Against 'food nationalism'

And 'food multiculturalism' too

Pimlico Journal promotes right-wing thought. The definition of what constitutes ‘right-wing thought’ becomes much more vague once we look at cultural — rather than directly political — issues. Existing and ‘fitting in’ as a right-wing person has always been easy, unlike as a left-wing person. You aren’t required to have read whoever the right-wing equivalent du jour of Joan Didion or Ocean Vuong is, nor know which brands one was supposed to boycott this week for supporting Israel. The whole idea of the Left as a bunch of Columbia undergraduates sitting in a fair-trade, eco-friendly, minority-run ‘bodega’, debating the ‘important issues’ while simultaneously using ‘culture’ to try to catch each other out for not being up-to-date enough on the latest developments in Woke, in a perpetual game of one-upmanship, demanding that you ‘educate yourself’ is a bit of a hackneyed stereotype. But is it wrong?

If you aren’t, in fact, filled with envy at the idea of living like our counterparts on the Left, then I hope you will join me in my quest to convince others to stop using food to criticise cultures that they don’t like. By rejecting this, we can prevent ourselves from turning our free-wheeling right-wing political movement into a heavily-policed cultural club.

Of course, any right-thinking (and Right-thinking) person is already tired of hearing how Mexican food means the United States needs open borders. Similar discourses exist in other Western countries: the Netherlands with Indonesian food, Britain with Indian food, Germany with Turkish food (though this is even less convincing), and every country on the planet for the Scandinavians. We could call this rhetoric ‘food multiculturalism’. We all know the line: ‘You hate immigration, but your car is German [almost no-one in Britain has ever had a problem with German immigration, and we don’t need to import the people with the car anyway], your fashion is Italian [ditto], your democracy is Greek [ditto], and your food is Indian [which is where they ‘get us’, suddenly throwing in a third-world country, and demanding we need the people and the recipes].’

The Right’s perceived need to respond to this pathetic argument is probably the ultimate explanation for why food now occupies such a prominent place in cultural discourse. By responding to this shallow discourse in kind — by accepting that yes, food is an important cultural signifier — the Right does nothing but play into their hands. This culture war over food is, for sure, one that the Right can win, but it’s better to refuse to even acknowledge it, beyond doing the easy job of rejecting the line recited above. Do we really want to spend hours upon hours agonising over what sort of food qualifies as ‘slop’, or should we — in what I would argue is much more in line with a genuinely right-wing worldview — just shut up and eat?

To be clear: there is nothing wrong with having strong opinions on food per se: the culinary world is a rich and colourful one. But turning it into an explicitly political discourse has not even once yielded any gastronomic insight. Similarly, nothing of value has arisen from the debates of the Columbia students I have parodied above, who are all no doubt still sitting in their ‘bodega’, attempting to police and gatekeep pop culture (‘anyone who thinks Mean Girls is a bigger feminist masterpiece than Jennifer’s Body is uncomfortable with the way female sexuality has been horribly abused for the benefit of the male gaze!’). Politics is not, in general, actually ‘downstream of culture’. You aren’t achieving anything, and neither are the leftists. Food should be discussed as food, nothing more and nothing less.

The worst offender, of course, is the bona fide ‘food multiculturalist’ who decides to try their hand at a bit of pseudo-intellectual ‘cultural history’, and argues that, if we go back far enough, everyone’s food is actually from elsewhere. Fish and chips, we are told, is apparently ‘Portuguese’, whatever that means. Despite ‘food multiculturalism’ being an idea almost solely found on the Left, this particular argument is in fact deeply conservative in its need to argue from the past, i.e., ‘tradition’ (Burke would be proud!). Within every right-wing person there are two wolves, and one of them is a raging conservative that can’t resist the temptation to engage the Left whenever they make historical, rather philosophical, arguments. I suppose Scruton was right with regards to where a fixation and overreliance on historical arguments inevitably takes us.

It hardly even seems necessary to say this, but the logic of ‘food multiculturalism’ is absurd. ‘Now we have the recipes…’, while supposedly a ‘joke’, is in fact a perfectly valid response most of the time. We just need the ideas and the ingredients, both of which can move around without the people. If training is actually required — which is rare — our own people can go abroad and learn what they need, whether that be studying under an itamae in Kyoto or at Le Cordon Bleu in Paris. Let us also ignore the fact that this basis for multiculturalism — even if it does make up for all the negative effects of immigration, which is doubtful — would suggest very limited immigration, targeted at chefs (whatever Britpoppers might think, Indians don’t all have an innate ability to make great curry) from as many different countries as possible, with hard caps on numbers from each culinary region. We don’t need a free-for-all, especially from countries where it is obvious no-one is interested in their food anyway. We should also be ruthlessly be selecting our immigrants based on their culinary abilities, replacing those who don’t make the cut: even assuming we can’t just get a white British person to do it, why should we have Pakistanis making our kebabs when it’s obvious the Turks are much better at it?

