Electoral reform doesn’t have to be the preserve of the left

Time to fracture the right

Electoral reform, particularly the idea of replacing Britain’s first-past-the-post system with a form of proportional representation, is largely the preserve of Britain’s alternative left-wing parties — although, it should be noted, not entirely.

The argument against first-past-the-post (FPTP) is that, whilst smaller parties can win a huge number of votes nationally, they are typically unable to coalesce their support in one geographic area. This means that the huge number of voters who vote for smaller parties are effectively disenfranchised. PR, they argue, would fundamentally change that by enabling a fairer and more accurate representation of national sentiment. They argue that any system in which it takes Conservatives 38,000 votes to win a seat on average, Labour 50,000, the Lib Dems 336,000, and the Greens 866,000 is structurally unfair. PR would mean that the government would be more likely to represent the majority of voters, eliminate ‘unequal’ or ‘wasted’ votes, and ensure MPs better represent their constituents politically.

But does it have to be left-wing coded? The alternative left-wing parties generally assume that there will mostly be a continuation of the existing electoral situation, just with more ‘equal’ and ‘fair’ representation (meaning more seats for them). But it’s possible, indeed likely, that a move towards PR would significantly alter the electoral landscape — and it’s entirely possible that the right would be the main ones to gain. Which leads us to ask: is it time for the right to argue for PR?

In Ruling the Void, Peter Mair took a look at the state of Western democracy. His contention was that the triumph of democracy through the twentieth century was a hollow one, in which democracy was ‘steadily stripped of its popular component.’

A key part of this was the death of mass participation in political parties. Whilst they had started off as genuine mass movements — often inextricably linked with other institutions of belonging, such as unions or churches — the political parties saw a dramatic fall in membership in the ’80s and ’90s. By the millennium, the average total party membership in a Western democracy was around 5% of the population, approximately a third of what it was in the 1960s. In four decades, Britain had lost 1.2 million party members. This accompanied a decline in trust in politics, the rise of alternative ‘protest’ parties, and a decline in turnout at elections.

The problem is that parties are integral to the British political system. They give voice, integrate and mobilise the public, and articulate and aggregate interests, translating these into public policy, recruiting and promoting political leaders in the process. Mair argues that the decline of participation in political parties has led to a risk of us losing the necessary connection between ruled and rulers.

As political elites withdrew from the populace, they replaced this complex interface between electorate and representative with the ‘experts’: allegedly non-partisan technocratic specialists, embedded in supposedly accountable institutions of state, who make decisions that are beyond the capacity not only of the ordinary voter, but often also of the politicians they elect. This was exemplified by New Labour’s ‘politics of depoliticisation’, and is the intellectual underpinning of the current hub-based Blob government. The populace are stakeholders to be engaged, not electors to be represented.

This disconnect between rulers and ruled provided politics with a feedback loop that no longer exists. Whilst only 5% of the electorate hold economic and socially liberal views, as a result of this severance it has become the consensus inside Westminster, and has continued unchallenged since the end of Thatcher. Even the two relative political outliers since — Truss and Johnson — did not stray far. Johnson, who campaigned on a platform approaching populism, could not help but rule as a social liberal; a key part of Truss’ plan to ramp up economic growth was to ramp up immigration, including throwing the doors open to unrestricted migration from India.

The long-term effect of this is a populace that has never been more turned off by politics. The largest voting bloc in Britain is now ‘Don’t Know’. The vast majority of people feel there is no party that represents them, in particular the so-called ‘Red Wall’ voters, who lent the Conservatives their votes, only to see them piss away a historic majority by failing to do anything they’d been elected to.

This missing feedback loop can also been seen in the lack of the existence of a more right-wing alternative. In the face of a historic Conservative collapse, Reform and Reclaim stand to gain… absolutely nothing. Not a single seat. Both parties are creations of the existing political system, ensconced entirely within the world of Westminster. Neither Fox nor Tice have any actual understanding of their voters; alternative right-wing politics has been transformed into messaging campaigns based on caricatures of their electorate. Perversely, much of this messaging simply repurposes the negative caricatures drawn by establishment and left-wing commentators in the immediate aftermath of 2016, which painted Brexiteers — and especially white, working-class, formerly Labour-voting Brexiteers — as fuelled merely by ressentiment.

Both parties, for all their funding and media profile — both leaders, until recently, had regular slots on GB News, which is watched predominantly by their target voters — are yet to break 10%. The Conservatives are about to be decimated, and as a result of that destruction the right will be cast out from Parliament.

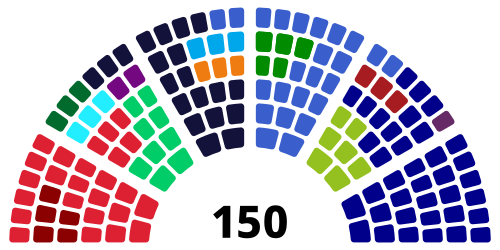

It is right elimination, rather than replacement, on the horizon. Britain is almost unique in Europe in this respect: while many other old, establishment right-wing parties are also experiencing seemingly terminal decline, instead of the consequence of this being an entirely left-wing political landscape, much of the rest of the continent is seeing right-wing governments formed by new or newly resurgent parties. Britain is also almost unique in using first-past-the-post. These two things are not unconnected. Under FPTP, the ‘broad church’ approach of the Conservatives means the party is able to absorb multiple strains — the vast majority, in fact — of British right-wing thought, from dripping wets to what Novara Media would call ‘far-right’ (they believe in reducing immigration somewhat).

