Five myths about immigration and economic growth

What John Burn-Murdoch still isn't telling you about immigration

Every day in every way, we are told that the constant arrival of immigrants is essential to Britain’s economic health. Only the other day Tom Forth was on X declaring that, although GDP per capita was probably falling — given GDP is stagnant while immigration is hitting record levels — this was ackshually a good thing because the alternative ‘is a deep recession, higher public debt, and deeper cuts to public services and/or tax rises’. Be grateful!

It’s not true. The good editors of Pimlico Journal have asked me to set the record straight, having once again sat through innumerable John Burn-Murdoch threads which left them none the wiser. And so, here we are, the much-anticipated immigration and economic growth mythbuster.

First, a word about welfare functions. The gains from more open immigration are potentially very large, but most of them go to the migrant. If an unskilled Somali moves to Britain and works in a sweatshop for half of the minimum wage, they will be fabulously well-off compared to their likely living standards back at home. In fact, such is the gulf in living standards between Britain and Somalia that this is the case even if the Somali has skills.

This article doesn’t give a damn about our skilled Somali chum, who is getting those gains by competing with British workers in our labour market and by using infrastructure that British people have accumulated over generations (including social housing). Like the august Financial Times commentator Martin Wolf, this article thinks that the economic impact of immigration should be weighed in terms of its benefits to the British people, and only the British people. As Martin said:

…I would argue that this weight [i.e., the welfare of future immigrants] should be zero. Under a zero weight on the welfare of future immigrants (surely the position of most British citizens), the policy question becomes not what is the impact on GDP per head, or productivity per worker, but the impact of immigrants (of different kinds) on GDP per head (and its distribution) for those already in the UK.

Even Jonathan Portes, noted immigration fanatic, agreed that this was a reasonable position, so let’s call it the official consensus of all sensible people.

Myth #1: The only thing supporting economic growth right now is immigration

Immigration is the lifeblood of the economy, and without it we’d have no economic growth.

This myth is everywhere. Britain’s economic policy wonks have long since given up on most other routes to growth besides stoking the labour market supply (‘skills’ is another, related one), such that they seem relatively unbothered that building houses or factories can often be illegal, or that electricity is only available at ever-increasing prices (and is often becoming increasingly unreliable at any price).

Immigrants: well, if they wanted them, they got them. (The public never wanted them.) By 2023, 19.4 percent of people employed in Britain’s labour market were born abroad, up from 7.3 percent in 19971 — that’s 4.5 million more workers, all from overseas. If immigration is the lifeblood of the economy, then Britain’s economy must be booming, right?