But beyond this, do you become just that little bit more ‘Japanese’ because you enjoy sushi? Or do the Japanese become just that little bit more ‘Italian’ because they now eat pasta? Of course not. This is only the most shallow form of ‘culture’; so shallow, in fact, that it is dubious whether we should even classify it as ‘culture’ at all. It is obvious that you can enjoy foreign cuisine with no change whatsoever in your fundamental being. Whatever the narcissistic multiculturalist may think, there is no genuine ‘cultural exchange’ taking place when you eat your vindaloo, pilaf rice, and garlic naan.

It is no accident that almost without exception, food is the most rapidly changing element of any ‘culture’. After all, in food, the great majority of people enjoy some degree of novelty. This is not usually true of more fundamental forms of ‘culture’ such as (say) family structure and relations. New ingredients are usually fairly rapidly incorporated into food once they become available. Very few popular dishes are more than two centuries old in their current form, and most are much newer than that. European food before the discovery of the New World is almost unrecognisable: for those who could afford it, loads of sugar — which was seen as a ‘spice’, and used a lot in savoury dishes — black pepper and, more unusually from the perspective of 2024, ginger, saffron, and cinnamon; but lacking such basic crops as potatoes and tomatoes, let alone ingredients like cocoa and vanilla. Did the Europeans really change as rapidly as their food? Did the Irish become a little bit ‘Indian’ when they started making mashed potatoes? Of course not, and insofar as they were changed by the New World, it had nothing to do with the food they were eating.

As such, the Left’s concept of ‘food multiculturalism’ is easily dispatched with. But what about the Right? How do we think about food? And how should we think about food?

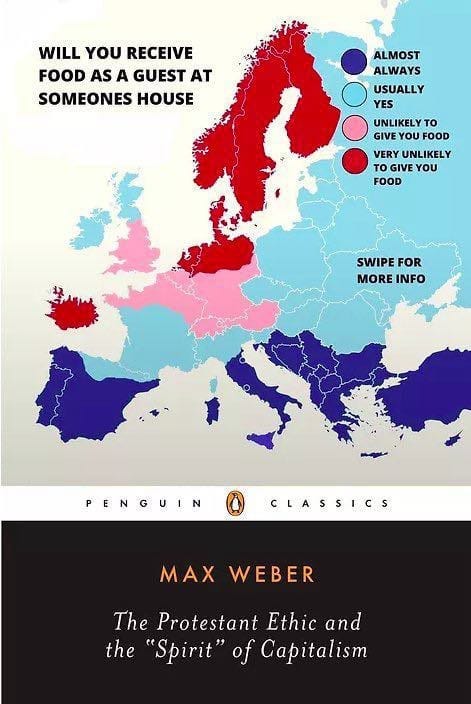

On the Right, the ‘food discourse’ is generally divided between two camps. There is the no-nonsense type, best exemplified by the image below:

Which is, I think, fair enough.

But then there are these sorts of deviant right-wing positions held by the type of people who have a rather weird relationship with food and ‘food culture’ (this term needs to be banned), and how it relates to right-wing forms of nationalism more generally. Let’s call this ‘food nationalism’. I think we can put this concept into three main categories.

I. We have bad food, and invaded the world because of it!

I’m sure you’ve all heard it by now: the first of our three ideas is that because (say) British or Dutch food was so bad, so lacking in spice and flavour, our men went off to colonise the entire world, taking the flavours back home with them. Some of these people are proud of the prominence of foreign cuisine in their home country, thinking it shows them to be ‘cosmopolitan’, and thus superior to people who stick to their own food, whether out of stubbornness or because they have no choice. In short, it’s an attempt to accept the Left’s premises, but turn them into something that seems to be ‘right-wing’ and ‘nationalist’.

Obviously, this is usually flippant — and annoying, associated as it is with a kind of blue-jumpered ‘Spiffing Brit’ imperialism — rather than serious, so let’s just move right on.

