians have a higher average IQ than Europeans, the distribution tends to cluster around the mean at the expense of the extreme tails. Thus, deviance — both of genius and eccentricity — is seen as inherently subversive. Singapore, in this view, is Michaelastan — a multicultural paradise sustained through state-enforced mediocrity.

The purpose of this piece is to correct the record. I previously wrote that life in Singapore as a foreigner felt remarkably free. People leave you alone. This may not sound romantic, but is foundational to any society with a claim to liberalism. This piece explains why that’s possible: why liberalism can co-exist with multiculturalism, and why it works in Singapore, but almost certainly wouldn’t work in Britain.

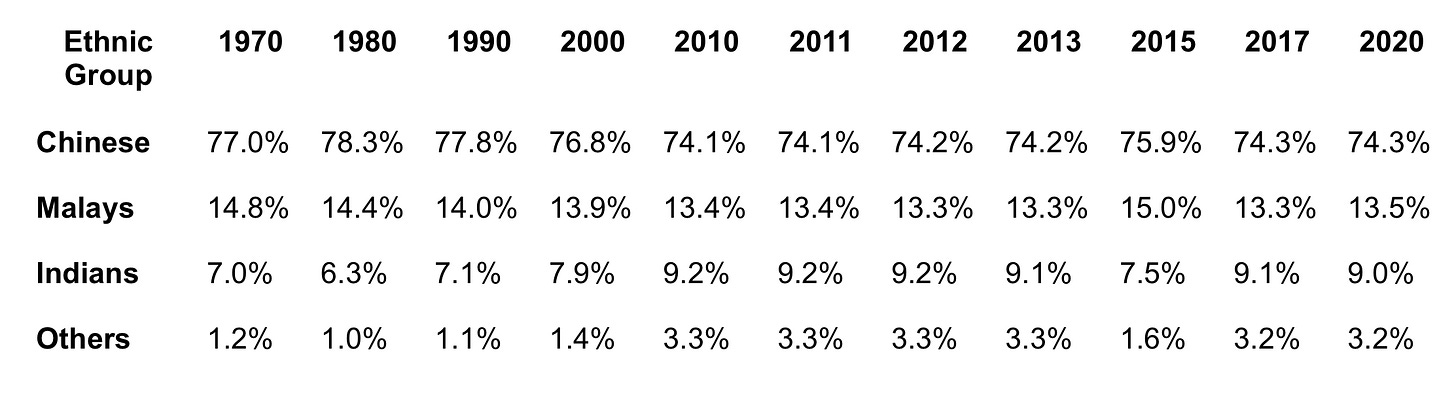

To understand multiculturalism in Singapore, we need to understand the cultures that comprise the nation, the Chinese (74% of the population), Malays (13% of the population) and Tamil Indians (9% of the population). We will examine how they came to be in Singapore, and how they fit into Singaporean society today. In Part 2, I will then venture into broader discussion about how Singapore as a nation-state is constituted.

The Malay Question

The Malays are often referred to as the indigenous people of Singapore, and rightly so. But even their demographic presence has been shaped by external movement. Following Raffles’ establishment of Singapore as a British port in 1819, significant numbers of Malays migrated from Johor, the Riau Islands, and Java. In census records, ‘Malay’ has long operated as a catch-all category encompassing not only native-born Malays but also Bugis, Javanese, and other Austronesian groups. They are understood as bumiputera (lit. ‘sons of the soil’, a term widely used in Malaysia itself and occasionally in Singapore also). Malay is constitutionally designated as the ‘national language’ (unlike English, Mandarin Chinese, and Tamil, which are merely ‘official languages’). And yet, their overall numbers have been kept relatively stable.