Even the group that is most closely aligned with the voice of voters, the so-called ‘New Conservatives’, remains inside the Conservative Party — and outside of power. Politicians advocating for government to do what matters to the electorate — for instance, reducing immigration — have to battle on every issue against the hegemonic and entrenched liberalism within Westminster, spending scarce political capital as they do so. Without an infinite amount of political capital they must choose their fights, and the biggest issues are often simply left alone. How can anti-immigration Tories like Braverman simultaneously fight half her own party, the Home Office, the Blob, and every business that is entirely reliant on a rentier model of low-wages to sustain themselves? She has chosen to raise it as a political issue, but when the business lobby is screaming at every Cabinet member that their sector will instantly collapse without more migrants, and with two-thirds of the Cabinet not minded to care anyway, how likely is she to win?

Meanwhile, ambitious young right-wingers have to choose between openly airing their conservative views and having their career stall as a result, or moderating them to ensure career progression through the liberal gatekeepers of CCHQ. In order to ensure a pliant party, CCHQ staffs the parliamentary party with unideological drones, glorified councillors who do not have sufficient intelligence or bravery to question the Westminster Consensus.

And here is PR’s benefit to the right: it will break the domination of the right-wing bloc vote by the Conservatives, and re-establish the feedback loop between rulers and ruled. Let’s look at Europe. We are warned that PR would unleash ‘chaos and extremism’, but is it extremism to give people what they want? Those that have done even the most basic of research are aware that parties like the AfD are no more extreme than UKIP, and the Front Nationale would probably win every British election from here until the end of time.

These kinds of platforms are prevented from coming forward because, under FPTP, the Conservatives have a hegemony over the right-wing vote whilst also being able to poach votes from the centre by building a moderate, centre-right electoral platform. But, as the last thirteen years have proved, once in Government, whilst the Conservative Party’s stated preference is conservative, its revealed preference is centrist-liberal.

Many leftists labour under the misapprehension that our ‘fragile electoral ecosystem’ will continue to operate exactly as it does now. They believe that power will simply accumulate on the left, and nothing will change on the right to alter this imbalance. ‘One of the main points of opposition that we come up against is the idea that a proportional voting system would allow the radical right to infiltrate mainstream politics, but these fears are exaggerated’, wrote one Morning Star journalist. This is a stupid mistake — but then again, in their defence, they are generally very stupid.

One only needs to look at previous British elections for an indication that PR could spell a new moment for the right. European elections, which use PR, saw thumping victories for UKIP in 2014 (after a forgotten second in 2009, and third in 2004) and for the newly-established Brexit party in 2019.

But PR is not without problems. It’s a matter for discussion what impact it would give the huge ethnic bloc votes we have imported through our unrestricted immigration policy. Would we be willing to accept the presence of a ‘Party of Islam’ within the House of Commons, or is it more likely that a left-wing alternative party would hock their votes to sectarian interests in order to climb up the ladder? This bloc is already capable of delivering Westminster majorities, however, and has given us numerous MPs who seem solely active on issues related to whatever ethnic or religious bloc they are dependent upon. It is questionable whether it would be a significant change in anything other than saying the quiet part out loud.

It is possible, too, that a centrist coalition could hold on. The famously unstable politics of pre-Fascist Italy, in which a single party rarely had a majority, may give us pause. Giovanni Giolitti — the longest-serving democratically elected Prime Minister in Italian history — kept himself in power through trasformismo, the political art of making a flexible coalition of government which isolated the extremes of the political left and the political right. In Mussolini: A New Life, Nicholas Farrell describes how trasformismo operated:

Giolittian horse trading… ensured a workable coalition government. The ancient regime had governed by means of alliances between myriad shoals of current and tendency, in a state of endless transformation, pasted together by patronage rather than policy.

Trasformismo, however, underlined to the electorate the fundamentally broken nature of the Italian political system. Mussolini’s success lay in decentralising Italian democracy, bringing it out of parliament and into the piazza — that is, restoring the connection between ruler and ruled.

Some important obstacles to the success of the British right will soon be removed. Once out of power, the Lib Dems who joined to get into power under Cameron will not stay, and new ones have not joined as a result of Brexit. The New Conservatives may be emboldened to stand up and say what they think — and if they fail to win power, they may even be tempted to start a new party.

If Sunak’s return to Sensible Cameroon Centrism leads them to a historic collapse, there will be a new head atop the rotting corpse of the Conservatives. It remains to be seen if the lifeless corpse is worthy of reanimation.

This article was written by an anonymous Pimlico Journal contributor. Have a pitch? Send it to pimlicojournal@substack.com.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing. If you are already subscribed, why not upgrade to a paid subscription?