II. We have bad food because of our ‘austere’, Calvinist-influenced culture!

The second, much more serious, idea is the claim that the reason that the food in countries like Britain and (especially) the Netherlands and Scandinavia is ‘bad’ is because these cultures are ‘austere’; profoundly influenced by Protestantism, or more specifically by Calvinism or Pietism. This is said to have equally promoted individualism and freedom, and abstemiousness and simplicity. In this idea, the reason why the Netherlands is rich is because their peasants did not take a two-hour ‘lunch break’ to cook delicious food for the family (which certainly did not exist over there) — instead, they worked all through the day! By this point, this is probably the standard ‘defence’ of Dutch (though not British) food.

Some of this discussion has moved towards shaming those Britons — often alleged to be ‘post-liberals’ — who would deign to try to revive English ‘folk’ traditions. There has long been an understanding on the British Right that since Britain was uniquely modern from at least the eighteenth century, advanced even by European standards, it did not need to predicate its identity on elves, fairy stories, or precious rocks. Britain, it could be said, skipped the ‘Romantic Nationalism’ of the nineteenth century. While this sort of folksy nationalism used to be an elite affectation in the nineteenth century, and there is nothing wrong with it per se, it has now transmogrified into something of the Third World. How this relates to food may not seem intuitive, so let me explain.

In this reading, we aren’t allowed to have good food because this would somehow compromise the modernity of our ‘Protestant’ culture. And all this is really down to the fact that when it came to weaponising food in political discourse, the Woke and the Third World got there first, setting the table for us. Countries that had little fundamentally going for them were among the first to do this: ‘You guys have schools and roads? Well, I bet your grandmothers were awful and cold and didn’t know how to cook! Because, if they did — oh boy — you wouldn’t be able to do much else but eat!’

Tourism page after tourism page will sing the praises of various Third World cuisines (barring those of certain African countries, that is; no-one has yet tried to rehabilitate ‘fufu’): ‘Discover the flavours of x.’ Countries like Spain and Italy, who have always been known for their good food, have just continued promoting their cuisine as they always have. Meanwhile, the Eastern Europeans, opportunistic as ever, decided they were just about still poor enough to have ‘ethnic food’ and join in on the grift.

Thanks to Eastern European tourism pages and self-hating people from these countries, merely being European no longer automatically prevents you from falling into the ‘food-so-good-it-must-mean-we-are-poor’ trap. Why not pretend you’re the scion kind of some ‘ethnic’ spice culture if it means getting more money from tourists? I guess the only explanation for why the Eastern Europeans didn’t invade the world was that their boiled pork shanks and cornmeal porridges were just so good that they didn’t need to obtain any spices, given that spice more or less does not exist at all in any Eastern European cuisine, no matter how southerly one goes. Shame the British overboiled theirs.

Do we have any evidence that the Hungarians or Romanians took three times longer to enjoy their pork shank than their Dutch counterparts, who ate rather similar food, except for the fact that they were poorer? What evidence do we have the Hungarians or Romanians historically enjoyed their food more than the British, except money-grubbing tourism agencies that want to convince you that Eastern Europeans invented the concept of sitting with your family and chatting over a hot meal? The food itself certainly provides no evidence of this: it’s hard to find a simpler, more no-nonsense cuisine.

Has anyone bothered to observe the many, many similarities between Eastern European food and the food of such countries as the the Netherlands? There is nothing in Polish cuisine that would have startled a Flemish peasant, nor anything in Serbian food that would have startled a Bavarian peasant. If you are European, there is nothing in general remarkable about any other European cuisine, especially at the ‘folk’ level, with most differences ultimately coming down to what people could or could not grow. If the explanation for the ‘bad food’ of the Netherlands was ‘Calvinism’, then you’d expect it to be a bit more different from the food of other European countries with relatively similar climates.

It is really only the Woke who used to seriously argue that that there is some kind of negative relationship between the taste and prominence of food in a culture and that culture’s level of development (development which, in their view, is only achievable through exploitation). Why copy them? No: being a ‘Calvinist’ does not make you immune to gluttony, leading to increased savings, and thus more investment and increased national wealth. And if ‘asceticism’ (or whatever word you prefer) were truly the cause of modernity, then the Industrial Revolution would have started in the Eastern Orthodox world, where people fasted in some form for four-sixths of the year, and where much of the cuisine is influenced by this fact (see, in particular, Greek food).

