A brief history of the state pension

A bipartisan bilking?

I hate the ugly, hate the old,

I hate the lame and weak,

But more than that I hate the dead

That lie so still in their earthen bed

And never dare to rise.

I only love the strong and bold,

The flashing eye, the reddening cheek,

But more than all I love the fire

In youthful limbs, that wakes desire

And never satisfies.

-Enoch Powell

It is now a commonplace to label Britain a ‘gerontocracy’ and lament the yoke the elderly have over the young and the working. ‘Based’ YIMBYs and the denizens of ‘Wonk Twitter’ scramble to denounce the Triple Lock and break out the cliché of ‘Fourteen Years of Conservative Government’. This anti-gerontocratic sentiment is often just a manifestation of the sub-political meme of boomer-bashing — it is all too telling that boomers are typically white-coded — but can be, at its most developed, an awareness of our deeply unsustainable dependency ratio, one of the direst issues that Britain faces.

There is much to be admired about this political tendency, not the least because it breaks away from the still-latent Britpoppery by offering a political critique distinct from ‘the bankers, the bonuses’, and appeals directly to the economic interests of the youth. However, disappointingly, it maintains a concern with seriousness and respectability that will prevent it from ever straying too far outside the Overton Window. The typical anti-gerontocrat is a ‘Policy Analyst’ in his mid-thirties — still renting in Zone 4, still waiting to be parachuted into a Tory safe seat.

This caution manifests itself through a tendency to neglect the other contributor to the dependency ratio, the young but economically inactive; Britain’s large and growing underclass, many of whom are recent immigrants. Corrections to this neglect may be found in the pages of this journal. What I wish to focus on here is the often unstated assumption of the anti-gerontocrats — namely, that the privileging of the interests of the elderly over the young is a uniquely Conservative policy, and that Labour, as the presumed party of the youth, will rectify this imbalance.

There are stock responses to this assumption — for example, that Keir ‘Kriminal’ Starmer is the same age as the ghoulish Alec Douglas-Home when he contested the 1964 election, so can hardly be described as some sort of youthful radical. Here, I will rebut this assumption more thoroughly through an analysis of the history of the state pension.

