MPs are almost certainly using ChatGPT to generate Commons speeches

A statistical analysis, and some tell-tale signs

‘As he looked round upon the House and perceived that everything was dim before him, that all his original awe of the House had returned, and with it a present quaking fear that made him feel the pulsations of his own heart, he became painfully aware that the task he had prepared for himself was too great. He should, on this the occasion of his rising to his maiden legs, have either prepared for himself a short general speech, which could indeed have done little for his credit in the House, but which might have served to carry off the novelty of the thing, and have introduced him to the sound of his own voice within those walls,—or he should have trusted to what his wit and spirit would produce for him on the spur of the moment, and not have burdened himself with a huge exercise of memory.’

In Trollope’s best political novel, Phineas Finn, the eponymous hero (a sensitive young man avant la lettre) is so overwhelmed by the majesty of Parliament and the dangers that a poor maiden speech is fraught with that he waits for over a year to make it. This was an era in which the decisions of Parliament made really mattered, and a good first speech marked you out as a ‘coming man’. It was a raucous House of Commons with a much weaker party whipping system, where oratorical skills and a genius for argument could genuinely swing a vote.

Compare this, then, to what we suspect is occurring today: MPs outsourcing their own thinking to artificial intelligence in a system where almost everything is pre-arranged theatre.

I. The statistical evidence for believing that MPs are regularly using ChatGPT to generate Commons speeches

In mid-August, The Mirror published a story about Mike Reader, the newly-elected Labour MP for Northampton South, being spotted using ChatGPT to respond to constituents’ letters while working on a train. This provoked discussion on whether MPs should be using AI for this type of routine task, with most of the concerns raised touching on privacy issues and laziness. Subsequently, Reader wrote a pretty reasonable opinion piece in PoliticsHome defending his use of ChatGPT — and I would be curious to find out more about which Tory MPs refuse to respond to emails because of GDPR, as Reader claims — by pointing out that lots of the correspondence they receive is extremely boilerplate and would have received a generic response even in the days before LLMs. I do not wish to make a grovelling defence of MPs — ‘Don’t you know they’re SO busy and important, do you really expect them to take notice of YOU?’ — in the slavish manner of many former parliamentary assistants, but ultimately, it is hard to be particularly bothered about AI being used in this way (especially when we consider that many of these ‘letters’ were in fact directly copied from campaign websites, and a ChatGPT response is still considerably more effort out from the MP and/or their team than was put in by the constituent).