It should be observed that the same standard is never applied to ‘drinking culture’. Many corners of the British Right place an undue emphasis on ‘drinking culture’. A country that is said to lack it is automatically suspect and considered poor — often forgetting the fact that relative to Brits, the wealthy Scandinavians and Dutch (much like many Eastern Europeans) prefer to drink at home, rather than at pubs where one is deemed to engage in ‘drinking culture’. While the genetic capacity to safely process large quantities of alcohol is inarguably a hallmark of ‘Europeanness’ from a biological standpoint, a theoretically rich and elaborate ‘drinking culture’ can obviously be just as time-wasting and unproductive as a rich and elaborate ‘food culture’, if not more.

While in the present day there might be a connection between being a good chap and liking the pub, all things considered, the ‘drinking culture’ surrounding pubs is hardly an antidote to frivolity and ritual. I’ve been told that a ‘real’ pub does not serve food. I must say, our Protestant forebears would not be very impressed by this lack of convenience. I’ve also been told that the essence of the pint of ale or lager is that it is low enough in alcohol and large enough in volume for one to be able to hold something while you sit around and chat for hours. Not very efficient compared to the more ‘European’ preference for a rapid succession of shots. At least the Italians with their midday espresso rituals are getting their energy boost for the day from it, instead of rendering themselves drunk and thus incapable of working.

III. Our food isn’t bad — we were so rich that we didn’t need ‘slop’!

The third idea, by contrast, self-consciously rejects both the right-wing claims of (I) and (II), as outlined above, and those of the Left. Rather than accepting the left’s fundamental premise, they will deny that Dutch, Scandinavian, or (especially) British food is bad; instead, they will defend it as being actually good, and, more specifically, argue that this food is in some way defined by the country’s wealth.

For the record, I do somewhat sympathise with this position, as I happen to think that both Dutch and British food, contrary to popular belief (especially of the former), are pretty great. Although I’ve not had the pleasure of trying out Scandinavian or Baltic food yet, I’m fairly sure it’s not actually bad, despite the stereotypes. Even beyond New Nordic cuisine — e.g., Noma — I’ve recently been fascinated by the Michelin-starred restaurant KOKS, previously located on the Faroe Islands, and now (temporarily) in Greenland. The fact is that European food is generally great, and there is no reason to endlessly contemplate why that is. It’s almost certainly nothing to do with anything particularly deep-rooted, or at least something that is both particularly deep-rooted and identifiable with only one European country. Perhaps we are better off citing climate plus some degree of random variation, and leaving it at that? It seems clear enough to me that what differences do exist usually have little to no connection to a country’s ‘culture’, properly defined.

People who support this particular response begin by claiming (not entirely without merit) that in Britain, a greater part of society had access to good-quality produce and copious amounts of meat. As a result, they continue, British cuisine moved in a particular direction. It eschewed lots of spices and sauces, instead letting the ingredients ‘speak for themselves’. Spices and sauces, it is further argued, are often used to cover up the poor quality of the meat in many foreign cuisines.

It is from here that the increasingly omnipresent ‘slop’ discourse seems to have been born. You see, beef and gammon and Yorkshire puddings and roast potatoes are solid, unlike most foreign food, which is slop.

If this was just the ravings of an autistic boy who was sensorily perturbed by all liquid food, with no politics behind it, then this would be tolerable, but it is not. Nowadays, it has become a catch-all insult on the Right. It has gotten to the point that when calculating a ‘Slop Index’, it is often not just the food itself that is taken into account, but also the way in which food is enjoyed: ‘food culture’. Once you’re deemed a ‘food culture’ (so long as you are not Japan or France), you are screwed. You can have the most hardy food in existence, yet the second someone catches your countrymen sit around a table with sharing dishes, you could just as well be eating ‘slop’, because your cuisine will be spoken of in an eerily similar manner. North German and Polish cuisine is not fundamentally that different, both being fairly utilitarian and from a similar climate, but they are spoken of very differently owing to their supposedly distinct ‘food culture’: one is associated with workmanlike, austere Prussians; the other one is associated with ‘babushkas’ in headscarves picking potatoes shaped like their noses. The truth is that the term ‘food culture’ (and its sister, ‘drinking culture’) are nothing more than pretentious nonsense. Anthony Bourdain killed himself after he realised this.