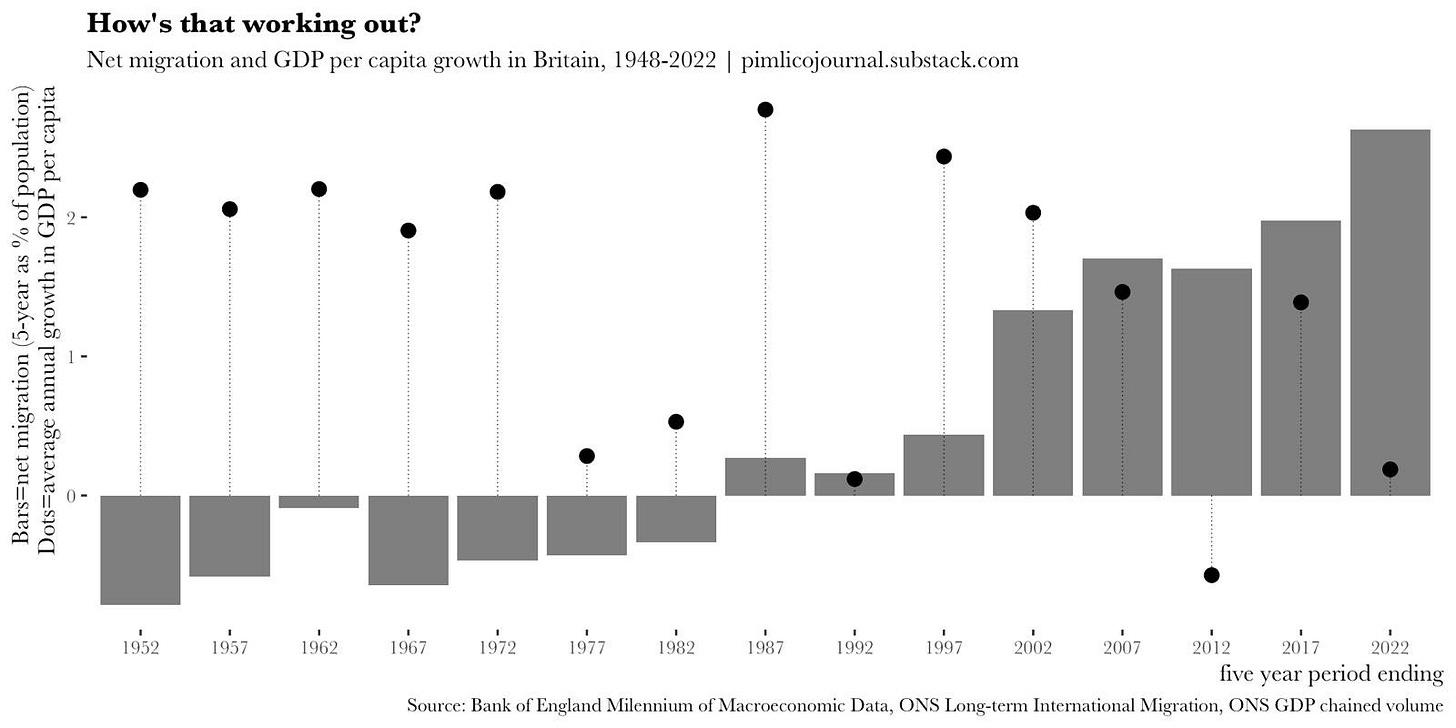

Right? Never had it so good? Not so much. The first few years of that period seemed to go pretty well, helped by a global boom in financial services; the last fifteen years of it have been a constant story of the British economy falling further into near-stagnation. While employment has boomed — those migrant workers must go somewhere, after all — earnings growth has been stifled and many costs are increasing. The chart below shows the history of immigration and economic growth since 1948, the year when mass immigration became a part of modern British life. Net migration first reached genuinely transformative levels in 1997, and in the same period, growth in GDP per capita has seen sharp and sustained decline.

As the economy decays more and more, we bring in even more immigrants in the hope that this might turn something up, yet it is plain for all that choose to see that this experiment has failed. But why has it failed? There are many explanations as to why immigration is supposedly essential to economic growth, so let’s take them by turn.

1.1 We need immigration to fill all the jobs!

‘We have over 1 million job vacancies! We need immigrants to fill them!’ and ‘We need immigrants to do the jobs British people just won’t do!’ — you’ve heard it all by now.

It shouldn’t be necessary to say this, but the economy is not a vampiric god which needs constant deliveries of fresh human meat to shower its blessings upon us. Surprising numbers of seemingly intelligent people seem to believe otherwise, something that has long been diagnosed as the lump of labour fallacy. Immigration fans love the lump of labour fallacy half the time, as it shows that just because the demand for labour responds to the demand for goods, immigrant workers don’t (in aggregate, at least) ‘take jobs’ from natives, as their supply induces new demands.

But by the same logic, the absence of immigrant workers does not mean jobs would go undone — employers would instead adapt their plans, choosing to raise pay to attract native workers, or to invest in plant and machinery in place of workers. Employers don’t simply leave jobs unfilled permanently, even though there are no workers willing to take them; they respond, deciding between pay rises and increased investment, depending on the options available to them.2

1.2 We need immigration to meet skills shortages!

A more elaborate version of the same argument is that we need immigrant workers because of more localised, specific shortages, especially related to ‘skills’. The economy may not be a vampiric god, but there may plausibly be ‘pinch points’ where scarce skills make for constraints to growth. Doctors, engineers, and scientists are all mentioned, although it should be said that the government’s Shortage Occupation List which embraces this concept covers a much wider range of jobs, such as health bureaucrats and arts officers, which don’t seem quite as hard to adapt to as neurosurgery.

This is a more promising argument, although when in 1959 Kenneth J. Arrow — Nobel prizewinner, mathematician, and father of modern economics — reviewed the argument in the case of engineers and scientists, he and his coauthor William Capron concluded that ‘dynamic shortage’ was ultimately just the process of market adjustment:

While the relative rigidity of supply in the short run is unpleasant (from the buyers’ standpoint), and the price rise required to restore the market to equilibrium may seem to be very great, it is only by permitting the market to react to the rising demand that, in our view, it can allocate engineer-scientists in the short run and call forth the desired increase in supply in the longer run.

Arrow and Capron derided the claim of worker ‘shortage’ as no more than ‘a misunderstanding of economic theory… [and] an exaggeration of the empirical evidence’. They suggested that ‘rather than admit that they could not pay the higher wages necessary to keep help, many individuals found it more felicitous to speak of a “shortage”’. In a large economy — and Britain has 30 million people at work, after all — there will always be stresses in the competition for scarce resources, including for skilled workers. This is not a problem to be avoided; it is the inevitable consequence of a dynamic economy.

Arrow and Capron were writing a long time ago.3 Might there now be new evidence on the pressing need to meet these supposed ‘skills’ shortages? In 2022, 10 percent of employers reported having at least one job that they couldn’t fill because of a skills shortage, up from 6 percent in 2017, and 3 percent in 2011. 36 percent of employers’ vacancies were characterised by a ‘skills shortage’, up from 22 percent in 2017, and 16 percent in 2011. Superficially then, skills shortages are galloping, but in the same eleven years from 2011 to 2022, Britain added 3.6 million immigrants, net, to its population, yet employers nonetheless claim that ‘skills shortages’ have gotten worse rather than better. If the economy was really being transformed in a frenzy of investment and dynamism, this could perhaps be plausible, but the dreary reality is that it’s no more than a weak excuse for employers looking to get cheap labour.

1.3 We need immigration to avoid inflationary shortages!

The final flavour of ‘shortage’ arguments is that although employers can solve their shortages by paying more to attract the workers they need, this is actually… bad. The story goes that if employers are compelled by a tight labour market to give their workers a pay rise, this will feed through into their own prices, thus driving inflation.

Disappointingly, many economists (especially in the City) seem to love this argument, as it allows them to feel Very Serious. But it’s entirely spurious, as can be detected by the fact that the very same economists are more than happy to accept a pay rise any time it’s offered.

Inflation is driven primarily by an excess of money supply above demand. Commodity price shocks can make countering inflation painful, and so rising costs can in practice drive inflation up. But commodity prices are set in world markets, while most wages are set in national ones, denominated in pounds, and so represent no threat to the Bank of England’s power to control inflation.

The uncomfortable truth for the immigration advocates making this argument is that, leaving aside the spurious inflation angle, it is a proposal that immigration delivers its benefits by expanding the labour supply for a given level of wages. That is, it is seeking to use competition from new foreign workers to avoid having to give native workers a pay rise. According to our Martin Wolf welfare function — which remember, is strictly for natives — this seems like an immediate fail, as there are very few circumstances where the returns for British employers will offset the lost pay rises for British employees.