It’s important to emphasise that there is wide variation in terms of socioeconomic status and ‘eminence’ within the Malay population. Still, as a group, Malays are significantly more likely to commit crimes than the Chinese or Indians — a fact that inevitably invites comparison with Europe’s own ethnic dynamics, where groups such as Afghans, Moroccans, and Algerians are heavily overrepresented in a broad range of crime statistics. But this comparison is deeply flawed for two main reasons. First, the crime baseline in Singapore is extraordinarily low: Singapore is not Bradford. Second, the type of crime matters. Malay criminality centres around what might be called ‘market crime’: smuggling untaxed cigarettes (in Britain this is, frankly, a public service given our absurd tobacco duties, and I urge you to disoblige yourself of any sense of civic duty by condemning it), selling drugs, and importing vapes. This type of crime is not primarily violent (except sometimes against market competitors), and is very rarely predatory. It can perhaps be most closely compared with the crime committed by Albanians in Britain. Ultimately, the public perception of these crimes (even if you are strongly in favour of a crackdown) is often harsher than the moral reality. These are, at heart, entrepreneurial — not sadistic — offences.

Indeed, Singapore’s famously severe drug laws — harsher even than those for murder or rape — only make sense through this lens. The logic is pragmatic: the psychological ‘barrier to entry’ for drug dealing is far lower than for stranger rape, so deterrence must compensate (one might still prefer to Hang the Nonces, of course, but the logic stands). To equate the Malays with Britain’s worst-performing migrant groups is wildly off the mark, and the idea that Singapore suffers from the same form of parallel society or violent subculture found in parts of Europe is absurd. The Malays aren’t perfect, but they aren’t a real problem. As a proud Friend of the Malays, I will not have them compared to the worst-offending ethnic groups in Britain.

But there’s a more pertinent question than this, and that is the demographic trajectory of the country. Look at the above table. While the Chinese percentage of the population in Singapore has declined somewhat (and the Chinese population here is comparable to the white British in Britain), the key difference here is control. Singapore’s demographics are remarkably stable. One of the more noticeable trends I have noticed since returning to Britain after a long period of absence is that the perception of changing demographics causes pre-existing nuisance migrants to behave far worse than they would otherwise if they were living in a demographically pre-2015 Britain (leaving aside many of their default behaviours, which are already intolerable). Demographic momentum is a real phenomenon. The perception of whether it is our country or not has changed drastically in less than a decade.

Meanwhile, in Singapore, the People’s Action Party (PAP, Singapore’s governing party since independence) openly maintains ethnic balance as a matter of national policy. It’s pretty much an open secret that Singapore lets in a proportionate number of Chinese from China, Indians from India, and Malays from Malaysia. In 2013, Grace Fu, then Minister in the Prime Minister’s Office, publicly confirmed that Singapore’s immigration intake was explicitly designed to preserve the city-state’s longstanding ethnic ratios:

It is our policy to maintain the ethnic balance in the citizen population as far as possible… We recognize the need to maintain the racial balance in Singapore’s population in order to preserve social stability. The pace and profile of our immigration intake have been calibrated to preserve this racial balance. (Straits Times, February 5, 2013).

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong (2004-2024) reiterated the same position just days later, stating:

We will preserve the Singapore character of our society. In particular, we will maintain the ethnic balance of our citizen population. (Straits Times, February 9, 2013).

As early as 2009, Lee Kuan Yew had already noted the necessity of ‘carefully controlling’ the intake of Permanent Residents and new citizens in order to ‘keep the character and values of Singapore society.’ That policy is still in place. Despite Malays having a fertility rate that is nearly double that of the Chinese and Indians, the ethnic balance has thus hardly shifted in decades. This is no accident. And the effect is compounded by the fact that many skilled workers from Malaysia and Indonesia who are absorbed into Singapore are ethnically Chinese themselves.

It goes without saying that all racial groups in Singapore have equal legal rights. But a few details tell a more nuanced story. While it is a myth that Malays are formally barred from serving in the Singapore Air Force, in practice, their representation — especially in sensitive roles such as pilots or positions involving advanced weapons systems — has historically been limited. This restriction is widely believed to have stemmed from Singapore’s past wartime contingency plans against Malaysia, which centred on a rapid blitzkrieg into Johor when relations were cold in the ’60s and ’70s. This was confirmed by then Second Minister of Defence (and son of Lee Kuan Yew) Lee Hsien Loong, who stated that they did not want to put Malays in a ‘difficult position’ where their loyalties to religion and nation are in conflict. However, the situation has changed significantly since then, and it’s less likely such precautions are taken nowadays.