The Early State Pension

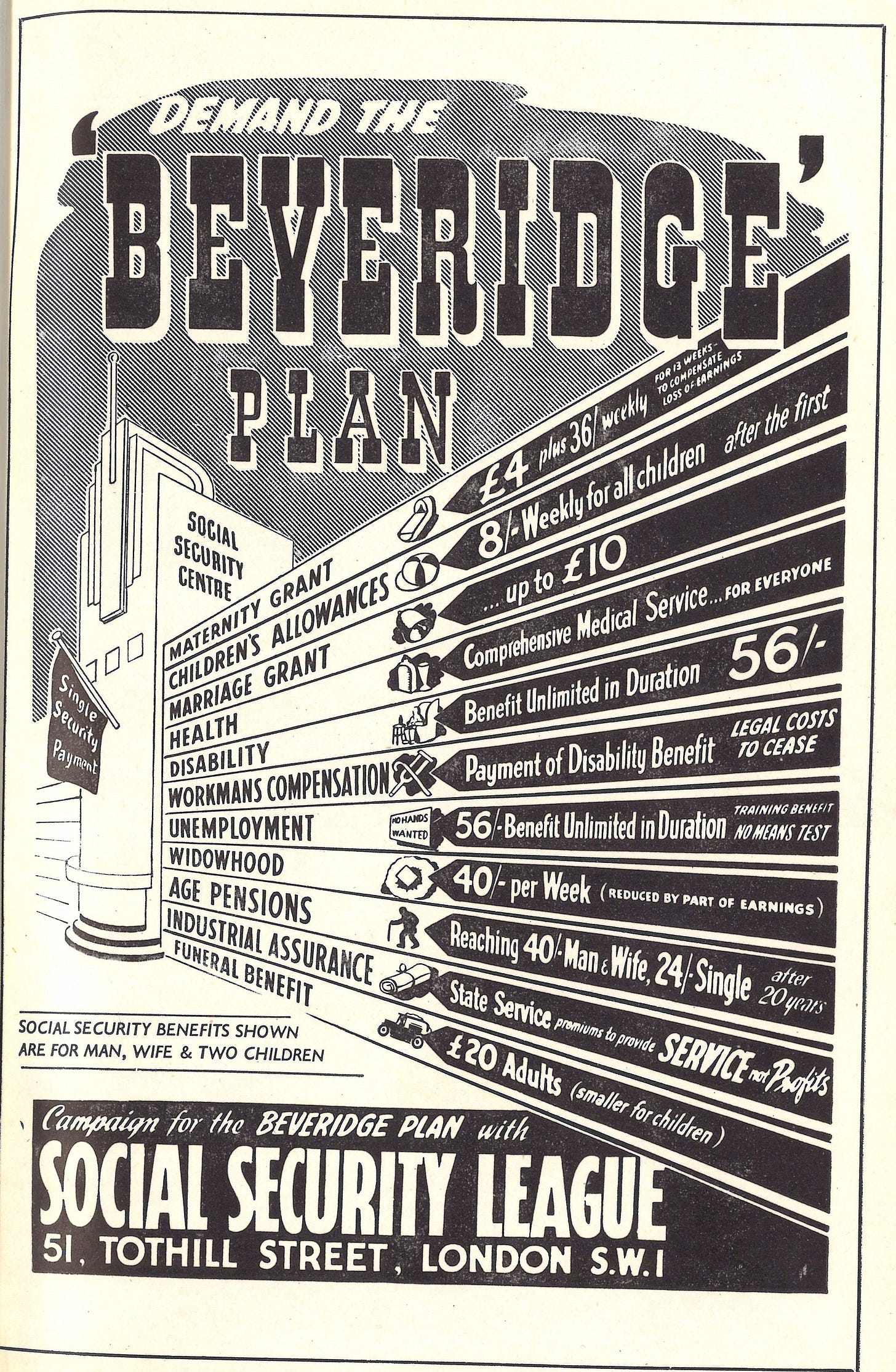

The ideal of a state pension for all was most famously articulated in the celebrated Beveridge Report of 1942. The report directly led to the introduction of the Basic State Pension (BSP) in 1946 by Attlee’s post-war Labour government — though, as I shall argue, there were significant differences between the pension imagined by Beveridge and the one actually implemented by Attlee.

There had been important precursors to the BSP. Notably, the reforming Liberal governments of Asquith had made a state-provided pension a flagship policy. The Edwardian Liberals had been motivated by manifestly philanthropic reasons: awareness of the extent of old-age poverty had grown in the late nineteenth century, primarily due to the work of the social reformer Charles Booth, whose survey into poverty in London had revealed that the elderly were the largest group of paupers.

However, the 1909 pension differed significantly from the scheme envisaged by Beveridge. Although the Liberals would introduce National Insurance in 1911, the pension would remain separate and non-contributory. Coverage of the pension was strictly limited by stringent means and character tests, and was intended solely for the poorest. By contrast, Beveridge’s scheme was universal, and linked to National Insurance — any British citizen would receive the pension upon retirement so long as they had made National Insurance Contributions (NICs) for the necessary number of years.

Instead, the true precursor to the BSP may be found in the reforms to National Insurance in 1925, made by Neville Chamberlain as Minister for Health. Workers in insurable employment, and their employers, would make regular NICs. (Before the war, not all employment was insurable — generally, only industrial workers were insured.) In exchange, they would receive sickness and unemployment payments, and, as a result of Chamberlain’s reforms, a pension upon retirement.

These reforms were made for primarily pragmatic reasons: concerned by the upheavals in Russia and the widespread industrial unrest (and stubbornly high unemployment rates) in inter-war Britain, Chamberlain hoped that a contributory pension would mollify discontent. He was no doubt inspired by the insurance-based pension introduced in the German Empire in 1889, which was motivated by a desire to reduce the threat posed by the Social Democrats.

Beveridge and the Basic State Pension

Although the design of Beveridge’s pension scheme would come from Bismarck, by way of Chamberlain, its motivations were closer to the woolly moralism of Asquith and Lloyd George, rather than a hard-headed response to the threat of Bolshevism. The philanthropists of late Victorian and Edwardian England had argued that the Poor Law of Chadwick was cruel and outmoded. Lloyd George shared these concerns — notably, he legislated that the pension was to be collected from the Post Office to remove any association with the institutions of the Poor Law.