1.4 We need immigration to fuel our thriving service sector!

At the core of this argument is that migrants’ skills will differ in substantial ways, allowing for a new division of labour which can actually benefit natives. This just-so story has it that we can leave the low-end jobs like food packaging or Deliveroo to the immigrants, while British workers can focus on better jobs, with their productivity improved through specialisation.

This is a reasonable argument. Britain has been able to expand its low-end service and production economies through migrant labour, and British workers have become more specialised in other roles over the past quarter century. The problem is that the benefits of this ‘task specialisation’ are modest to the point of trivial, as Peri and Sparber found in one of their papers studying the phenomenon in the US (a 2-3 percent improvement in relative native-immigrant wages as a result of a 60-90 percent increase in the immigrant labour supply; absolute wages were still a little bit lower when this was netted off). If this is the only way immigration contributes to economic growth, it’s trivial.

1.5 We need immigration to avoid being like Japan!

This 1990s talking point hangs around as if Britain hasn’t joined Japan in a period of relative economic stagnation over the past fifteen years. The story goes that Japan, an allegedly closed and backward economy, has seen its economy in sharp decline owing to its relative wariness of gaijin. In 2021, Japan’s foreign population stood at just 2.3 percent.

Between 2002 and 2022, Britain has seen its GDP per capita (constant PPP, via World Bank) grow by an annual average of 0.8 percent, roaring ahead of Japan, which has grown by an annual average of… 0.7 percent.

1.6 We need immigration to avoid having to invest in machines!

Ok, nobody actually makes this argument. But I’ve said that they do purely to shoe-horn in the other side of immigration and economic growth: namely, that employers like immigration because it gives them an open-ended labour supply which means they don’t have to invest in capital equipment and new technology.

That British employers don’t invest is widely acknowledged as one of the key failings behind our productivity stagnation (here, here, here). Such is the low level of investment, in the context of rising employment, that the ONS’ analysis is that the market sector of the British economy has seen ‘capital shallowing’ – that is, a falling value of assets and machinery per worker – for almost all of the 2010s. One of the interesting features of the economic policy debate is that the wonks are all very concerned about the fact of Britain’s shift to an ‘even more… labour-intensive, lower-capital model for growth’, but they remain conspicuously incurious as to why this might be so.

Critical to the explanation4 is that mass immigration has made labour cheap and abundant, meaning that employers pursue growth through scale and not through investment. Why grow by costly and risky investment when you can sweat your assets with a few more cheap bodies?

This outcome is further incentivised by the same ‘skill complementarity’ we’ve already discussed: an abundant supply of cheap workers mean we can have more people packing food rather than getting machines doing it. Those sectors have often been at the forefront of capital shallowing.

To see the mechanism in reverse, we can use a historic case study from open borders advocate Michael Clemens. In a study a few years ago, Clemens and his coauthors looked at a specific postwar case where Mexcian bracero immigrant labour was cut off from the US agricultural sector. Their conclusion was that this had failed to help US workers improve their conditions, but what they really showed was that in that setting they had triggered a wave of productivity-enhancing investment:

…bracero exclusion failed to substantially raise wages or employment for domestic workers in the sector. Employers appear to have instead adjusted to foreign-worker exclusion by changing production techniques where that was possible, and changing production levels where it was not.

In an environment where technology is chiefly labour-saving — which we see whether it is robotics or AI — then labour being scarce will encourage innovation and capital investment, and the consensus is that investment will feed productivity. If, on the other hand, we choose to keep labour permanently and increasingly abundant, then businesses can achieve gains without financing significant investments, but productivity flatlines and British workers gain little or nothing.

Myth #2: We need immigration to balance the books

There’s a very real fear at the core of this one, namely that as Britain’s population ages, we need fresh blood to keep our population pyramid in good shape so that the burdens of pensions and social care don’t become too great on the working-age population. But on top of that, a more wide-ranging argument is often mounted: specifically, that immigrants are net contributors, philanthropically bringing their taxes to pay for the public services which the natives need (while, apparently, not adding any further demands).

2.1 We need immigration to replace our ageing population!

Like all advanced economies, Britain is ageing. Sub-replacement fertility rates and advancing healthcare (and life expectancy) together mean a retired population growing much faster than the working-age population. Therefore, so the argument goes, we need immigration to bring in young bodies to balance out our increasingly decrepit British selves. You will find a variation of this argument even being made by some conservatives — Paul Morland and Philip Pilkington argue that unless Britain tackles its declining fertility, the choice is between mass immigration and economic stagnation, much like in Japan (but as we have already seen, Japan is hardly much more stagnant than Britain).

The main problem with this argument is pretty obvious: immigrants get old too. In 2000, the United Nations Population Division investigated the potential of ‘replacement migration’ as a solution to population decline and ageing. The fun finding was that in order to maintain a constant dependency ratio between retired and working age people, the Republic of Korea would have to have net immigration of 5.1 billion people over the next five decades; most of the world’s population would have to move there. Even for Britain, the same policy goal would require 60 million net migrants, or 1.1 million each and every year. So if you think immigration has been high in the twenty-three years since the report, consider that it’s been at a mere third of the level that they estimated would be required.

In cautious language, the UNPD pointed out the obvious: such levels of immigration would be unprecedented and unsustainable, replacing not just ageing workers but whole societies. The report notes that

…by 2050, these larger migration flows would result in populations where the proportion of post-1995 migrants and their descendants would range between 59 percent and 99 percent. Such high levels of migration have not been observed in the past for any of these countries or regions.