If Costin Alamariu is right in dubbing Singapore a ‘Chinese ethnostate’, it is nonetheless an ethnostate that gives significant concessions to its minority groups. Every GRC (Group Representation Constituency, Singapore’s electoral innovation where at least one MP must be a minority) ensures Malay or Indian representation, although a cynic would argue that these candidates are only there to pacify minority groups. In 2017, a presidential election was reserved exclusively for Malays, much to the chagrin of some Chinese Singaporeans, resulting in a walkover victory for an innocuous old Malay lady, President Halimah Yacob (2017-2023). Again, a cynic might — rightly or wrongly — say that this was done to block a Chinese anti-PAP rival, Tan Cheng Bock. The state supports Islamic law for family matters, which notably allows legal polygamy for Muslim men. Cultural grants, heritage preservation, and public acknowledgment of Malays as the region’s ‘native people’ are standard. And yet, there is no parallel society: racial quotas were implemented for the three main ethnic groups in public housing, a policy that doesn’t seem to have led to much interracial strife; a genuinely peaceful, even if not blissful, coexistence.* Unlike many Western states, Singapore has achieved genuine multicultural harmony without ghettoisation. The state seems to be equally as concerned, believe it or not, with ‘white supremacism’ among its Chinese population than it is with Islamic fundamentalism among its Malay population.

(* Some have argued — in my opinion, wrongly — that the public housing racial quota was another dastardly PAP ploy to spread the non-Chinese vote out, which would ensure electoral dominance by gerrymandering the first-past-the-post voting system. In my opinion, doing so would come back to bite them in the future, if a small swing were to cause several marginal seats to be lost. The concentrated ethnic minority urban vote for Labour up to now demonstrates this problem, with many votes being ‘wasted’. I think Lee Kuan Yew was far-sighted enough to see that this would eventually come to pass.)

Malay interracial friendships remain rare, however, whereas Chinese-Indian friendships and romantic relationships are growing (albeit with disapproval from some Chinese in the older generation). Yet Malays seem content. Besides their quite placid temperament, it seems that the shared economic success of Singapore has played a significant role in this.

The Indian Dilemma

Indian migration to Singapore followed a parallel arc to that of the Malays and Chinese, but with a sharper class gradient. Two primary waves stand out. The first, between 1825 and 1873, comprised convict labourers and low-caste ‘coolies’ (indentured labourers) brought in under British rule. Many remained in Singapore upon release, forming a working-class Tamil substratum — the bedrock of Singapore’s Indian community. The second wave was altogether different: a highly educated stream of clerks, administrators, and bureaucrats, including Ceylonese Tamils appointed to staff colonial institutions by the British. Their descendants still occupy visible positions in Singapore’s intellectual and political life: from S. Rajaratnam, a founding father and Lee Kuan Yew’s sole original South Asian cabinet member, to the current President, Tharman Shanmugaratnam (2023-).

Despite being a small minority, Indians have thus long punched above their demographic weight in terms of prestige, visibility, and institutional influence. Yet, like their counterparts in the West, they have faced severe reputational damage due to recent immigration from the Indian mainland. This new wave has triggered a discernable ‘vibe-shift’, although not quite on the same level as Canada and Britain (largely owing to the guest worker dormitories being located in the remote outskirts of the city, discussed in my previous article). Nonetheless, a tourist dropped blindfolded into Little India on a Sunday could be forgiven for thinking they’d landed in Chennai. Meanwhile, Bukit Batok on the west side of the island functions as a more subdued, bourgeois middle-class satellite, but is still distinctly Indian in character.

Indian immigration is easily the most contentious of Singapore’s immigration streams. The primary source of resentment is CECA: the Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement, signed between India and Singapore in 2005, and renewed in 2018. In theory, CECA was a standard bilateral trade pact. But in practice, it became another typical Indian emigration and remittance mill, especially in the IT and finance sectors, where the Indian stereotype of ethnic nepotism has been advanced by opponents of the treaty. The result is that ‘CECA’ is now a metonym — and slur — for any Indian migrant who is seen to behave rudely, anything from playing Indian music loudly in the bus to leering at young women. Far cruder Hokkien or Malay terms circulate, of course, but they are best not repeated here.