If there is one thing that I hope that readers will take away from this article, it is the need to retire the word ‘slop’. I don’t want to be pedantic, but what even is ‘slop’? Why is French onion soup and gazpacho not ‘slop’, but prawn curry is? If all curry is ‘slop’, then why isn’t Japanese — the Japanese always seem to inexplicably escape from these critiques — curry also in this category? Why do ‘sloppy’ pasta sauces not make pasta dishes ‘slop’, given that curry is also not generally eaten without rice or naan? What about porridge, or poutine, or mash?

Conversely, if the ‘meatiness’ and/or ‘solidity’ of national cuisine is the ultimate test of cultural respectability, then it would be difficult to find a European country with a more hyperborean cuisine than Albania. Cow’s head, liver parcels, grilled meat, and french fries, with nary a spice to be found. You would be hard-pressed to call any of this ‘slop’, yet culturally, Albania remains the black sheep of Europe.

Is sugary food ‘slop’? That would be strange, given that pastries and sugary goods become more popular the more north you go. Denmark is famous for butter cookies and sweet pastries. You don’t find anything like this in Turkey, where savoury poppy-seed bagels and salty cheese parcels are more popular. Or maybe ‘slop’ is just one of those ‘you know when you know’ things; or perhaps people just like applying this label arbitrarily because the word sounds funny. An undeniably solid Domino’s Pizza or Big Mac can now be ‘slop’, just because it is mass-produced and some people don’t like the taste. Nowadays, even television shows and music can be ‘slop’, yet there is no consistency in how this word is applied: Marvel is ‘slop’, but what about Taylor Swift?

Can we not agree that all three of these right-wing responses to ‘British/Dutch food is bad’ — even the third, which is far more legitimate though still, in my view, flawed (or at least almost always leading to the annoying ‘slop’ discourse) — just have far too much thought put into them? We’re talking about food here. We’re all agreed that ‘food discourse’ should have zero impact on our policy towards immigration. But do we also agree that ‘food discourse’ should have zero impact on national identity or self-worth? I wouldn’t be so sure.

When will we accept that there is no such thing as a ‘right-wing food reviews’ — just ‘food reviews’? We are not the Left. We don’t need to cultivate our own ‘lens’ with which we interact with the entire world. If there is one mentality which unites all readers of Pimlico Journal, it is a contempt for the self-righteous busy-body in all forms: whether that be the middle-aged NIMBY, the yellow-vested ‘Covid marshal’, the self-righteous local government commissar, the Woke university student with blue hair, or the plump, hypocritical Third World matriarch. Making our own ‘us-versus-them’ lists of acceptable consumption — television shows, holiday destinations, food, et cetera — is an aberration. We should not let the Left turn us from a group of rational, anti-immigration, pro-growth, freedom-lovers into the sort of people who spend most of their day tutting whenever someone fails to adhere to their petty ideas of ‘social propriety’.

I appreciate that this article is rich in irony. Here I am, writing to tell off those who seek to police others’ attitudes towards food, drink, and travel by politicising them, yet at times in my article I have come close to breaking my own rules and carving out a new social constitution, in which the concepts of ‘slop’ and ‘food culture’ and ‘drinking culture’ are now verboten. I must confess that I cannot fully explain myself out of this, leaving me with no choice to heartily thank all those Pimlico Journal contributors who do the genuinely important political work; the articles that occasionally end up getting read by those with influence. My articles, by contrast, are all ‘cultural’. What I insist on is that there is no correct ‘right-wing’ way to live one’s life — there is no generalised right-wing cultural ‘lens’; no ‘correct’ cuisine to know about, no ‘correct’ country to like visiting on holiday. Nothing good can come out out of attempting to use shame or promoting herd mentalities in order to push one’s own tastes; what ultimately unites us all is our politics, not our taste. Some cultural commentary is profound; most of it is not. But all of it is of less use to our political cause than even the most debased rigmarole.

I believe a good part of this "slop tier list" nonsense is generated purely by the lowbrow section attracted to the right simply due to edge and empty reactionary sentiment. They don't care to explore Evola and figure things out, they want to get the correct "take" to parrot.

Similarly, they don't care about food quality, for that matter most can't cook to save their lives. They just use it as a moronic way to go to bat for their chosen identity, whether it be "medchad", "wholesome AMERICAN protestant" or what have you.

I'm not British, but I once had the occasion to hear one of these types rant about how "bri'ish" blood pudding is disgusting. I then served him my own countries' blood sausage variation a few hours later, and he allegedly loved it. Go figure

There's no right-wing equivalent of Joan Didion, she's already right-wing!