A more reasonable argument here is that immigration can help the adjustment to an ageing society, using a number of younger workers to slow the process down. But if population adjustment is an objective of immigration policy, policymakers are failing spectacularly. To be successful, the British state would have to enforce robust selection to ensure only younger migrants arrive, and on visas covering only their working life. In the 2021 Census, the ONS found 73,600 people aged 65 or over who had arrived in the previous 7 years, with another 241,700 people aged 50 to 64. While in theory elderly immigrants haven’t accumulated state pension rights, the state still has Pension Credit to provide a means-tested alternative.

2.2 We need immigration because of the contribution immigrants make to the public finances!

Leaving aside the long-term question of ageing, a broader point immigration advocates make is that immigrants bring vital new taxpayers which help our increasingly dysfunctional state finance itself. They point to several studies which hint at immigrants having significantly better net fiscal contributions than natives, i.e., that immigrants pay more in taxes than they consume in services.

This line of argument first really took hold with Dustmann and Frattini’s Economic Journal article ‘The fiscal effects of immigration’. Looking at data across 1995 to 2011, they found that EEA migrants (often higher-skilled and younger) had made a significant positive fiscal contribution, while non-EEA migrants (who had often arrived decades before) were a large fiscal drain. Yet while media commentary excitedly pushed the positive finding, they downplayed or ignored the negative.

Fiscal analyses mainly come out with a pretty neutral, unexciting outcome. But some of the assumptions which get baked in are important, because the outcome starts to move fast once those assumptions change. Some good examples are to be found in an OECD study in 2021. For example, immigrant arrivals are typically of working age, and therefore are more likely to be working and less likely to be consuming many public services. As such, in the OECD’s analysis of Britain, the migrant:native fiscal ratio moves from 1.23 (i.e., 23 percent higher fiscal contribution) to 0.97 (3 percent lower) simply by making their age profile the same.

Another assumption the OECD uses is that immigrants’ children born in Britain aren’t part of the fiscal cost of immigration. But over time, these get to be significant numbers — changing this assumption (as the OECD do in Table 4.2) swings the estimated fiscal contribution from 0.23% GDP to -0.20% GDP. Taking together the potential for the age profile to degenerate and the full cost of children, even in aggregate there’s the potential for the neutral outcome to tend negative.

The truth is that aggregate analysis is driven in the details. An all-too-common mistake in policy analysis is to take the average outcome as a guide to the marginal outcome. Hence, in the 2000s, with the wave of EU freedom of movement and the Eurozone crisis, a significant cohort of culturally similar, often highly educated workers arrived from Eastern and Southern Europe, with their average fiscal contribution being broadly neutral. But what if — as visa statistics show — we are now rapidly accelerating non-European migration, often from third world countries, and often with high numbers of dependants? And what if — as the boats on the Channel show — we are also knowingly receiving increasing numbers of refugees from highly dysfunctional countries? This chart is important in this regard, and despite its title, not at all complicated:

Denmark, like many Nordic countries, maintains a robust population register linked to a range of other data, and so can model rich data on the paths of natives and foreigners through Danish society. The finding here is dramatic — MENAPT (Middle East, North Africa, Pakistan, Turkey) immigrants are at no point in their lives net contributors to the Danish public finances.

This shouldn’t be surprising. The underdiscussed aspect of Dustmann and Frattini’s paper was that post-war Commonwealth migrants made a sizeable net negative fiscal contribution; the Danish data simply gives a much more detailed picture of similar trends. As background, 54 percent of British households (natives as well as immigrants) receive more in benefits and public services than they pay in taxes. The median household in Britain is not a net fiscal contributor; if immigrant households are anywhere around or below that median household, they probably won’t be either.

There is an assumption that many immigrants are here in Britain performing high-skilled jobs, but that’s not an accurate portrayal. Overall, those born abroad are about as likely as natives to be found in a management or professional role, but the rest of the workforce looks quite different. 32 percent of working age employees born in Britain are in low-skilled jobs, compared with 41 percent of those born abroad.5

Given what we know about fiscal contributions across Britain, the very high proportion of immigrants in low-skilled jobs makes its own point. In keeping with the Danish analysis, where immigrants come from makes an enormous difference. In this chart the dotted rectangles show the native-born distribution, and we see that while workers from North America, Oceania, and the EU15 are biased to high-skill jobs, immigrants of all other origins are over-represented in low-skilled jobs.

The upshot of all this is that while you can conceive of a fiscally positive immigration policy, harvesting highly-skilled workers chiefly from advanced economies like the US and the richer parts of the EU… Britain definitely isn’t pursuing it. And we never have pursued it. After all, if Britain’s recent immigration cohorts were blessing us with so much fiscal gold, how is it that the state lurches from fiscal crisis to fiscal crisis every three or four years? How is it that the budget has barely ever been within sight of balance for a decade and a half now?

Myth #3: Immigration is win-win, nobody loses

The great thing about immigration is that it’s immaculate in its impact, and that immigrants’ gains — remember our Somali chum? — are achieved with no loss at all to the natives. That in itself is a questionable claim, but there’s a further one: that immigrants’ presence means a marked improvement in standards of living, with our culture enriched — will no one, please, think of the restaurants?! — as well as cheaper services and staffing up vital public services. There’s no downside at all, only upside. But is it really true?

3.1 Immigration doesn’t hurt people’s wages!

This is highly contested terrain, but it’s fair to say that establishing the expected impact of expanded immigration labour supply on native wages has not been without controversy — a problem widely recognised. There are good reasons why this might be the case, and we have enough indicators telling us that something is happening.