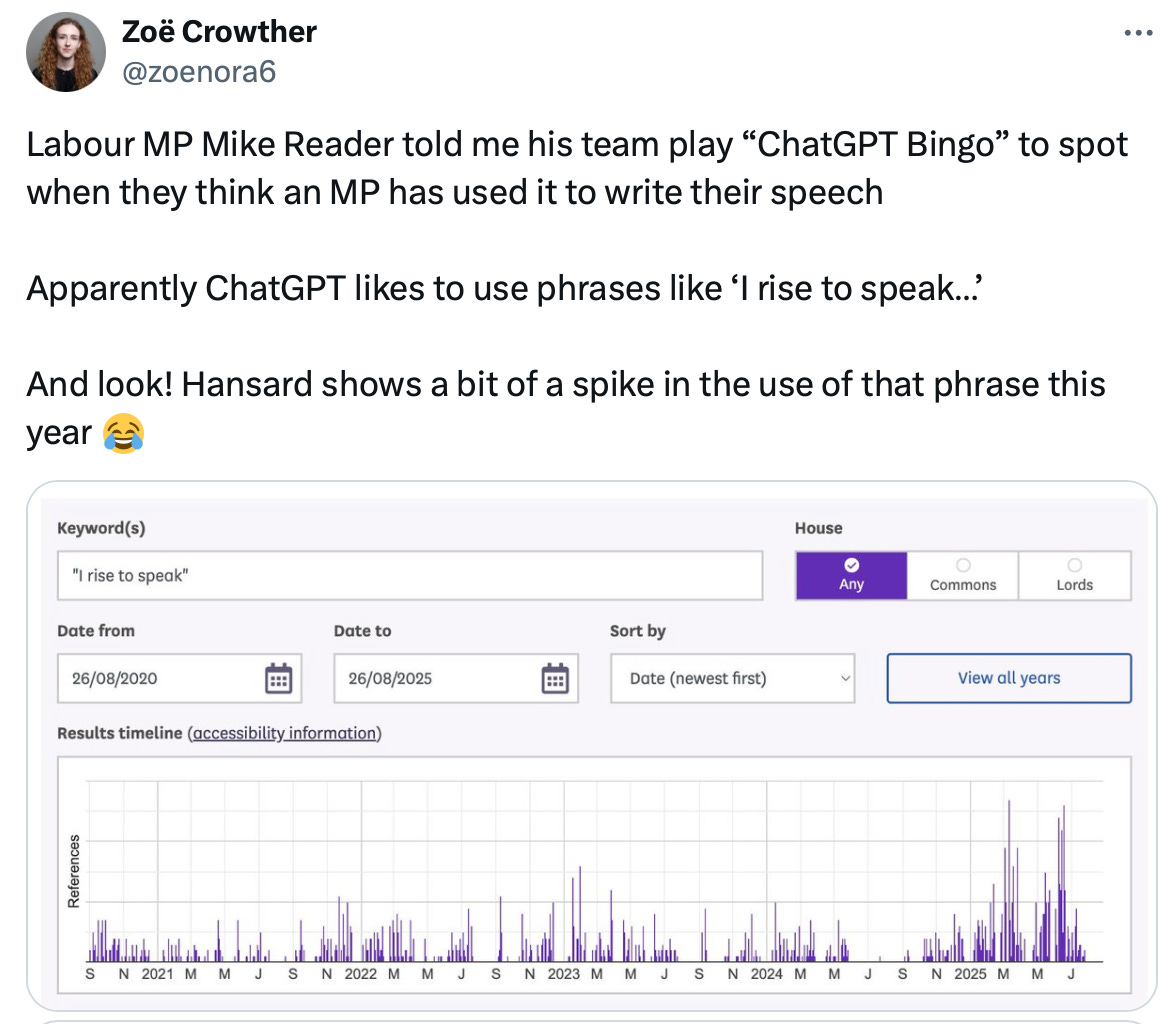

What would be far more egregious and alarming is the use of AI to write parliamentary speeches. Zoe Crowther of PoliticsHome posted a chart showing a recent spike in the frequency of the phrase ‘I rise to speak’ in Hansard after being tipped off by Reader that this is a tell-tale sign of ChatGPT.

This spurred further debate, with The Times publishing an editorial on Friday with a similar view to my own: sometimes acceptable if responding to emails, not so much if being used in Parliament. The editorial ended with the question: ‘What cruel news channel will it be that splices together examples of this synthetic oratory?’

Pimlico Journal is not a news channel, but we hope to be able to rise to this challenge nonetheless. In order to do so, we will start by looking for further statistical indications that AI is being used to generate speeches in Parliament. After all, ‘I rise to speak’ is just one phrase, and with a large crop of fresh MPs, it is not outside the realms of possibility that the phrase just caught on through a sort of social contagion because newcomers thought it was somehow ‘the done thing’.

Identifying AI-generated speeches is not an exact science. The most obvious giveaways of AI usage generally fall into the category of ‘you know it when you see it’, rather than being definable as a search term in Hansard. By this, I mean patterns such as an obsession with ‘the rule of 3’, the use of the broad ‘it’s not [X], it’s [Y]’ format (which has several derivatives), adding needless asides that would be obvious in the context of the speech, and overly-dramatic short statements that just seem out of place. We have to use specific words or phrases to generate the data, and this has the obvious limitation of missing out on some of those more general tell-tale signs.