So acute is the public backlash that at least three opposition parties — including the middle-ground, social-democratic Progress Singapore Party (PSP) — have explicitly called for CECA to be reviewed or revoked altogether. In 2020, Leong Mun Wai, a PSP MP, remarked in Parliament how ‘deeply disappointed’ he was that DBS Bank, the biggest Singaporean bank, did not have a ‘home-grown’ Singaporean CEO, after Piyush Gupta, an Indian national, was appointed, possibly making him a beneficiary of CECA. Two government ministers, S. Iswaran (an Indian-born MP later convicted of accepting gifts worth nearly $400,000 over a period of many years) and Ong Ye Kung (a former leadership hopeful), accused him of racism. Unlike in Britain, where the ‘Boriswave’ of Indian migration is viewed with unease and anger but little structural understanding other than blaming Priti Patel for ethnic nepotism (not a wholly unfair assumption, but also not the real cause), a surprising number of the largely apolitical Singaporean public grasps the direct causal link between CECA and the Indian presence, making the political class somewhat more accountable for its second-order effects.

A flashpoint of poor relations actually occurred much earlier, before CECA-related concerns were as widespread, in 2013. That year, a Chinese bus driver accidentally ran over and killed an Indian guest worker. The result was the worst public race riot in decades, erupting spontaneously in Little India. The government’s response was hilarious, indicative of both its attempts to remove blame from Indians while also reinforcing stereotypes. What did the Singaporean state do? It blamed alcohol. An early alcohol sales ban in the entire Little India precinct was thus put in place, cutting off supply at 7pm — or 3.5 hours earlier than the 10:30pm national limit. It was designated a ‘Liquor Control Zone’, along with Geylang, a popular nightlife district in the east. It’s not unreasonable to suspect that they put the same prohibition on Geylang purely to make the racial targeting seem less blatant (and if so, they failed).

While in the West this would be viewed as a racially-targeted infringement on civil liberty, in Singapore it passed with little fanfare. It was broadly accepted as a common-sense response to a visibly rowdy weekend culture (anyone who has passed through Little India on a Sunday evening can attest to the number of drunk Indian men carrying 8%+ ‘Knockout Lager’ in their hands). One could, with a flair at English Literature GCSE-style thinking, could interpret this alcohol ban as a demonstration of sovereign control; a performative reminder of who runs the show. And perhaps it was. But what is most striking is not the ban itself, but how little was made of it by the public.

A Chinese Ethnostate?

The Chinese population arrived in several waves from the early nineteenth century onwards, first in the form of indentured labourers, and later as merchants and craftsmen. Many were Hokkien, Teochew, Hakka, and Cantonese, fleeing overpopulation, famine and the collapse of the Qing order; or drawn by the economic opportunities of tin mining and urban construction, recruited labour rather than organic migration. The British actively encouraged Chinese migration to fuel Singapore’s rise as an entrepôt colony. By the early twentieth century, Chinese settlers formed the majority of the population, a demographic dominance they have retained to this day.

A common misconception is that the Singaporean Chinese must identify strongly with their race and thus with the People’s Republic of China. This could hardly be further from the truth. This goes beyond the basic fact that Mainland Chinese migrants are usually not from the same Chinese subgroups as the Singaporean Chinese, thus being inherently ‘different’. Below Indians and Bangladeshis, the most commonly complained about immigrant group is not white expats (ang moh, lit. ‘redheads’), nor the thousands of South East Asians who come to work as housemaids, but Chinese blue collar immigrants (so-called ‘PRCs’), who can sometimes be seen as uncouth.

Yet it’s important to distinguish this type of PRC migrant — often working class, with poor social integration — from a very different demographic of Chinese newcomers whose presence is less publicly resented, but arguably more consequential: the early-career white-collar class. This type of migration cannot be fully understood without appreciating the country’s long-standing foreign talent strategy, a national policy cultivated and promoted at the highest levels of government since the ’80s. Then-Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong (1990-2004) — calling him Singapore’s John Major would be harsh, although he did succeed after Margaret Thatcher, our Lee Kuan Yew, and they look like transracial cousins — made this explicit in his 1997 and 1999 National Day Rally speeches, where he announced the ‘Foreign Talent Policy’, and stated unequivocally: ‘It is talent that counts. We can be neither a first-world economy nor a world-class home without talent. We have to supplement our talent from abroad.’