In a simple economic model, immigration should certainly have a short-term effect on wages, but its long-run effect can continue to be negative under certain conditions, for example:

If the impact on the consumer base (demand) is smaller than its impact on the size of the workforce (supply) — which, given that immigrants overall have a below-average skill profile and send significant remittances back to their home countries, looks likely to be the case.

If capital supply isn’t elastic, then the greater abundance of labour will not be followed by sufficient investment to avoid ‘capital shallowing’ (explained above), meaning that wages will remain persistently lower; as we have already discussed, failing capital investment is widely acknowledged as a feature of the British economy during the period of massive, accelerating immigration.

Lots of studies suggest immigration wage effects which are tiny, and sometimes even positive — why is that? Part of the problem is finding the signal in the noise: immigrants arrive and go to where the job opportunities are, i.e., where the demand for their work is high. London’s economic growth has pulled in many immigrants, whereas struggling regions have pulled in comparatively fewer. But if London was growing anyway, would wages have risen even faster without new arrivals?

There is also the question of ‘skill complementarity’: if immigrants’ different skills allow natives to specialise in new, higher-paid jobs, then they can gain in the process. But that’s only of use to those who can make the switch. While some native workers are complemented by immigrants, those that (for whatever reason) can’t find more high-skill jobs face increased competition. Discussing the skill complementarity idea, the US National Association of Scientists pointed out that ‘native workers who are substitutes for immigrants, however, will experience negative wage effects’. Analysis of the immigration wage effect on native workers suggests this is true, with some gaining and some losing, although the directly attributable effects are very small.

Is that the whole story? The path of pay and productivity across this period suggests something has changed, with real wages essentially stagnant since the mid-2000s. In aggregate, these effects of lowering demand and shallowing out capital affect all workers, and it’s hard to pin down the direct effect of immigration, except to look at the emergent picture of failing investment and stumbling productivity growth.

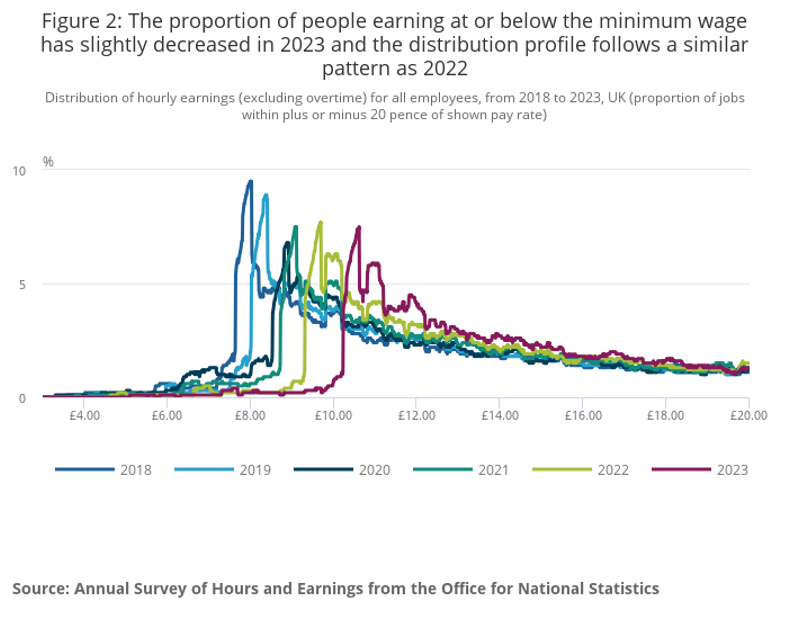

There are a few other moving parts to this story of the missing link between immigration and wages. First, although the low end of the labour market has been much more exposed to competition from immigrant labour, it should be remembered that pay at the low end has simultaneously been increasing by statute, through the National Minimum Wage and the National Living Wage. Data from the ONS over just the last six years show how minimum wages now dominate the bottom of the labour market:

That isn’t to say that market pressures from increasing immigrant competition aren’t there, it’s just that they manifest themselves in different ways. There is plenty of evidence that while employers at the low end of the labour market can’t easily cut workers’ wages, even when facing such a buyer’s market, they still have other ways of making workers worse off. Workers at the bottom end of the labour market have seen a sharp decline in job satisfaction since the 1990s, report significantly higher stress levels, and substantially reduced autonomy.

The sheer size of the existing immigrant workforce in Britain, especially at the low end of the labour market, has its own effect on all these questions. For example, many studies of wage effects look strictly at the effect on native wages, but for some years now it has been earlier cohorts of immigrants who are most exposed to wage competition. The negative impact on previous cohorts of immigrants’ wages has long been identified, and under our Martin Wolf welfare function this represents a direct fail.

There’s also a darker side to the immigrant labour market, which is the expansion of the grey economy. There are by now abundant stories of sweatshop employment across farms, car washes, nail bars, clothing factories and more. Often paying well below minimum wage, engaging in borderline slavery, and conniving in benefit fraud, this sector of the labour market showed few signs of existence before the massive expansion of immigration.

What if you’re not low-skilled, and not an immigrant? Is there no downside for your rewards from work? A useful perspective can be found by a study by Christian Dustmann and his coauthors, making use of a natural experiment of opening the Czech-German border fourteen months after the fall of the Berlin Wall, allowing Czechs to take advantage of the much more prosperous German labour market.

Unskilled natives faced the greatest consequence, but the data showed that the effects differed by age — younger natives (aged 30 and under) saw a wage decline, while older natives (50 and older) saw a decline in employment. The implication is that older workers hold out against wage cuts, while young people with a career ahead of them accept them.