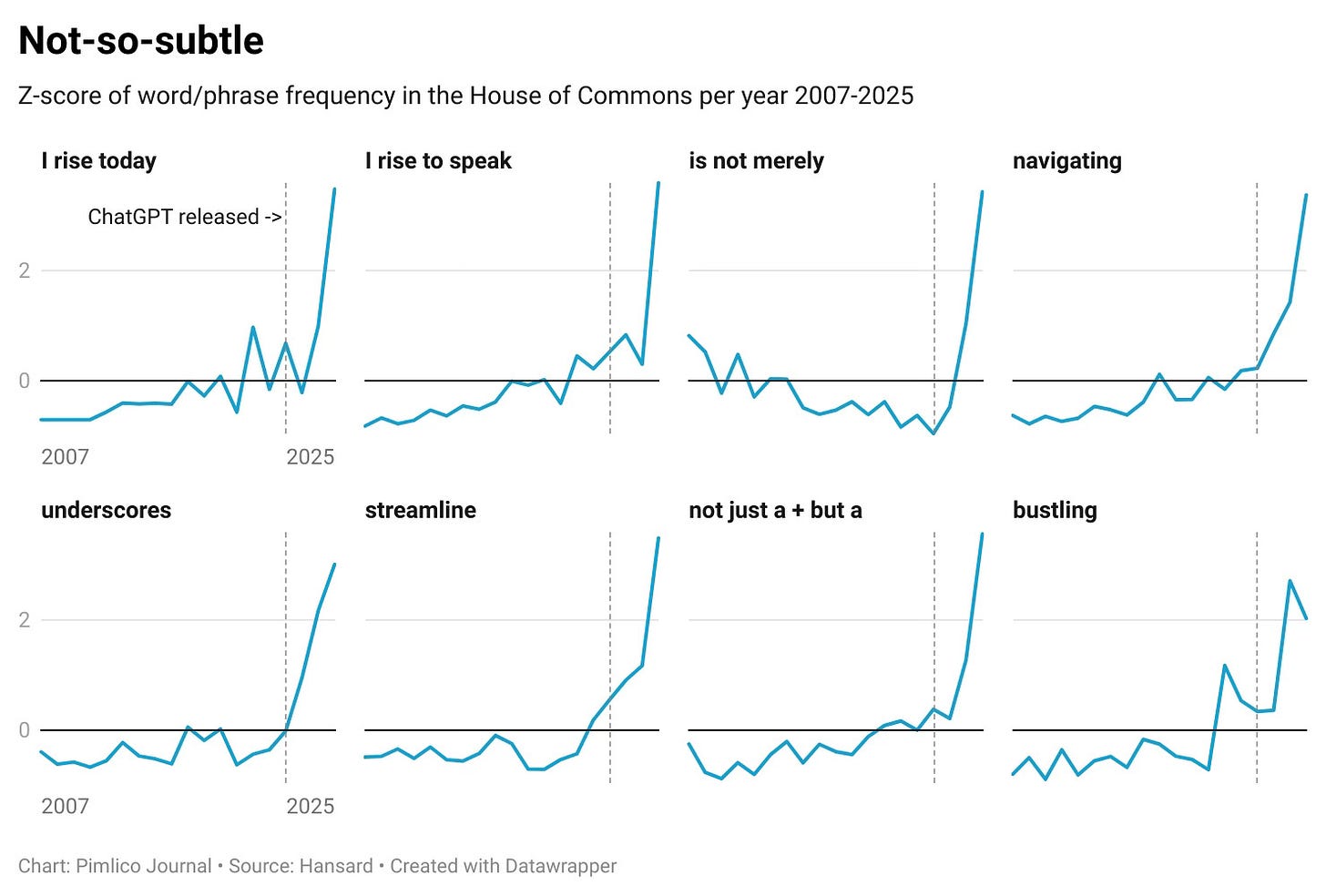

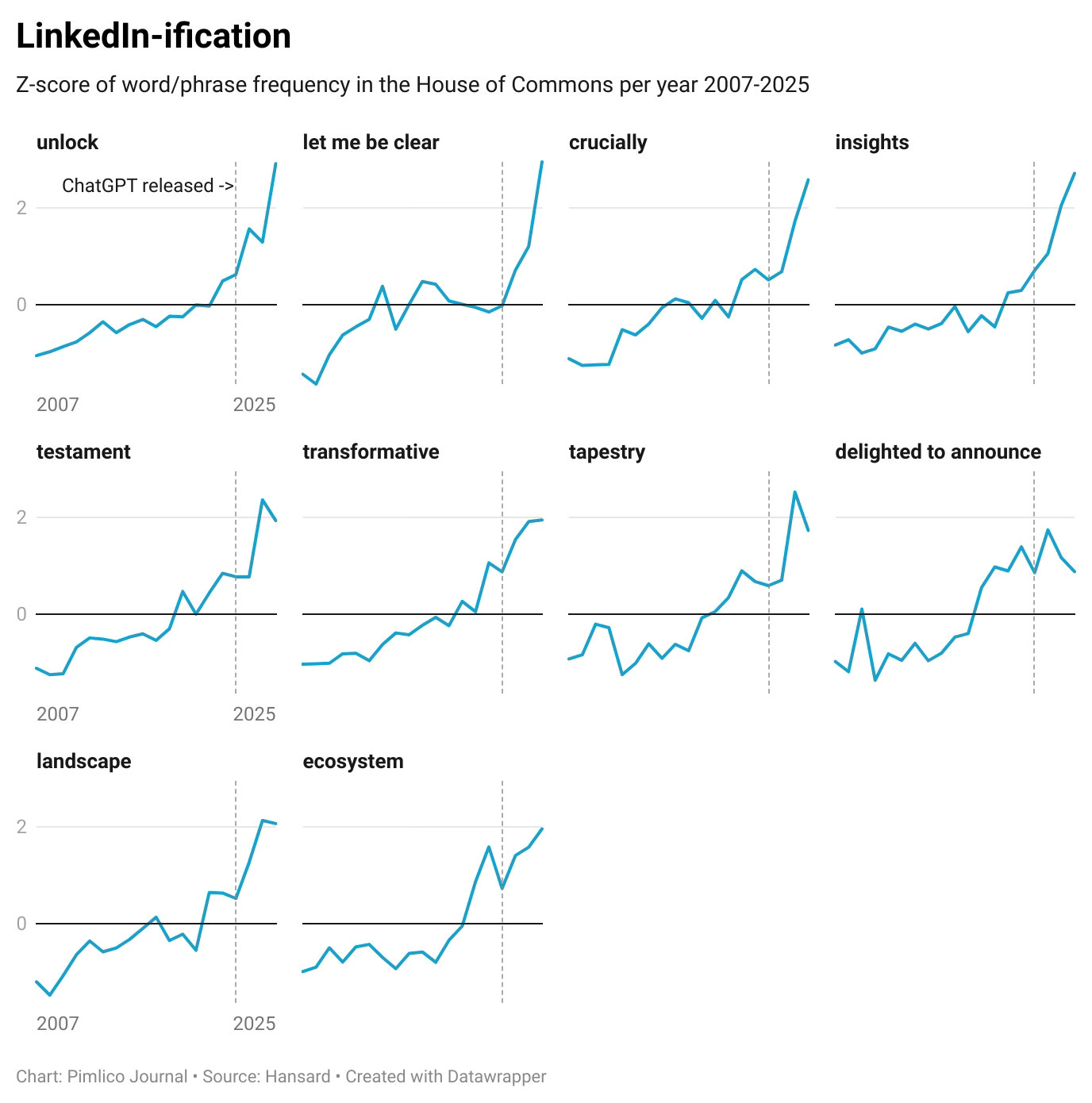

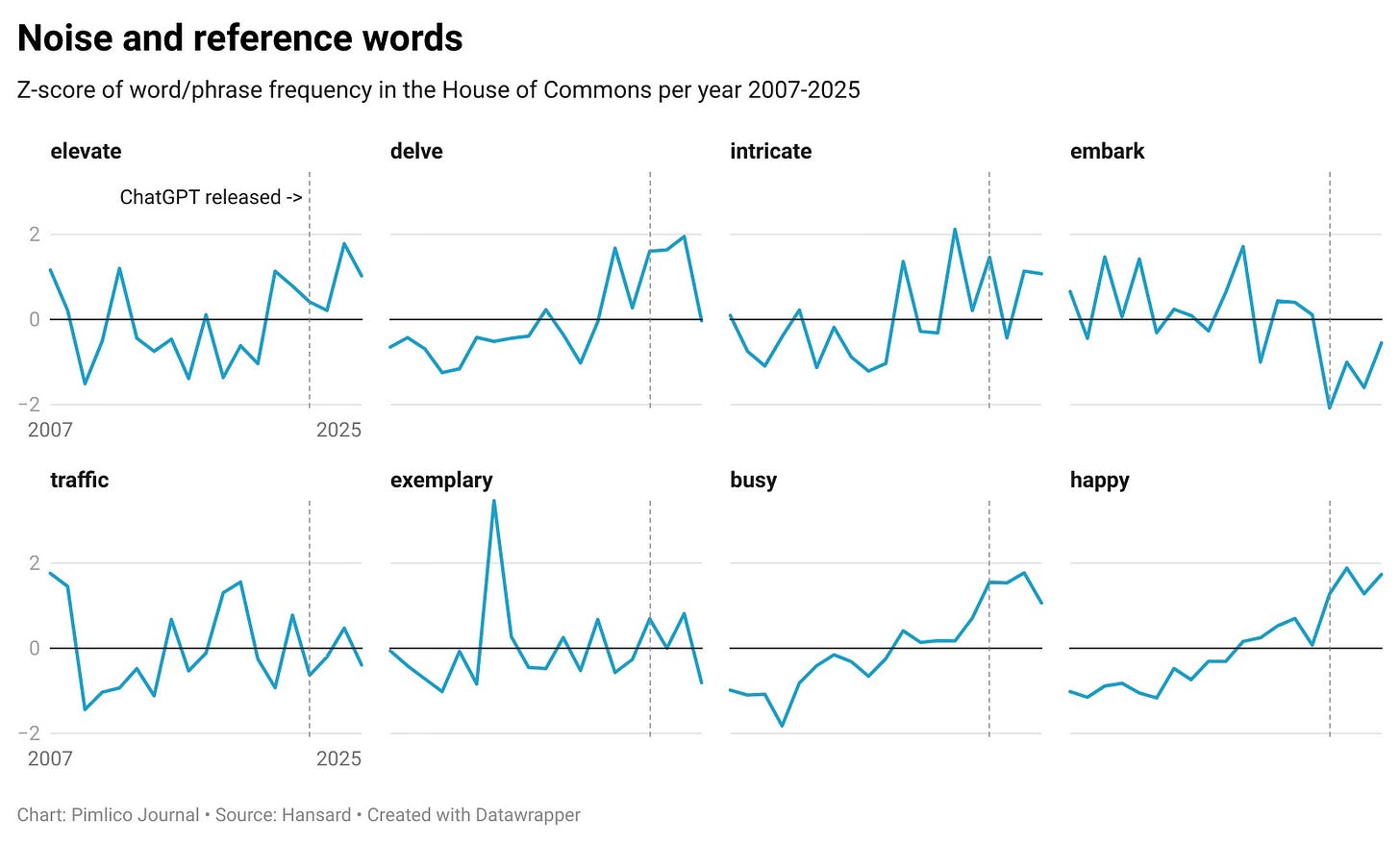

The following search terms were sourced by browsing articles and online discussions on what words and phrases AI-generated text overuses, as well as my own experience (some of these words, despite often being cited as disproportionately frequent in AI-generated text, have been excluded for reasons that are listed in Appendix A). Below, you’ll find a series of graphs showing the Z-score — a measure of how far a value in a set is from the mean, expressed in units of the standard deviation — of the frequency of AI-associated words and phrases, as well as some reference words, in the House of Commons each year from 2007 to 2025. The frequencies of the word or phrase in each year were adjusted by a factor (Appendix B) that attempted to measure how many words were spoken in total in Parliament in that year: for instance, 2025 is adjusted upwards because there have been fewer words spoken in the eight months of the year so far compared to most full years.

These are eight words or phrases which are all associated with AI-generated text, and have all seen recent, otherwise seemingly inexplicable, spikes in popularity. I think that this is very likely due to the use of AI to write parliamentary speeches.