This logic was reiterated a decade later by Lee Kuan Yew, who warned that Singapore’s plummeting fertility rates (well below the 2.1 replacement rate) would necessitate a continual inflow of ‘able, young and energetic immigrants from China, India and Southeast Asia’ to sustain the country’s vitality. The result was a concerted, multi-tiered strategy to draw foreign-born individuals at every stratum of the labour market — from CEOs and scientists to skilled technicians and bus drivers.

What this policy looks like in practice, however, is seemingly more random. While many Chinese migrants do arrive through the expected professional and technical channels — engineers, IT workers, established academics — a significant proportion occupy what might fairly be described as lower-middle class ‘luxury’ jobs that only exist in a highly developed economy; the sort of jobs one would assume would be preferentially given to local Singaporeans, particularly in marketing, event management, and other ‘soft’ white-collar occupations. Arguments of ‘meritocracy’ to justify such migration are nebulous when one considers that it is very difficult to meritocratically decide between candidates for such a weakly g-loaded and ‘soft’ job as an entry-level marketing employee.

Such unnecessary competition from both Indians and Chinese has caused significant disquiet among locals, and is one one the reasons why the PAP did so historically badly in the 2011 General Election, after which net migration significantly tightened year-by-year in the build-up to the COVID period. Where once it took just a few years of residence to obtain Permanent Residency (PR), that figure has now stretched to well over fifteen years for many, depending on a range of factors involving nationality (Chinese, Indians, and Malaysians are most preferred), race, income, educational background, age, and other factors like whether one has a Singaporean spouse or children. In effect, citizenship has become a long-haul prize, awarded not simply for presence or paperwork but for perceived integration and contribution. The system is famously opaque, and this seems to be intentional. Unlike Britain, which runs on the logic of legal entitlement and technicalities, which inevitably invites disputation and appeals tribunals, Singapore makes no apology for its discretion. There is no automatic right to residency, and the state can reject your application for PR status numerous times without giving a single reason.

This shift coincided with a series of increasingly stringent foreign manpower policies. One of the most salient examples is the Dependency Ratio Ceiling (DRC), which limits the proportion of foreign workers a firm may employ. In the services sector, this cap is set at 35% (down from 38% a couple of years ago), far tighter than in construction (87.5%), manufacturing (60%), or the marine shipyard sector (77.8%). In essence, this is a system that recognises the need for foreign labour in certain physically or technically demanding sectors, but simultaneously protects Singaporean access to ‘soft’, customer-facing, and white-collar roles. These are precisely the kinds of jobs that, in Britain, are increasingly filled by non-citizens with minimal barriers or scrutiny — marketing assistants, HR officers, local government clerks — often justified under the vague banner of ‘diversity’, but in practice representing a silent displacement of native graduates for no obvious reason at all. Increasingly, even British medical trainees are being displaced, which is totally absurd, given the obviously lower ability of doctors who trained in Third World countries.

Furthermore, Singapore has wage floors and levies for hiring foreign workers to create financial disincentives that compel firms to justify foreign hires in real economic terms. Foreigners must be paid above a minimum threshold (S$3150 (≈£1,825) for S Pass holders and S$5600 (≈£3,250) for higher-skilled E Pass holders), and employers must pay monthly levies that increase with each additional foreigner employed (now S$650 (≈£650) per month for S Pass holders). In Britain, by contrast, no such pressure exists; instead, public and private sector employers are actively subsidised for ‘diversity hires’, even when they have fewer qualifications or worse English. In Singapore, hiring a foreigner is a business decision with clear and measurable cost, which the government can (and will) adjust depending the circumstances. By contrast, the British system has become a humanitarian sieve, shaped more by sentiment and byzantine legalism than strategy. Whereas Singapore actively blocks foreigners from accessing subsidised public services and engineers long delays before PR or citizenship is granted, Britain offers nearly instant access to public services and an accelerated path to citizenship for nearly anyone who lands on its shores. The result is that Singapore has made the white-collar job market more competitive and well-paid for its own people, while Britain has actively destroyed its middle class.