What’s interesting is that this seems to fit with the generational differences in wage growth in Britain over the last few decades. Although causation is predictably complex and difficult to establish, poor wage growth for younger generations has coincided with massive increases in immigration. This chart from the Resolution Foundation helpfully shows that across the lifecycle, wage growth seems to have stopped in its tracks for the most recent cohorts making their way through the labour market, with the median 30-something graduate paid less in real terms in 2022 than in the late 1990s. At the same time, one-in-five 50-somethings in employment are self-employed, and data from HMRC shows that self-employment has a long tail of low income:

To summarise: it’s difficult to draw a direct line from the arrival of immigrants into the British labour market and the bleak outlook for pay and conditions for workers in Britain, but the arrows all point in one direction. Pay has been hit over the past fifteen years, particularly for younger workers and previous cohorts of immigrants. There have been attempts to hold low-end pay up by statutory means, but there is nonetheless a backdrop of worsening conditions extending to sweatshops. The failure of employers to respond to increased labour supply with a wave of investment — just the opposite, in fact — makes it no surprise that this has become a persistent pattern: ever-more immigration dragging capital levels and labour productivity down, and pay and conditions along with it.

3.2 Immigration makes the cost of living fall, we’re all better off!

On the other hand, maybe immigration really has made us all better off — just not through our wages. Today’s younger generations may face the despair of worsening pay and conditions but, as Liz Truss suggested, they maybe can make up for it by being #Uber-riding, #Airbnb-ing, #Deliveroo-eating #freedomfighters?

There is a serious proposition here: that mass immigration allows us to ensure an abundant supply of low-wage service workers, whose minimal rates of pay keep the costs of services low. We can even dress it up and say that immigration has been the way that the British economy has sought to escape Baumol’s cost disease of services, where rising productivity in one sector causes costs to rise in labour-intensive service industries in order to retain the necessary workforce. Consequently, although immigration might well have hit wages, it’s got benefits in terms of reduced costs for certain services — think of how many people now have a cleaner, or quality childcare, but would have been unable to afford it twenty or thirty years ago.

The problem with this argument is that it looks at one side of the cost of living, but not the other. Immigration may well have helped expand the supply of labour-intensive services, but it’s overwhelmed the supply of capital-intensive services. The British experiment with mass immigration since 1997 has proceeded strictly on a Buy Now, Pay Later basis. Housebuilding has not adjusted: we continue to build new homes at the same rate we did before we started adding the population of a provincial city every year for twenty years. Britain hasn’t built a new reservoir since 1991, a nuclear power station since 1995, has been arguing for decades about adding one (1) runway to the second busiest airport in the world, and has been backtracking furiously on building its second major high-speed railway line.

The impact is plain to see for anybody living in Britain: soaring housing costs, creaking and congested transport, water and electricity increasingly unreliable. You might well enjoy access to a cheeky Deliveroo and the benefits of a house cleaned without any effort, but it’s small consolation when the rent goes up year after year — again, hitting the youngest hardest, as older generations are much more likely to own their own homes — your train gets cancelled, and the electricity starts to brown out more and more. The same dynamic applies in public services: using abundant immigrant labour to expand — especially without paying to train a sufficient native workforce in the case of the NHS — while schools and hospitals have difficulty coping with ever-rising demand.

This comes back to wage adjustment to an immigration shock depending on elastic capital supply: just as with business investment, these forms of capital haven’t adjusted to the demands of a rapidly increased population, and so although you don’t always pay a higher monetary cost, your experience of using them deteriorates more every year.

You can blame austerity, but the free-spending Blair and Brown governments started this process of expanding immigration with no plan as to how new arrivals are to be housed, transported, and warmed, except to compete for resources with the native population. You can also lament that ‘if only governments had invested, we wouldn’t be in this mess’, but investment isn’t free. Every extra house built, or infrastructure improvement delivered, requires funds and workers that cannot be used to deliver for consumers or investors elsewhere in the economy. As we have seen, the economic benefits of immigration are hard to find: if we had said we were devoting the resources necessary to provide for the millions of people added through immigration since 1997, the decision would have been extremely unpopular. Now, after it’s happened, the bill has anyway come due.

3.3 Immigrants are workers, they’re not drawing on the system!

Aside from depressing wages and congesting housing and infrastructure, immigrants are here because they’re the strivers who’ve chosen to cross the world to be in Britain. They’re here to work, not to access benefits, unlike many British people!

Is that fully true? Certainly at the point of first arrival, immigrants often do have some limitations on their entitlement to access certain benefits and services. But if the test — our Martin Wolf welfare function again — is whether immigration benefits British people, then we should set a high bar on immigrants’ claims to public support. In practice, the bar seems very low.

Start with taxes and benefits at the most elementary level. In the latest data (2018/19), 4.9 million foreign nationals were paying National Insurance in Britain (NI kicks in before income tax). Between them, they paid £49bn in income tax and NI, but they also received £7bn in child benefits and tax credits. These are the first line of the welfare system, administered through HMRC rather than the Department for Work and Pensions. Dividing each country’s taxes paid and benefits received by the number of National Insurance payers, an interesting pattern emerges: perhaps unsurprisingly, immigrants from the US pay large amounts of tax and draw few benefits, with Canada, France, and Australia also among those in a similar place.

But above the diagonal line here, Somali, Afghan, Syrian, and Bangladeshi nationals who work enough to pay National Insurance (not including the economically inactive) receive more in tax credits and child benefits than they pay. These may seem like outliers, but consider that only just to the right of the diagonal line is Pakistan: for the average Pakistani national working and paying NI in Britain (156,000 of them in total for 2018/19), £6,147 taxes were paid, but £5,205 in tax credits and child benefits received.