However, Lloyd George did not reject the assumptions of the Poor Law completely. As mentioned above, eligibility to the pension was determined by means and character tests, which simply continued the Victorian distinction between the ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ poor. For Beveridge, means-testing carried the same stigma as the Poor Law. He hoped that the insurance model would ensure that the state pension would not carry the disgrace of charity, since it was dependent on a work record. Pensioners would get out what they had paid in during their careers.

Beveridge proposed that the pension scheme would be fully funded: NICs would build up a National Insurance Fund, which would be invested in government securities and used to finance all liabilities, including pension benefits. The amount each cohort of pensioners received upon retirement would be determined by the amount they paid in, plus interest from investment. This system required a large reserve fund, and to allow for the fund to accumulate, Beveridge included a twenty-year phasing-in period in his calculations.

The phase-in period had solid financial groundings, though was scarcely practical politically. Beveridge’s scheme made no provision for those who were already old when the scheme was enacted, which included individuals who had suffered through the Great Depression and contributed to the war effort. Despite warnings from the Treasury to the contrary, Labour decided to pay full pensions much sooner than Beveridge had envisaged.

Labour’s decision severely weakened the finances of the new state pension, which was now unfunded and pay-as-you-go (PAYG). In a PAYG scheme, a worker’s contributions do not build up a fund out of which their pension will be paid. Instead of accumulating with interest, contributions are used to pay current liabilities.

Importantly, contribution levels must be set relative to what is needed to fund the pensions of current pensioners, rather than the contributing cohorts’ own future benefits. The working generations fund the retirement of their elders, on the condition that later generations do the same. As such, PAYG makes questions of intergenerational justice unavoidable.

PAYG also shapes political incentives. Under a funded scheme, there is no general incentive for a generation to vote for a higher rate of pension accrual, since they would be the ones who will suffer from the increased cost. In an unfunded scheme, this is not true: pensioners will naturally desire greater pension benefits, but are exempt from the extra costs that this would pose. As such, larger generations are able to use their electoral clout to increase pension benefits when they have stopped making NICs. As we shall see, this is exactly what happened with the boomers.

Labour’s decision, then, made the BSP more vulnerable to the demographic pressures of an ageing society. As fertility declines, each subsequent generation will be smaller than the previous one. Under a PAYG scheme, these future generations face an increased per capita burden, since they are smaller than the older generation whose retirement they must fund. In a funded scheme, the cost of the state pension is borne by the generation that would receive it — larger generations would contribute more over their working life, smaller generations less, with the per capita cost remaining roughly constant.

The Treasury was concerned that the shortening of the phase-in period would be ruinous to the long-term financing of the National Insurance Fund, so secured two key concessions. Firstly, pensions would be set below subsistence, about a third less than Beveridge anticipated. Whilst the 1925 pension was deliberately set below subsistence level so as not to discourage people from saving for retirement, Beveridge had hoped that subsistence level pensions would do away with means-testing completely. The Treasury’s decision meant that a National Assistance Board had to be established to provide supplementary support to the poorest pensioners. With the maintenance of means-testing, Beveridge’s pension failed on its own terms.

The second concession the Treasury secured was an agreement that the level of the state pension would not be indexed to rise in line with inflation. Although the Treasury would begrudgingly allow occasional and ad hoc increases throughout the fifties and sixties, the steadily rising prices of the post-war economy eroded the real value of the new pension. Each rise was conceded with great reluctance by the Treasury, which was all too aware of the looming deficit in the National Insurance Fund as a consequence of the decision to abandon Beveridge’s favoured phase-in period to full pension rights.

Due to these concessions, the influence of Beveridge on the BSP was more limited than is often assumed. Instead, it is more accurate to view the BSP as a simple expansion of Chamberlain’s pension as part of the post-war universalisation of National Insurance, created more through accident than far-sighted policy design.

This, more or less, would create the established limits for pension provision for all governments until New Labour. Importantly, it was accepted that the pension would remain below subsistence level, that pensioners had a substantial responsibility to save for their own retirement, and that means-tested benefits would be used as the primary tool to reduce pensioner poverty.