Alongside this is a more meritocratic, but still mysterious category of PRC migrant: the Chinese postgraduate student and early-stage academic. By the early ’00s, Chinese nationals had come to form the largest share of Singapore’s foreign academic workforce. At National University of Singapore (NUS, Singapore’s most prestigious university) in 2001, out of 1,671 full-time teaching staff, nearly 47% were foreign nationals, 14% of them Chinese. Among full-time researchers, that proportion was even starker: 73.7% were foreigners, and 39% of those were Chinese nationals, and that figure has almost certainly increased since then. It appears that student visa pathways are increasingly used as de facto immigration channels, particularly for Chinese nationals entering graduate or doctoral programmes. I’ve never seen such a huge gulf between industry uptake by foreigners versus locals in any country or any industry, other than perhaps the English Premier League.

Why fund a foreigner’s degree, during the least productive time of their academic lives, if you don’t expect them to stay on? Why are they doing subjects that possess little obvious economic, public policy, or cultural value? Many of these postgraduates and researchers are awarded stipends that approximate a monthly salary of between S$3,000 (≈£1,750) and S$4,000 (≈£2,300) — not an enormous sum in Singapore, but effectively a living wage to pursue higher degrees in highly intangible or non-productive fields like marketing or the humanities. Their academic output, while not necessarily wholly without merit, possesses limited domestic applicability, raising the question of what tangible benefit is being gained in exchange for their fully subsidised residence.

Unlike employment pass holders or PR applicants, international PhD students face no racial or national quotas, and once embedded within university systems, they can transition to longer-term residency through existing talent pathways. Maybe the answer lies here. While they can presumably write academic English fairly competently, their English speaking ability leaves a lot to be desired, yet somehow they reach the minimum required level to enter an English-speaking country. The reader is presumably familiar with the phenomenon of barely-fluent Chinese postgraduate students in their own universities, as they are a reliable cash-cow for largely undeserving British academia, and Singapore is not immune to this problem either.

Given that PhD students and young researchers are an obvious financial liability in a country not known for such laxity, one is forced to wonder if there are hidden motives behind this policy. It appears that the apparent ‘neutrality’ of academia thus becomes a convenient means of importing a coterie of smart young Chinese folk, since they can integrate well after just one generation and boost the Chinese share of the population (which has been marginally declining since the ’80s). It’s also tempting to speculate that such talent-import policies double as a form of gene pool maintenance given the decent IQ levels of such foreign imports — though such thoughts are of course unmentionable in polite company (that said, a good number of Chinese Singaporeans would gamefully entertain the thought). One wonders if such a backdoor solution results from Lee Kuan Yew’s failure to implement eugenic policies in the 1980s onwards. Alternatively, it may reflect bureaucratic capture and the relentless quest for university rankings. Or, most simply, the academic route is too poorly paid — especially after two years of National Service — to attract top (male) Singaporean graduates. Regardless, many Chinese parents have caught onto this; there are apocryphal stories of droves of Chinese parents coming on holiday to Singapore specifically to show their children NUS or NTU (Nanyang Technical University, Singapore’s second best university), and tell them that they must attend this university.

Part 2, discussing Singaporean multicultural policies in more detail, and explaining why such policies are almost guaranteed not to work in Britain, will be published next week.

This article was written by Harry Yew, a Pimlico Journal contributor who lives and works in Singapore. Have a pitch? Send it to pimlicojournal@substack.com.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing. If you are already subscribed, why not upgrade to a paid subscription?

Came across this piece on X, unfortunately through a groyper account run by an individual who would be deported from Singapore (funny they don’t realise that and think it’s a dark enlightenment Mecca). It’s an informative essay with novel observations that could’ve only come from an outsider, because Singaporeans are famously reluctant to publicly opine on matters of race and religion, but I would like to correct some inaccuracies below. I trust that my comment will see the light of the day in the spirit of the pro-truth and anti-censorship ideological bent of this publication.