Remember: those benefits are just the start; although why foreign nationals are entitled to redistributive benefits like tax credits in the first place, one might wonder. For wider working age benefits, we get data from DWP. These data come from 2020, but the COVID pandemic inflated all benefit claims, so we shall focus on the more normal 2019 numbers. In that year, 1 million foreign nationals — 380,000 EU and 610,000 non-EU — claimed some kind of working-age benefit. The geographic pattern follows the trend of all the data here: 200,000 from South Asia, 150,000 from Sub-Saharan Africa, 110,000 from the Middle East and Central Asia.

More detailed data on the benefits claimed is only available for the more volatile 2020, but it is still striking. In that year, 18 percent of Universal Credit claims for being out of work were for non-British nationals, rising to 26 percent of those claiming Universal Credit while working. In many cases, though, non-work is an issue: excluding students and the retired, economic inactivity among men runs at 23 percent for those born in Somalia, 20 percent for those born in Turkey, 19 percent for those born in Bangladesh, 19 percent for those born in Jamaica, and 16 percent for those born in Pakistan, as compared to 12 percent for English men. There are many countries of origin with lower levels of inactivity — Nigeria is 10 percent and the Philippines 7 percent, to give two examples — but that makes the point: immigrants are supposed to be here to make a life for themselves, that’s why the argument of them striving and contributing is so often made, but sadly it too often isn’t true.

That brings us to housing. Here in the pages of Pimlico Journal, last month saw groundbreaking analysis by JUICE examining just how much of social housing — especially in Central London, some of the most valuable real estate in Europe — is now reserved for immigrants rather than native Britons. Fully 48 percent of London’s social housing stock is let to households headed by someone born abroad, with 31 percent having arrived only since 1991. 74 percent of all Somali-headed households in London live in social housing, compared to 24 percent for households headed by someone born in Britain.

Large numbers of socially rented household heads are of prime working age and yet are economically inactive, despite the claims that their accommodation in these expensive homes are somehow necessary for the economy. Social housing is typically offered at rents 50 percent below the local market rate, so this allocation of social housing to immigrants represents a massive subsidy that is in effect hidden from all balance sheets. And despite immigrants’ presence within social housing, they also feature highly in claims for Housing Benefit — a benefit focused on those not in social housing — with 19 percent of Housing Benefit claimants in 2020 being non-British nationals, rising to 40 percent in cases not connected with sickness and disability. In London in 2020, 206,000 non-British claimants were receiving help through Housing Benefit in some form, compared with 215,000 British claimants.

None of this is to say that there aren’t many hard-working, high-taxpaying immigrants in Britain: there are many, and many will be as frustrated by these facts as you are. In aggregate though, there are far too many immigrants who are in Britain and receiving large amounts of state help without contributing much in return.

Myth #4: Immigration is the rocket fuel for long-term productivity growth

Ok, so aside from the fact that after twenty-five years of mass immigration, Britain has failing economic growth, a state which lurches from fiscal crisis to fiscal crisis, and degenerating living standards, especially for the young: maybe it’s just one more heave, comrade? Perhaps the strategy is right — immigrants really will power Britain’s future prosperity — even if the delivery so far has been faulty. Or perhaps it’s just the birth pangs of a new economy, which will be so much better.

4.1 Immigrants are magical and they will enchant Britain’s economic future!

This line of thinking leads some immigration advocates to seek out ways of presenting immigrants which leave credibility far behind. Large numbers of military-age men from the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa crossing the Channel in inflatable boats? According to Jeremy Corbyn, ‘the asylum seekers of today are our doctors, carers, teachers, neighbours and friends of tomorrow’.

That’s the sillier end of the spectrum, but many other cases are not so far behind. The Entrepreneurs Network, a London-based think-tank which seems to specialise in shilling for visa liberalisation, recently published a new edition of its Job Creators research, which aims to show how critical immigrants are to supporting a vibrant start-up sector in Britain. Their headline finding is that 39 percent of the fastest-growing companies in Britain have a foreign-born founder, despite the foreign-born making up only 14.5 percent of the British population.

This is statistical manipulation: they count the share of one-hundred companies which have at least one foreign-born founder, even if that company has another three founders are British. This ‘one drop rule’ approach is in no way comparable with the share of the population, and the proper statistical comparison is the share of all founders who are foreign-born. A few weeks ago, I re-estimated their 2019 version of the research, which helpfully published the list of companies in question. Their headline statistic, more honestly applied, fell from 49 percent (their claim) to 20 percent (my estimation). And in the most relevant 25-49 year-old age group — not many pensioners (or children) from any country are founding start-ups — that’s below the foreign-born population share.

Numbers aside, TEN’s claim is relentlessly silly: their own research shows that the small group of foreign-born founders aren’t spread relatively evenly across the world, thus justifying a general visa liberalisation. They are primarily North American, European, Australian, et cetera. In similar fashion, every time it’s Nobel Prize season you will be sure to find stories about how many are immigrants — but a quick look at the country of birth for Nobel Prize winners tells a much simpler story: the overwhelming majority are from advanced economies, including Britain — British-born people have received more than all of Africa and Asia put together.

4.2 Immigrants bless us with their talents!

The more sober version of this story is that immigrants are coming with great new skills, which will expand our capabilities over time and allow us to achieve great things one day, some time in the future.

As we have already seen, the claim that immigrants are all coming to Britain to take high-skilled jobs is simply not borne out by the facts, with an over-representation of immigrants in low-skilled jobs. But perhaps the underlying skill levels are not reflected in current employment. There is good data to suggest that immigrants are more likely to have a degree than natives. Perhaps this is an indication of greater things once Britain uses their talents more productively?