The Blairite Reaction

It will be obvious that the state pension no longer follows the model of Attlee and his successors. The infamous Triple Lock requires that the state pension increases by the highest of average earnings, inflation, or 2.5 percent, with the explicit aim of increasing the state pension to subsistence level. This is a radical departure from the initial ambition of the BSP, which accepted a sub-subsistence pension.

However, this departure did not occur under the Conservatives, but rather under New Labour. Since 1980, the Treasury had been required to uprate the pension at least by inflation. Whilst New Labour kept the price-indexation, it favoured a discretionary policy of uprating the pension by 2.5 percent, if inflation was lower. A discretionary policy was chosen simply because Brown feared that a statutory requirement would reduce Treasury control. As Prime Minister, he would have no problem with offering to use legislation to link pension benefits with earnings in the Labour Party’s Manifesto for the 2010 General Election.

Despite the seemingly genuine denials of many pensioners, this increase in the state pension was paid for by current workers due to the unfunded nature of the National Insurance Fund. Specifically, the steepening in pension accrual was paid for through a National Insurance hike, a regressive tax that is paid only by the working population (unlike income tax).

Significantly, New Labour would further move away from the established model of pension provision by de-emphasising the role of means-tested benefits in combatting pensioner poverty. A series of universal benefits only eligible for the elderly were introduced: free bus passes, free TV licenses, and a generous winter fuel allowance. Since Cold Weather Payments — a separate, little-known benefit — are paid out to all benefit recipients, including those on Pension Credit, when temperatures are below freezing for seven consecutive days, the Winter Fuel Allowance is completely superfluous to helping pensioners get through cold winters. Despite its name, the allowance is simply a universal cash-in-hand benefit to pensioners, completely independent of heating needs, climate, or actual fuel consumption.

The motivations for these policy changes are easy enough to infer. ‘Pensioner poverty’ had risen in the 1990s, with an estimated 2.7 million pensioners living in (relative) poverty in 1997, and, in the face of the immensely beneficial economic conditions it inherited, New Labour felt that it could just throw money at the problem. No matter that affluent pensioners would benefit from the free TV licenses, or that any increases in the state pension would overwhelmingly go to those above the poverty line — New Labour could simply not think of a better use of government spending.

Needless to say, this was not a pragmatic response. It would have been much more cost-effective to ameliorate ‘pensioner poverty’ through targeted means-tested benefits. And in any case, many pensioners benefit from private pensions, both personal and occupational. Indeed, as a result of New Labour’s (very sensible) policy of requiring firms to ‘auto-enrol’ their employees in occupational schemes, coverage of the latter is nearly universal. Although there will necessarily be a policy lag as workers build up their pension, with all workers having a workplace pension ‘auto-enrolment’ could allow for the state pension to be scaled back, with most of the funding for retirement taken on by the private sector. Since occupational schemes also receive extensive tax relief, a subsidy which costs the exchequer £35 billion every year, ‘auto-enrolment’ is an expensive policy, making the increased spending on the state pension all the more egregious.

Nor was New Labour’s pension policy motivated by Beveridge's principled (albeit mistaken) opposition to means-testing. Instead, it was motivated by a bovine moralism, a feeling that pensioners were deserving, and that the state had money to spare, absent of any notion of scarcity or opportunity cost. The reduction of pensioner poverty between 1997 and 2010 is frequently referenced in Gordon Brown’s autobiography, and is clearly one of his proudest achievements in office. (Pensions receive scant mention in Blair’s oddly gnomic memoir — indeed, fewer than thirty pages are devoted to domestic policy.)

This tendency can be seen in Pension Credit, the means-tested benefit introduced by New Labour in 2003. Previously, a Minimum Income Guarantee had topped up the income of poor pensioners to subsistence level. Fearing that the guarantee disincentivised pensioners just above the minimum income level to save, Brown established Pension Credit, which effectively rewards low-income pensioners for saving. Typical of Brown, it was an elegant and ‘wonkish’ solution, with just one flaw: it was incredibly expensive, involving spending on pensioners who were, necessarily, already above the poverty line. Indeed, Brown’s policy likely failed on his own terms, as the effect of the policy was to draw more people into means-testing, extending the extent of disincentives.