1. The Little India riot in 2013 was not, as the author put it, a ‘race riot’. The author might be desensitised to the magnitude of the term in Singapore because of the ubiquity of communal disturbances in his homeland, but in modern Singapore, a race riot is the equivalent of a black swan event. The Maria Hertogh riots and the Chinese-Malay clashes of 1964 and 1969 were the last communal riots to have afflicted Singapore, and these occured amidst the backdrop of merger and separation from Malaysia. The foreign workers who rioted in Little India were inebriated boors frustrated by their lot in life, not pogrom participants seeking to lynch out-groups on sight.

2. The author made a critical error of judgement by using Indian immigration to the likes of Canada as an analogy for Singapore’s immigration dynamics. Perhaps the comparison was necessary to contextualise things for a Western audience, but there’s a better analogy. Old-stock ethnic Indians in Singapore are more akin to the Québécois by way of their nature as a foundational ethnic minority group. New-stock Indian immigrants are certainly not part of the core demos, but their presence is a second-order effect of the government’s insistence on keeping the prevailing C-M-I-O ethnic mix static. The fresh-off-the-boat Indians are a necessary counterweight to the mass importation of ethnic Chinese FOBs to the tune of millions. Without this foil, Singapore would become a Chinese settler-ethnostate within a decade, with their percentage of the population eclipsing 80%, and the “Israel of Southeast Asia” allegations from Sinophobic Malaysian and Indonesian Islamists would dominate the national psyches of Singapore’s neighbouring nations. This would spell trouble for the country.

3. To reiterate, this is in no way analogous to the situation in Canada or other Western countries. Claiming that Indian immigration to Singapore has resulted in ‘reputational damage’ to old-stock Singaporean Indians is as asinine as making the same claim for the PRCs vis-a-vis old-stock Singaporean Chinese, and there are a lot more of the latter around. I don’t begrudge the author, who is a racial outsider, for lacking familiarity with how Singaporeans self-identify, but Singaporeans are pretty good at spotting other Singaporeans of different racial backgrounds and treating them accordingly. There are certain visual and behavioural tells that the author simply isn’t privy to. The author may seem them as generic ‘Chinese’, ‘Malays’, and ‘Indians’, but these groups have had centuries of familiarity with each other and have collectively assimilated to a common civic identity. Not to mention the common accent.

4. For someone who admires Singapore and the system of governance that keeps it exceptional and an oasis of tranquility the author is surprisingly blasé about the importance of adopting stringent penalties against the communalisation of politics. The author’s insinuation that the allegations of racism against Singapore’s marginal opposition politicians (who are dyed in the wool Chinese chauvinists, the sort LKY sought to eliminate) were frivolous is not only without merit (because, as mentioned above, Indian immigration is a second-order effect of Chinese immigration) it leaves the door open to Western-style communal strife that would decimate the country from within. Should Singaporean MPs be allowed to discuss the Israel-Palestine affair at length, perhaps even issue condemnations of either entity? No, and for good reason, because it’s radicalising Malay Singaporean youth as we speak. Most Singaporeans accept the soft-authoritarian curbing of their FoE privileges. There is no room for majoritarianism AND minority grievance-mongering in Singapore. Anyone who seeks to excuse one or the other is no friend of the country or its people.

5. Lee is the surname, not Yew.

"although East Asians have a higher average IQ than Europeans, the distribution tends to cluster around the mean".

There's no good evidence for this AFAIK and this seems to be a misconception. The standard deviation of East Asian countries on the PISA tests are just the same as in Western countries. So, the East Asian distribution is not narrower.

The American IQ standard deviation may be wider than that of e.g. Japan, but that would in the first place be because the US is a more diverse country with large racial minorities with different IQ distributions. Lynn and Hampson (1986) said so themselves: "Japan does not have the range of racial minorities that are present in the U.S. and increase the heterogeneity of the American population. The greater homogeneity in Japan is shown by the lower standard deviations on the McCarthy scales, where the Japanese standard deviations are approximately 85% of those in the U.S." (https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-2896(86)90026-7)

"Malay criminality centres around what might be called ‘market crime’ [...] This type of crime is not primarily violent"

Is there any stats that you could refer to? Groups that are overrepresented in crime tend generally to be overrepresented in all types of crime, and nonviolent crimes generally constitute a large proportion of crimes in all groups. I suspect that even if much of Malay criminality is nonviolent, there should still be a difference between Malays and Chinese when comparing violent crime rates.