Here are ten more words and phrases which are also associated with AI-generated text, but have shown a more gradual increase in usage since 2007 before accelerating (in almost all cases) from 2022, rather than just a sudden spike in the last couple of years. This can help us make a broader point about the sort of language that AI uses. I would call this ‘LinkedIn-ification’: today, more and more content on the internet is written in a sterile and formulaic vernacular of buzzwords, and this filters through into real life; presumably, lots of this text was used as AI training data. This can explain the aforementioned general pattern: an increase since 2007, as this vernacular slowly but steadily became more widespread, and then an acceleration after the release of ChatGPT in late 2022. I would, however, be rather less confident in stating that the increase in usage since 2022 is because of AI, though I still think it is highly likely, especially for the first four words. (I’ve also included ‘landscape’ and ‘ecosystem’ as two AI-associated words that also have reason to be used heavily in parliamentary debates.)

The top row contains four well-known ChatGPT favourites which don’t show any obvious AI-related pattern (potential reasons for this are given in Appendix C). The bottom row contains some reference words. As an interesting aside, the huge spike in the use of ‘exemplary’ in 2013 is because of one single day of debate on 18 March about the Crime and Courts Bill where the specific phrase ‘exemplary damages’ is used over and over again. This huge outlier has a Z-score of 3.48, which is still smaller than the 2025 Z-score for ‘I rise to speak’ of 3.60!

II. Some actual examples of Commons speeches that we have reason to suspect might have been generated by ChatGPT

We have hopefully provided sufficient statistical evidence to convince readers that we have good reason to suspect that AI is regularly being used to write Commons speeches (or at least regularly enough to cause some otherwise inexplicable shifts in word usage). But to really see how this might manifest in practice, we should take a look at a potentially suspicious speech. In particular, we will look at a speech that was flagged as having the ‘not just a [X], but a [Y]’ format (perhaps the most well-known verbal tic of ChatGPT).