This point is worth emphasising. The generally favourable macroeconomic conditions at the start of the millennium - the growth of the City, the end of the Cold War, and most notably, the North Sea oil boom - predisposed whatever government was in power in the early-2000s to huge amounts of spending. A more far-sighted government would have used the windfall from North Sea oil to invest, to reduce the national debt, or even to establish a sovereign wealth fund, à la Norway. An even more farsighted government would have gone some way in dismantling the welfare state. Instead, New Labour was marked by a poverty of ambition. Even basic spending on infrastructure was too much: Brown could think of no better use for taxpayers’ money than wasting it all on the elderly.

It is with these policies that we first see the social contract in Britain being decisively tilted away from the interests of the young. Instead of making the investments that would make Britain a better place for future generations, such as building new reservoirs, Brown focused on increasing the disposable income of already affluent pensioners. His reforms were successful: adjusted for housing costs and the costs of children, the average incomes of pensioner households rose above the average incomes of the rest of the population in 2011, just one year after he left office. Any policy which priorities current consumption — especially the current consumption of pensioners — over long-term investment is necessarily anti-youth.

Continuity under the Coalition

By 2008, the Magic Money Tree had wilted. The Con-Dem Coalition was elected with a mandate to cut government spending, on the tail of the latent middle-class demagoguery of the 2000s. Young people bore the brunt of this austerity: tuition fees were tripled, and the cuts to state spending predominantly affected working families. However, there was no serious consideration of means-testing or cutting the benefits enjoyed by the elderly, or scaling back the increases in the state pension.

Instead, politicians relentlessly discussed how boomers deserved to be rewarded for the sacrifices they had ostensibly made, despite receiving far more from the state during their lifetimes than they have ever contributed through tax. Despite the calls for fiscal pragmatism, of necessary sacrifices, of an end to the ‘age of irresponsibility’, the elderly were not called on to take up their fair share of the pain. Whilst many groups received state patronage from New Labour, pensioners are virtually unique in being exempted from austerity. Again, this policy is not uniquely Conservative. In the Fiscal Responsibility Act 2010, Brown set out his planned tax rises for when the recovery was secured. These plans made clear — for seemingly no good reason — that no pensioner would have paid more tax. (This act would be repealed upon Brown’s removal from office).

Indeed, the Coalition would only exacerbate the transfer of income from the young to the old through the introduction of the Triple Lock in 2011. It is easy to claim that this was motivated by purely electoral reasons, an offering of red meat to the Tory voting bloc; the ‘grey vote’. There is some truth in this, but it should not be over-emphasised.

Due to the metaphor of an insurance fund, it has become clear that many boomers have a misplaced sense of entitlement over their state benefits, believing that such benefits had been fairly earned over a lifetime of paying in, and so would react strongly against a political party that promised to cut them back. As we have seen, this metaphor is mistaken: under a PAYG scheme, the pension is funded entirely through current contributions made by the workforce. Although it seems that Brown had introduced benefits for the elderly for genuine moral reasons, they have remained in place since, due to this sense of entitlement, no party can ever choose to cut benefits to the elderly without severe electoral backlash.

After New Labour’s reforms, all major parties in the 2010 election felt compelled to promise to re-link the state pension with earnings. In fact, the Triple Lock was not found in 2010 Conservative Manifesto, which simply promised a Double Lock, linking the pension to earnings and inflation (with no 2.5 percent minimum guaranteed increase). Instead, the idea came from the Liberal Democrat manifesto, and it was a Liberal Democrat, Steve Webb, who would introduce the Triple Lock as Minister for Pensions in the Coalition Government.

By contrast, cuts to benefits for people of working age would come easily to the Conservative Party, as caricatures of the swollen ‘chav’ class filled the popular imagination of the 2000s. The image of the pensioner shivering in a flat, unable to afford heating, would deter any attempts to promote fiscal prudence.

The consequence is that today, whilst the young receive virtually nothing from the state, and pay the highest tax burden since the war, the elderly enjoy decadent lives gossiping in National Trust cafés. This arrangement is supported by all major parties, and all elements of the British state. The removal of the Conservative Party from office will not change a thing.

This article was written by Lucien Chardon, a Pimlico Journal contributor. Have a pitch? Send it to pimlicojournal@substack.com.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing. If you are already subscribed, why not upgrade to a paid subscription?