As is so often the case with ideas about the economic contribution of immigration, it just doesn’t hold up. Richard Blundell and his coauthors looked at how immigrant graduates fare, and concluded that the superficial claim of higher education levels for immigrants isn’t borne out by their labour market performance. In research published only this past October for the Migration Advisory Committee, evidence from detailed earnings data shows that EU Accession state workers saw substantial ‘downgrading’ upon their entry into the British labour market, and also that this persisted, with them remaining ‘toward the bottom of the wage distribution [even] as their time in the UK increases… given the size of the initial downgrading wage penalty, these workers are on average unlikely to reach the wages of similarly qualified natives’.

A better approach to evaluating the claims that immigrants bringing superior talent depends less on qualifications, and more on the direct testing of cognitive skills. In a 2015 paper, John Jerrim used OECD testing data from 2011 to compare the mix of people who had emigrated from Britain with those that had arrived through immigration. His first finding is that high-skill immigrants have ended up offsetting the loss of high-skill workers through emigration, but, as his chart shows below

…the proportion of GB residents who are migrants increases as one moves down the skill groups… immigrants account for one in four adults living in GB with low-level numeracy skills. Consequently, immigration into GB has clearly had its biggest impact upon the bottom of the numeracy skill distribution. It has, in other words, led to a significant increase in the supply of low-skilled workers… It is interesting to observe that immigration from the South Asian and African regions adds six times more low-skilled individuals to the UK labour force than high-skilled individuals… Overall, net migration has therefore added 1.7 million low-skilled individuals to the GB population (compared to essentially no addition to the high-skilled population).6

The potential argument for immigrants bringing cognitive skills as a precursor to improved long-run economic growth certainly has solid foundations. Garett Jones in his book Hive Mind focuses on the critical importance of cognitive skills in explaining different levels of economic performance. But the harsh reality is that mass immigration in Britain as it has been and is increasingly practiced is not adding to our average level of ‘cognitive skills’, and it is condescending to British people to suggest that the average immigrant, let alone the marginal immigrant, is dragging up the nation’s human capital potential.

Myth #5: The link between immigration and economic growth doesn’t matter

One last myth, which is one we hear not from immigration advocates, but from critics. It takes varying forms, but the essential argument is:

Immigration makes the economy grow — so what? I’d rather be poor. I don’t care about the connection to the economy, I want Britain to stay British.

This is a false dichotomy: there is no need to eschew the economic argument even if you also oppose mass immigration on other grounds. More than that: this argument is flawed analysis, and worse strategy.

As we have seen, the argument that immigration makes the economy grow may still be the default in political conversation, but it is built on sand. Immigration is not making Britain’s economy grow, at least not in any way that benefits British people, and in fact is likely making it worse. To refuse to argue over immigration’s economic impact is to cede ground which is clearly and obviously available for those who want Britain to stay British for whatever other reason. In political terms, too, it is on the economic impact question that the median voter — nervous of arguments about culture and ethnicity — can be engaged.

Leave aside the politics though. If we want Britain to stay British, then the country needs to prosper; decay and decline in the economy will soon mean opening our country further to foreign cultural domination. The evidence set out here is that immigration isn’t helping our economic growth, but also that it has become institutionalised within our economy.

If we are to reverse Britain’s relative decline, we need to reshape our country to address the flaws exposed through mass immigration, not just created by it. There are countries in Eastern Europe which are ethnically and culturally homogeneous, and have had many years of negative net migration. Yet few want to go there, and many of their most talented people have departed for foreign lands, leaving their home behind because it offered such little hope. Simply turning our backs and refusing to consider the economic questions will not help us avoid such a fate.

Image rights: Ggia, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

This article was written by Thdhmo, a regular Pimlico Journal contributor. Have a pitch? Send it to pimlicojournal@substack.com.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing. If you are already subscribed, why not upgrade to a paid subscription?

The ONS’s data on this is increasingly flakey, but HMRC data on foreign nationals has it at 16.2 percent of all PAYE employees, and ‘country of birth’ includes some who have become ‘administratively British’, so it seems broadly accurate.

In some cases, they might choose neither — and that’s a good thing.

Arrow and Capron’s 1959 paper is used for lack of alternatives. Since then, ‘shortages’ arguments aren’t very respectable in economics: the word is mentioned only once, obliquely, in the US National Academy of Sciences’ 643-page epic on immigration economics.

There are other variables, for example the planning system and the energy system contributing to great cost and volatility.

The difference is in mid-skilled roles, such as administrators or skilled trades, which are dominated by natives. It is worth noting that this is very much the ‘good’ story of skills complementarity sometimes used to justify immigration as an economy policy — it’s just that it has bad fiscal consequences.

The OECD’s 2019 PISA test data for England, taken by school pupils, show that these effects are not confined to the workforce; reading scores for first and second generation immigrant pupils are also significantly lower than for non-immigrant pupils.

Anyone who seriously believes that the immigration of largely non-White, essentially uneducated, largely without much in the way marketable skills types, is going to be a benefit to any Western country is out of his/her mind. The destruction of Western nations from within via such an OBVIOUSLY inappropriate sort of immigration, as well as other insidious and nefarious means, has long been in the plans of the International Zionists. Have any doubts? Check out, 'The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion.' These Satanic plans have been, 'in the works,' for around 200 years. The world needs to understand CLEARLY that Zionism is equal to Satanism. ...and then do whatever necessary to rid the world of Zionism and Zionists!