The speech below, reproduced with my comments, is by Wendy Morton, the Conservative MP for Aldridge-Brownhills since 2015 (and a Shadow Minister for Foreign Affairs since November 2024). It is from a debate about forcibly deported Ukrainian children. In fact, this speech was only tagged once in my automated search for the ‘not just a [X], but a [Y]’ term, which shows how tricky it is to capture the full extent of AI-associated phrasing. We should be absolutely clear that we have no definitive proof that this speech was written either entirely or to a large extent by AI, but the sheer quantity of AI-associated tics is startling:

Few crimes are as harrowing or telling as the theft of a child, but that is what we are debating today: the forced abduction, deportation and ideological reprogramming [rule of 3] of Ukrainian children by the Russian state. We need to call it out for what it is. It is not a relocation or an evacuation, which the Kremlin may dress it up as, but a systemic, state-sponsored assault [not just, but] on identity, sovereignty and humanity itself [rule of 3].

Since Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, more than 19,500 Ukrainian children are known to have been forcibly removed from their home and transferred across Russian-occupied territory into Russia itself. Independent estimates suggest that the true figure could be more than double that. As we have heard today, with each child taken, we see families torn apart, culture erased and the future of a nation under threat [rule of 3]. Behind every number or statistic is a child, a family, friends and loved ones [rule of 3].

I want to make three points. First, Russia’s actions are not just indefensible, but calculated, deliberate and disgraceful [not just, but] [rule of 3] [a strangely redundant choice of words — is it really necessary to add that it is ‘disgraceful’ here, and surely it is odd to start with the fact that it is ‘indefensible’?]. Secondly, during our time in government, the Conservatives led the way not just with weapons and sanctions but with unwavering moral clarity [not just, but] and practical action in support of Ukraine. Thirdly, I urge the Government to be clear-eyed and bold. They should build on what we started and not flinch in the face of Putin’s cruelty.

I have had the privilege of visiting Ukraine twice: once as a Foreign Minister in 2021, and again in 2023 as a Back Bencher with the Westminster Foundation for Democracy. On my first visit, I stood alongside Ukrainian leaders at the launch of the Crimea Platform, which was a powerful signal of international solidarity. Even then, Russia’s creeping aggression in Donbas and Crimea cast a long shadow, but the spirit of the Ukrainian people shone through. [This paragraph lacks any of the most obvious signs suggesting ChatGPT usage; interestingly, unlike most of the rest of the speech, it also actually contains something specific to the speaker herself. This may suggest that this paragraph was written without the use of AI.]

When I returned two years later, though, Ukraine was in the grip of war as a result of Putin’s illegal invasion. Towns were scarred by missile strikes, civilians were forced underground and families were scattered across borders [rule of 3], but what struck me most was the resilience of the people I met: parliamentarians who had lost colleagues, mothers who had sent their sons to the frontline, children who were being educated in bunkers at school, and civil society leaders who were rebuilding community life amid chaos. They were resisting not just an illegal military invasion, but an assault on their identity, their history and, as we have heard clearly today, their children [not just, but] [rule of 3].

That is why the forced deportation of Ukrainian children is such a grotesque element of this war—it is wrong [Very strange phrasing here. ‘That is why’ presumably refers to the previous paragraph, but I fail to see how that paragraph has any bearing on the morality of child abduction. The added statement (‘it is wrong’) at the end is here is even more bizarre and sticks out. Something is ‘grotesque’ because ‘it is wrong’? A human would normally present the reasoning the other way around]. These are not isolated incidents; they are part of a strategy [not just, but] to wipe out the next generation of Ukrainians by forcibly assimilating them into Russia—renaming them, placing them with Russian families and indoctrinating them in so-called re-education camps [rule of 3]. That is not just child abduction; it is cultural erasure [not just, but]. That is why the International Criminal Court has, rightly, issued arrest warrants for Vladimir Putin and his commissioner for children’s rights, Maria Lvova-Belova.

Let me turn to what we as Conservatives did in government in response. When Russia invaded Ukraine, the UK did not hesitate. We were among the first to send advanced weapons to Ukraine, including anti-tank missiles, long-range precision arms and air defence systems [rule of 3]. We trained tens of thousands of Ukrainian troops under Operation Interflex, co-ordinated international aid and introduced the largest, most severe package of sanctions in UK history [rule of 3], targeting around 2,000 Russian individuals and entities. We also sanctioned Maria Lvova-Belova over the forced transfer and adoption of Ukrainian children.

Under our watch, we did not stand with Ukraine just in principle; we stood with it in practice [not just, but]. We understood, and we understand, that helping Ukraine to defend itself was about not just charity—it was about national security [not just, but], and we treated it as such. We also understood, however, that Russia’s war crimes required a broader response. That is why we supported the gathering of evidence for war crimes prosecutions, championed media freedom and democratic resilience in Ukraine, and supported Ukrainian civil society, which is the lifeblood of any free nation [would a human naturally describe civil society as the ‘lifeblood’ in this way? Also seems off-topic in the war crime response context].

I was proud, in and out of government, to advocate for Ukraine, from sanctioning oligarchs and calling out disinformation to welcoming Ukrainian families into British homes through the Homes for Ukraine scheme [rule of 3], including some in my own constituency. What are the Government doing to build on that legacy? I am sure the Minister will set that out.

The moral imperative could not be clearer. Returning these children must be a top diplomatic priority, not just for Ukraine, but for the entire international community [not just, but]. If we do not act now, we normalise the weaponisation of children in conflict and we send the message that the forced erasure of national identity can go unpunished. What are the Government doing to press international bodies, including the UN and the OSCE, to intensify efforts to track and return these children?

What support is the UK providing to Ukrainian and international NGOs that are engaged in tracing, documenting and litigating these cases [rule of 3]? What diplomatic pressure is the Government applying to countries that are complicit in circumventing sanctions or turning a blind eye to Russia’s war crimes, including Belarus, which has been directly implicated? I welcome the commitment to £3 billion in annual military aid to Ukraine, but how much funding is earmarked for protecting civilians, documenting atrocities and countering the ideological indoctrination of abducted children [rule of 3]? Ukraine does not need just tanks; it needs truth and justice [not just, but].

I end with this: in every Ukrainian family torn apart by abduction, there is a mother waiting, a father grieving and a sibling left behind [rule of 3]. Each stolen child is not just a tragedy, but a test of whether the democratic world will match words with action [not just, but]. We on this side of the House say that we must. We led the way in government, and we will continue to hold the line in opposition. We owe it to Ukraine and the families, and we owe it to every principle that this place is meant to defend.

Clearly, the ‘rule of 3’ and the ‘not just, but’ formula are also used by humans; if they were not, they would not be used by ChatGPT so often. However, in my view, you would struggle to find any text written by a human that uses them nearly as much as in this speech. That is before even considering some of the other suspicious elements in the speech. In fact, I left out highlighting some of the melodramatic short statements (‘We need to call it out for what it is’ or ‘The moral imperative could not be clearer’) which are, in my view, usually strongly suggestive of AI, but may have another cause in this context: Anthony Powell noted that some officers altered their speech during the Second World War to take on a more Churchillian meter; it is entirely possible that Morton has done a similar thing, but with the much less inspirational figure of Boris Johnson. There are also some other incongruities and strange phrases that I have not flagged because they could just be put down to bad writing.

This is not a piece that is intended to single out Morton. If our supposition that this speech was substantially written by ChatGPT is indeed correct, our data shows that she is not alone. There are therefore plenty of other examples of suspicious speeches, and I will briefly quote short excerpts from two others with my comments. I did not search particularly far or wide to find these speeches. They were selected more or less at random, and there may be far worse cases that I’ve missed. I hope they also show how it can be difficult to find and quantify the amount of ChatGPT use: ‘tears are a natural result of such a devastating awareness’ — a phrase used in the next speech excerpt — sounds very weird, but there is no reason it would show up in any statistical analysis.

First, Shockat Adam, the newly-elected Independent MP for Leicester South, speaking in a debate about long-term medical conditions:

For example, macular degeneration is the leading cause of blindness in the UK. It does not just take away people’s central vision [not just, but]; it also affects their ability to read, recognise faces and drive [rule of three]. That means grandparents may never be able to see the faces of their grandchildren; tears are a natural result of such a devastating awareness [very strangely-worded statement]. There is also a condition called glaucoma—generally diagnosed later in life—known as a thief of sight, because it creeps up on someone silently, often unnoticed, until irreversible damage has been done. It steals more than vision; it robs [not just, but] people of confidence, safety and the ability to live independently [rule of three]. For many, the diagnosis comes too late, and with it comes a slow loss of identity.

Second, Mohammad Yasin, the Labour MP for Bedford since 2017, speaking in a debate about university funding. This speech is somewhat less suspicious than the previous two, but we can still flag a number of phrases even in this short passage:

In just the past month, universities in Dundee, Coventry and Bradford [rule of three, though this is more likely to just be a coincidence than some other cases flagged] have announced similar measures. Perhaps most shockingly, Kingston University has proposed the closure of its humanities department. The closure of a humanities department, in a country renowned for its literary and cultural heritage—Shakespeare’s birthplace, no less— [this detail is very strange, and gives the impression of ChatGPT usage — it is usually the kind of comment that people add about other countries, not their own] signals a troubling future for our higher education system. It is not merely a loss for humanities; it is a loss for the future of education in our nation [not just, but] and a blow to our global reputation as leaders in education. These subjects are disproportionately impacted by the cuts, and that reinforces the damaging notion that studying arts is the privilege of a select few—a hugely regressive step.

To repeat again: there is no definitive proof that any of these three speeches made use of AI; however, there is at least some reason for suspicion. By contrast, this speech by Keir Starmer in PMQs is a good point of comparison as a speech that has far fewer of these verbal tics that are closely associated with AI-generated text.

If I am correct in suspecting the widespread use of AI to generate Commons speeches, then it is profoundly depressing that some of our MPs (or at least the people working for them) appear to be so unimaginative, so illiterate, so empty, that they are willing to outsource what should be an MP’s greatest task and honour to a machine. I do not want a future where boring ex-public sector workers read out AI-generated statements about their hobby horses in a sterile, semi-circularly arranged ‘Parliament’ with enforced silence. The art of the parliamentary speech and the tradition of confrontational debate are worth promoting and protecting.

Appendices

Appendix A

Many of the terms reported to be favoured by AI are:

Words that have been heavily used in certain other contexts within Parliament, such as ‘seamless’ or ‘framework’ during Brexit negotiations, ‘landscape’ when talking about construction, or ‘realm’ in ‘defence of the realm’. Therefore some of these words have been left out, although a couple (landscape, ecosystem) are included for reference.

Words or phrases that are overused when ChatGPT is used in the majority of cases — academic work, reports, and emails — but not necessarily so if an MP is prompting it to ‘write me a speech to read in Parliament about [X]’. ‘Delve’ might be a case of this.

Simply not used frequently enough to be able to draw any inferences from the data.

Appendix B

Annual adjustment factors: 2007 (1.0236), 2008 (0.9819), 2009 (1.0988), 2010 (1.0299), 2011 (0.9772), 2012 (1.0675), 2013 (1.0130), 2014 (1.0548), 2015 (0.9999), 2016 (0.8190), 2017 (1.0207), 2018 (0.7943), 2019 (0.9556), 2020 (1.0791), 2021 (0.9729), 2022 (0.9816), 2023 (1.1613), 2024 (1.2006), 2025 (1.2872).

Appendix C

Of the four words, ‘delve’, ‘intricate’, and ‘elevate’ are used at relatively low frequencies, which makes the data noisier and it harder for a pattern to be visible. All three of those do actually have a positive Z-score in 2024 and 2025 — except ‘delve’ in 2025, which is ≈0 — i.e., they are being used more frequently than average; it’s just not at a statistically significant level or part of a meaningful pattern.

This article was written Apple Tokamak, a Pimlico Journal contributor. Have a pitch? Send it to pimlicojournal@substack.com.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing. If you are already subscribed, why not upgrade to a paid subscription?

A very interesting article. I help run a poetry group on Facebook with the remit to take down AI generated poems. With chatGPT's more advanced models it can generate free verse which is more difficult to spot. Rhyming poems stand out a mile. But I'm sure I've seen examples of rule of 3 and not just ... but in AI free verse poems.

If, and only if, I suspect a poem is AI, I run it through AI detector platforms like gptZero, Quillbot, and Copyleaks. I ran the Wendy Morton speech (from the text in Hansard) through each of these and they scored 0% - in other words the detectors were highly confident it was human.

I wonder if there are more recent detection tools that can spot "rule of three" or "not just - but" instances.

I think this mostly demonstrates that debate in a deliberative body has long since become obsolete and useless, due to rise of easy long-distance communication and information access/retrieval.